“Their goal is simply to mislead, bewilder, confound, and delay and delay and delay until once again we lose our way, and fail to throw off the leash the monopolists have fastened on our neck.” – Barry Lynn

Today, the name Draper is associated with either a fictional adman or a successful real-life venture capital dynasty.

Among the latter, the late Bill Draper was a widely respected early investor in Skype, OpenTable, and other top-tier startups. Less remembered now is the role of the family patriarch—Bill’s father, General William Henry Draper, Junior—in shaping the course of history in postwar Germany and Japan. Well before founding Silicon Valley’s first venture capital firm in 1959, the ür-Draper had made a name for himself in other powerful circles. A graduate of New York University with both a bachelor’s and a master’s in economics, Draper’s early career alternated between stints in investment banking and military service. During World War II, his experience spanned the gamut from developing military procurement policies to commanding an infantry. Socially savvy and obsessively hard-working, Draper was tapped to lead the “economic side of the occupation,” known as the Economics Division, well before Germany officially surrendered in May 1945.

The structure of the military government was cobbled together that summer and fall. Meanwhile, Washington hammered out the principles of occupation policy. Because Germany had surrendered unconditionally, the Allies had “supreme authority” to govern and reform their respective zones. Despite sharp rifts between U.S. agencies about whether Germany deserved a “soft” or a “hard” peace, some goals remained consistent after FDR’s death in April 1945. Notably, there was consensus that Germany’s political and economic systems would both have to be reformed to prevent war and promote democracy.

President Truman personally embraced such principles, which were spelled out in an order from the Joint Chiefs of Staff dictating the mission of the military governor, as well as in the August 1945 Potsdam Agreement between the Allies. The latter document instructed that “[a]t the earliest practicable date, the German economy shall be decentralized for the purpose of eliminating the present excessive concentration of economic power as exemplified in particular by cartels, syndicates, trusts and other monopolistic arrangements.” This policy was undergirded by years of Congressional hearings on how German industry had assisted Hitler’s consolidation of power and path to war.

So how did Draper approach building his Economics Division in light of these mandates? He entrusted an executive from (then monopoly) AT&T to hire men from their network of New York bankers and big business executives. An ominous start, running counter to the antimonopoly mission. There does not appear to have been any effort to recruit staff with more diverse business experience. Draper himself was still technically on leave from Dillon, Read, & Company—an investment bank that, in the decades after World War I, had underwritten over $100 million in German industrial bonds. Those bonds had enabled a German steel firm to buy out its competitors to become the largest steel combine in Germany—and then, the ringmaster of an international cartel.

When the military government’s organizational chart was finalized in the fall of 1945, the Economics Division had swallowed up several other sister proto-divisions, including the group that was investigating cartels and monopolies. This essentially inverted the structure of U.S. domestic enforcement: it was as if economists ran the Federal Trade Commission. Draper later denied engineering this chain of command, which indeed may have been prompted by other factors, including the inconvenient tendency of early decentralization leaders to make press leaks about the military government’s failure to remove some prominent Nazis from positions of power. And at first, Draper was not focused on what the group was doing—he initially viewed their work as tackling “just one of a great many problems.”

Archival footage of the early days

After Senate scrutiny jump-started recruitment of trustbusters en masse, the consequences of depriving the group of Division status became more apparent. The longest-serving leader of the “Decartelization Branch,” James Stewart Martin, had spent much of the war in an “economic warfare” unit investigating warmongering German firms. His team quickly dove into expanding this research and developing legal cases that would be ready to launch once the military government enacted the equivalent of an antitrust law.

Draper believed in bright line rules when it came to cartel agreements: they “should be eliminated, made illegal and prohibited.” Military government eventually passed a law which announced that participation in any international cartel “is hereby declared illegal and is prohibited,” and a year later issued regulations requiring firms to send “notices of termination” informing counterparties that cartel terms were illegal. But Draper viewed “deconcentration” (breaking up combines) differently. He later proclaimed agreement with the general policy, but carefully qualified his statements with loose caveats about not “breaking down the economic situation.” According to members of the Decartelization Branch, Draper and his men thought deconcentration would threaten Germany’s ability to ramp up production enough to sustain itself through exports—even though staffers repeatedly explained that deconcentration would increase output. (The Division’s incessant questioning of the premises of the official U.S. policy may not have been driven by corruption, but also does not appear to have been grounded in evidence, just ideological instincts borne from their professional circles.)

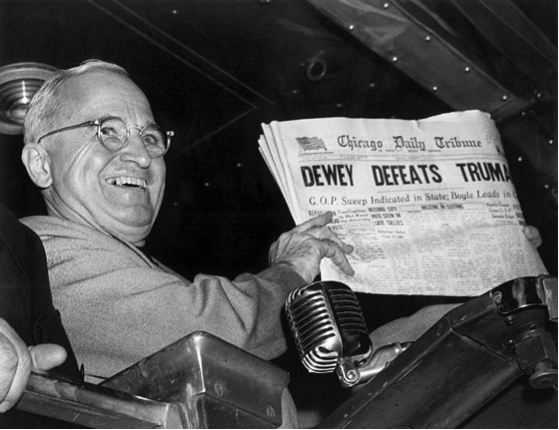

Draper and his men increasingly wielded their veto power to thwart deconcentration efforts. According to Martin, Draper personally teamed up with an intransigent counterpart on the British side to undermine the official U.S. position, successfully delaying negotiation of the law for a year and a half and ultimately weakening the final product. Draper allegedly insisted that accused German firms should be given procedural rights that exceeded those given to domestic companies under U.S. antitrust law—an extraordinary position to take in the context of a hyper-concentrated economy lead by firms that had proactively plotted how they would commandeer rivals in conquered nations. (The timeline allotted for objections and appeals would, coincidentally, postpone final adjudication until after the next U.S. Presidential election, when members of the Economics Division might expect headlines to read “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN.”).

How that gamble turned out (hint: man on left is not Dewey)

There are rarely controls in public policy, but it is telling that the successes in decentralizing Germany’s economy occurred in areas beyond Draper’s veto power—that is, outside of the Decartelization Branch. One signature accomplishment of military government was breaking up the notorious chemical combine I.G. Farben. The United States had captured Farben’s seven-story headquarters in April 1945, and the deputy military governor personally focused on ensuring that a law authorizing the seizure and dissolution of Farben was enacted by all of the Allies by the end of that year. Draper seems to have essentially regarded Farben as the spoils of war, acknowledging that policy considerations other than any potential impact on production or German recovery took precedence in that decision. In any event, the officers in charge of overseeing Farben’s break up reported directly to the military governor, not to Draper. Although Farben was not dispersed to the extent originally envisioned, the military government followed through on reversing the merger that had cemented Farben’s monopoly by spinning off three large successors and a dozen smaller businesses. Another telling accomplishment was the reorganization of the banks into a Federal Reserve-like system. That was handled by the Finance Division, which had co-equal status with Draper’s Economics Division.

Farben and the banks were undoubtedly among the most important targets for decentralizing Germany’s economy, but were likely not the only worthy targets. Wartime investigations concluded that fewer than 100 men controlled over two-thirds of Germany’s industrial system by sitting on the boards of Germany’s Big Six Banks along with 70 industrial combines and holding companies. Although some major industries, such as steel and coal, were located in the British zone, over two dozen firms were based in the U.S. zone. The failure of the military government to launch any actions against any other combines after two years of occupation suggests that something other than good faith disagreements about particular procedures or particular companies was afoot.

There is much, much more to this story: a “factfinding” mission by U.S. industrialists, a cameo by ex-President Herbert Hoover, an untimely marriage, lies, press leaks, Congressional hearings, an internal Army investigation, righteous resignations, early retirements, and more. Not to mention that time Draper swooped into postwar Japan to copy-paste his preferred economic prescriptions over General MacArthur’s reform program there.

Of course, it would be a stretch to conclude that the Decartelization Branch failed to implement a robust antimonopoly program because of one man alone. Others have suggested that even an unhobbled program would have been doomed sooner or later by bickering Allies, changing control of Congress, and the beginning of the Cold War two years into the occupation. Or, perhaps, by the inherent irony of a centralized military tasked with decentralizing a society.

Yet these explanations divert attention from the key ingredients of the pivotal “first 100 days” of any endeavor: institutional structure and selection of mission-aligned leadership. Different choices at that crucial stage might have yielded some tangible early successes and built momentum that could have weathered later headwinds. Taking this possibility seriously underscores why, in modern times, President Biden’s establishment of the competition council and appointment of “Wu, Khan, and Kanter” were so essential—and why ongoing missed opportunities in the administration are so troubling. Elevating amoral excellence and reputed raw managerial ability over other leadership qualifications has consequences. The story of the Decartelization Branch also provides deeper context for understanding how trustbusters approached their work upon returning to the Department of Justice, and for the political will that drove adoption of the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950.

The saga of the Decartelization Branch will be explored in detail in a forthcoming Substack series. This is, for the most part, not a new story, but it is apparently not well-known in antitrust circles; some of the most extensive accounts were written by historians who came across the saga in the course of researching bigger questions, such as the genesis of the Cold War and the rise and fall of international cartels. Perhaps most importantly, the series will be accompanied by new scans of primary sources, to facilitate renewed scholarship into this era.

Laurel Kilgour is a startup attorney in private practice, and also teaches policy courses. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the author’s employers or clients. This is not legal advice about any particular legal situation. To the extent any states might consider this attorney advertising, those states sure have some weird and counterintuitive definitions of attorney advertising.