It’s always better to be a monopolist. “Ruinous competition” is a drag on a company’s profits, particularly when slothful incumbents are forced to compete on the merits. In the case of banks, competition on the merits means increasing rates on deposits for customers with sizeable savings or decreasing overdraft fees for customers with limited funds.

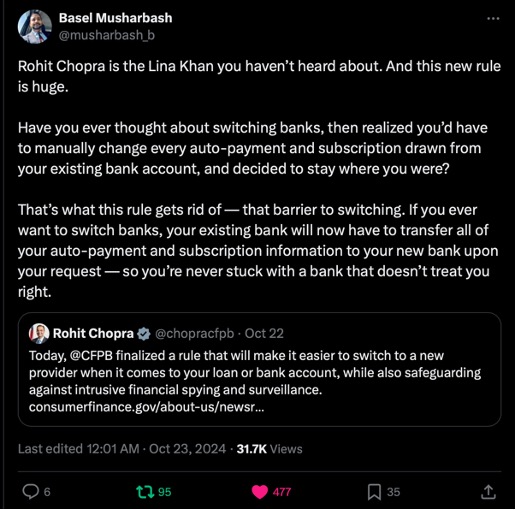

Last week, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finalized a rule that requires financial institutions, credit card issuers, and other financial providers to unlock a customer’s personal financial data—including her transaction history—and transfer it to another provider at the consumer’s request for free. It marks the CFPB’s attempt to activate dormant legal authority of Section 1033 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act. Officially dubbed the “Personal Financial Data Rights” rule, or more casually the “Open Banking” rule, the measure was greeted by those in the budding anti-monopolist movement with glee.

Indeed, FTC Chair Lina Khan, the ultimate champion of competition, tweeted an endorsement of the CFPB’s new rule.

But it wasn’t all rave reviews. The Open Banking rule was also greeted by a swift lawsuit from the Bank Policy Institute (BPI), alleging that the bureau exceeded its statutory authority. The lawsuit also claims the rule risks the “safety and soundness” of the banking system by limiting banks’ discretion to deny upstart banks access to transaction histories. Based on its website, BPI’s membership includes JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Barclays, or what I will call the “incumbent banks.” And JP Morgan’s Jaime Dimon is the Chairman of BPI. Why are the incumbent banks so angry about being compelled to share these transaction histories with upstarts, when such data are arguably the property of the banks’ clients in the first place?

When I first heard about the CFPB’s new rule, I didn’t understand why I needed a regulatory intervention to play one bank off another. For example, after being offered a high CD rate by a scrappy bank, I asked my stodgy bank to match it, only to be ignored by my stodgy bank; I proceeded to write a check from the stodgy bank to the scrappier rival. But having studied the issue, I now understand the particular market failure that the rule seeks to address.

The Rule Would Induce More Aggressive Offers by Upstart Banks

When an upstart bank seeks to pick off a customer from an incumbent bank, the upstart would prefer to extend the most aggressive offer possible, as an inducement to overcome any switching costs that customer might incur. (Fun fact: When interest rates were regulated and interest on checking accounts was banned, banks used to compete by offering toasters to customers at rival banks!) Today’s competitive offer by a rival bank might include a host of ancillary services or “cross-sales” alongside a checking account, such as a credit card, a loan, a line of credit, and payment services. The terms of such offers are governed by the customer’s creditworthiness.

And that’s the catch—the incumbent bank and only the incumbent bank has access to the customer’s transaction history, which includes nuggets like your history of maintaining a balance, overdraft tendencies, and relative timing of payments to income streams. The scrappy upstart, by contrast, is flying blind. And this granular information cannot be obtained through the purchase of a credit report.

Economists refer to such a predicament as “asymmetric information,” and in 2001 three economists even won a Nobel prize for explaining how such asymmetries lead to market failures. In the absence of this information, when formulating its offer, the upstart bank must assume the average tendencies of the borrower based on some peer group, or even worse, it might hedge by assuming the borrower’s creditworthiness is slightly worse than average. As a result, the competitive offer is unnecessary weaker than it could be, and too many customers are sticking with their stodgy (and stingy) bank.

(A fun digression: Some employers inject provisions into a worker’s employment contract that create similar frictions to substitution, which relaxes competitive pressure on wages. You’ve likely heard of a non-compete, which is the ultimate friction. But you may not have heard of a “right-to-match” provision, which gives the incumbent employer a right to match any outside offer from a rival employer. Because the rival employer knows of the provision, and because it’s costly for the rival to formulate an offer, most rivals will give up and the employee never enjoys the benefit of competition.)

The purpose of the Open Banking rule is to induce more aggressive offers by upstart banks and thereby overcome the switching costs associated with changing one’s bank. Put differently, it juices the part of the fin-tech community that seeks to assist consumers, which likely explains the narrow opposition to the rule from incumbent players only. Suppose the customer’s switching costs are $100 and the (weakened) offer from an upstart would improve the customer by $90; under those circumstances, the customer stays put. But if the rule can induce more aggressive offers, boosting the customer benefits of switching to (say) $200, the customer moves. Or she now, with a powerful offer in hand, credibly threatens to switch banks and her stodgy bank improves her terms.

The Open Banking Rule Could Generate Billions in Annual Benefits

The economists of the CFPB have tried to value what this enhanced competition might mean for bank customers. At page 525 of the rule, in a section titled “Potential Benefits and Costs to Consumers and Covered Persons,” the economists explain their valuation methodology:

First, those consumers who switch may earn higher interest rates or pay lower fees. To estimate the potential size of this benefit, the CFPB assumes for this analysis that of the approximately $19 trillion 207 in domestic deposits at FDIC- and NCUA-insured institutions, a little under a third ($6 trillion) are interest-bearing deposits held by consumers, as opposed to accounts held by businesses or noninterest-bearing accounts. If, due to the rule, even one percent of consumer deposits were shifted from lower earning deposit accounts to those with interest rates one percentage point (100 basis points) higher, consumers would earn an additional $600 million annually in interest. Similarly, if due to the rule, consumers were able to switch accounts and thereby avoid even one percent of the overdraft and NSF fees they currently pay, they would pay at least $77 million less in fees per year.

Hence, bank customers who switch banks due to more robust competitive offers made possible by the Open Banking rule would benefit by $677 million per year, based on very conservative assumptions about substitution. And this estimate does not include benefits created for those customers who stay put but nevertheless benefit from the mere threat of leaving. The economists explain that competitive reactions by incumbent banks could lead to a doubling of the aforementioned benefits, to the extent that interest rates on deposits of the non-switchers increase by a mere one basis point. Those benefits would be a transfer from incumbent banks to consumers.

Beware of Fraud Arguments

The Open Banking rule requires that a bank make “covered data” available in electronic form to consumers and to certain “authorized third parties” aka the upstart banks. Covered data includes information about transactions, costs, charges, and usage. The rule spells out what an authorized third party must do to get the covered data, as well as what the “data provider” (aka the incumbent bank) must do upon receiving such a request. The data provider will run its normal fraud review process upon receipt of a data request. Indeed, CFPB even included a provision that states when the data provider has a “legitimate risk management concern,” that concern may trump the data sharing rule.

So any claim that the BPI lawsuit is motivated to protect consumers against fraud or to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking system seems farfetched. The more likely motivation for the challenge is that the Open Banking rule will spur competition among banks, and hence put downward pressure on the incumbent banks’ hefty margins. To wit, JP Morgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, has thrived in a rising rate environment, posting record net income figures since 2022. As the CFPB economists estimate, the rule could raise rates on deposits and reduce rates on overdraft fees, cutting into these record margins. In a similar vein, the CFPB’s new rule might spark competition in the nascent payment system market. Some large banks would like to build their own payment systems (think BoA’s Zelle). By compelling the incumbent banks to share their customers’ transaction histories, however, the Open Banking rule reduces the costs for a scrappy entrant to build a competing payment system. If pay-by-bank gets going, it will be a threat to the incumbent banks’ lucrative credit card and debit card interchange fees. And that threat alone provides billions of reasons to sue the CFPB.