An overlooked impact of corporate mergers has been their adverse impact on the gender gap. Under the Consumer Welfare Standard, disparate impact on women and minorities is deemed irrelevant for antitrust policy. This deficiency merely reveals how the Consumer Welfare Standard illegitimately forces policymakers to ignore important features of social welfare in the interest of the merging parties. Merging parties contend that the severe layoffs that often accompany mergers as “efficiencies.” Quite the contrary, these layoffs cause human suffering and social dislocation.

Merger-related job cuts tend to target lower-level positions because they tend to be less specialized in nature and have the most employees. Historically, women and minorities have been over-represented in lower-level positions and under-represented in the highest-wage workforce. According to the Current Population Survey, women comprise 58 percent of the low-wage workforce, and women represent 69 percent of the lowest-wage workforce, referring to those occupations that typically pay less than $10 per hour.

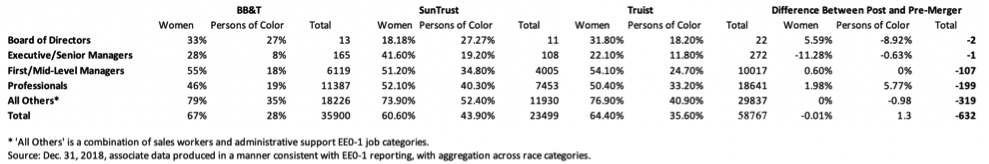

Consider the recent merger of the two banks BB&T and SunTrust. Using the Corporate Social Responsibility Reports from BB&T and SunTrust pre- and post-merger, I estimate that the gender composition across executive and senior managers, originally 28 percent and 42 percent for BB&T and SunTrust, respectively, was reduced to 22 percent post-merger. The antitrust status quo’s inability to address the gender difference, which produces such evident injury to female and minority labor, highlights the basic flaws of utilizing the Consumer Welfare Standard as the only compass to investigate and restrain anticompetitive activity.

Background on the Merger

On February 7, 2019, the boards of both BB&T and SunTrust announced the unanimous approvals to combine in merger of equals. Following discussion, the shareholders approved the merger of equals agreement on July 30, 2019. The parties contended that the merger was needed because of a changing financial landscape, which required increased scale and efficiency in the face of competition from larger banks. The combined entity was expected to benefit from cost savings and synergies (i.e., layoffs), as well as a broader range of products and services for customers.

The merger involved large banks. A Congressional Research Service examination of S&P Global Intelligence data reveals that, since 2010, in 88 percent of bank acquisitions, the acquired bank had assets of less than $1 billion, while in just one percent of acquisitions, the acquired bank had assets exceeding $10 billion. The BB&T-SunTrust merger is a clear outlier: SunTrust’s $215.5 billion in assets surpasses the second largest post-crisis purchase by more than double. Although it was one of the largest mergers in banking history, neither the Federal Reserve Board nor the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation challenged the merger. The Department of Justice ordered the divestiture of approximately $2.3 billion in deposits across seven local markets. While this divestiture ensured that banking consumers in Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia had continued access to competitively priced banking products, including small business loans, none of the federal agencies tasked with reviewing the merger addressed concerns of loss of diversity among the company or the loss of jobs due to said merger.

On December 6, 2019, the merger was officially consummated, and the company was renamed Truist Bank. The merger resulted in a merged corporation with a net value of $66 billion, and assets exceeding $400 billion. It also included around $330 billion in savings from over 10 million American families. The merged corporation is currently the sixth biggest bank in the United States, only preceded by JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo & Co, Citigroup, and U.S. Bancorp.

The Adverse Impact on Labor and on Diversity

The Corporate Social Responsibility forms filed by each company before and after the mergers raise several concerns regarding the loss of diversity among women and persons of color after the merger. In 2018, BB&T had 35,900 workers, while SunTrust had 23,499 workers. Before the merger, the two firms had a combined total of 59,399 employees. After the merger, Truist had a total of 58,767 employees. The workforce was thus reduced by 632 employees. Additionally, in 2018, BB&T had 67 percent women employees, and SunTrust had 61 percent women employees. Thus, the overall percentage of women employees in total between the two companies as a weighted average was 65.1 percent. In comparison, after the merger the percentage of women employees was reduced to 64.4 percent. The number of women in total between the companies decreased from 38,669 before the merger to 37,846 after the merger, for a reduction of 823. This means that the reduction in total workforce can be largely accounted for by the reduction in women employed. In fact, some women were replaced with men after the merger. Overall, we notice reductions of women employed in several positions, including executive and senior managers, sales workers, and administrative support.

The table below highlights the gender and minority distribution pre- and post-merger for the fiscal years 2018 and 2019.

According to these data, we find that there was a loss of diversity, expressed via the Persons of Color column in the Difference Between Post- and Pre-Merger section, among the Board of Directors, Executive and Senior Managers, as well as sales workers and administrative support. The total number of persons of color in the sales workers and administrative support category decreased by 427, using the same calculation method as for women.

These data also reveal that the biggest layoffs occur at lower-level positions such as sales workers, administrative support, and professionals. Only three individuals were laid off from the Board of Directors and Executive and Senior managers positions following the merger, while more than 500 individuals from the professionals, sales and administrative support categories were fired from their positions.

The harsh reality workers face when firms decide to merge goes against the main tenants proposed by welfare economics, which promotes policies that improve human well-being regardless of their race, gender, or ethnicity. But under the Consumer Welfare Standard, these harmful outcomes are deemed irrelevant. Even when monopsony is taken into account during a merger review, the impact to marginalized groups is often ignored. In addition, concentration can worsen diversity across firms and hinder women from climbing the professional ladder. In such situations, an emphasis on consumer welfare tips the balance in favor of the (white male) majority and against minority protected class status.

We need a merger standard that accounts for the impact of mergers on diversity and labor mobility for women. Obviously, antitrust enforcement is only one tool, but an important one. Output is not the only important social value and is far from a comprehensive measure of social welfare. In a political environment where women and persons of color are fighting for their rights, why has antitrust decided to turn a blind eye and favor the white male majority?

Laura Beltran is a Ph.D. student in the economics department at the University of Utah.