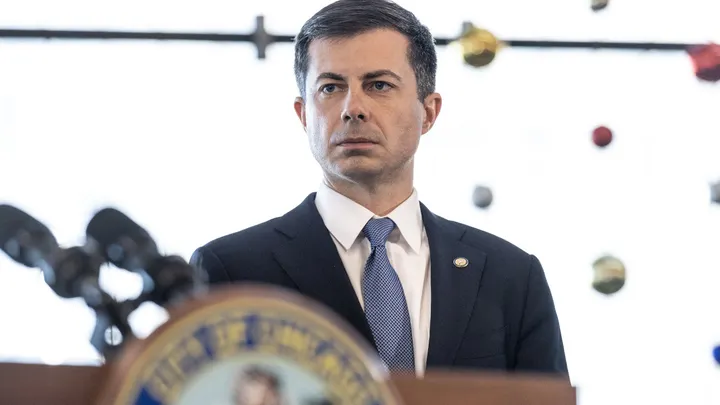

For his first two years as Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg demurred on critical transportation regulation, especially oversight of airlines. Year three has seen a welcome about-face. After letting airlines run amok, Buttigieg and the Department of Transportation (DOT) have finally started taking them to task, including issuing a precedent-shattering fine to Southwest, fighting JetBlue’s proposed merger with Spirit, and—according to news just this morning— scrutinizing unfair and deceptive practices in frequent flier programs. With last week’s announcement of Alaska Airlines’ agreement to purchase Hawaiian Airlines for $1.9 billion, it is imperative that Buttigieg and his DOT keep up the momentum.

Alaska and Hawaiian Airlines are probably the two oddest of the United States’ twelve scheduled passenger airlines, as different as their namesake states are from the lower 48. But the oddity of this union—spurred on by Hawaiian’s financial situation, with Alaska taking on $900 million of Hawaiian’s debt—does nothing to counteract the myriad harms that it would pose to competition.

Although there’s relatively little overlap in flight routes between Alaska and Hawaiian, the geography of the overlap matters. As our friends at The American Prospect have pointed out, Alaska Airlines is Hawaiian’s “main head-to-head competitor from the West Coast to the Hawaiian Islands.”

Alaska flies directly between Hawaii’s four main airports and Anchorage, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Hawaiian has direct flights to and from those same four airports and Seattle, Portland, Sacramento, San Francisco, San Jose, Oakland, Los Angeles, Long Beach, Ontario, and San Diego.

The routes where the two airlines currently compete most, according to route maps from FlightConnections, are the very lucrative West Coast (especially California) to Hawaii flights, as shown below in the table.

Competition on Routes from the West Coast to Hawaii

| Airports | Alaska | Hawaiian | Other Competitors |

| Anchorage | Yes | No | None |

| Seattle* | Yes | Yes | Delta |

| Portland* | Yes | Yes | None |

| Sacramento | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Oakland | No | Yes | Southwest |

| San Francisco* | Yes | Yes | United |

| San Jose* | Yes | Yes | Southwest |

| Los Angeles* | Yes | Yes | American, United, Southwest |

| Long Beach | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Ontario, CA | No | Yes | None |

| San Diego | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Phoenix | No | Yes | American, Southwest |

| Las Vegas | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Salt Lake City | No | Yes | Delta |

| Dallas | No | Yes | American |

| New York | No | Yes (JFK) | Delta (JFK), United (Newark) |

| Boston | No | Yes | None |

As the table shows, five major Hawaiian routes overlap with Alaska Airlines’ offerings: direct flights between Honolulu and Seattle, Portland, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego. This is no coincidence—it was one of the major selling points Alaska Airlines outlined on a call with Wall Street analysts, arguing that the merger would give them half of the $8 billion market in West Coast to Hawaii travel. Four of those routes will also face very little competition from other airlines. Delta is the only other major airline that flies between Seattle and any Hawaii destination, while Southwest is the only other option to fly direct between Hawaii and San Jose or Hawaii and San Diego.

And there is no competing service at all between Hawaii and Portland, where the only options are Alaska and Hawaiian. For this route, the merger is a merger to monopoly. Selling off a landing slot at Portland International Airport would not necessarily restore the loss in actual competition, as the buyer of the slot would be under no obligation to recreate the Portland-Hawaii route.

The merger clearly reduces actual competition on those five overlapping routes. But the merger could also lead to a reduction in potential competition in any route that is currently served by one but was planned to be served by the other. For example, if discovery reveals that Alaska planned to serve the Sacramento to Hawaii route (currently served by Hawaiian) absent the merger, then the merger would eliminate this competition.

But wait! There’s more. Alaska is also a member of the OneWorld Alliance, basically a cabal of international airlines that cooperate to help each other outcompete nonmembers. American Airlines is also a OneWorld member, meaning that Hawaiian will also no longer compete with American once it’s brought under Alaska’s ownership.

The proposed acquisition deal also has implications for the aviation industry more broadly, because concentration tends to beget more concentration. After Delta was allowed to merge with Northwestern, American and United both pursued mergers (with US Airways and Continental, respectively) under the pretense that they needed to get bigger to continue to compete with Delta. Basically, their argument was “you let them do it!”

Similarly, one way to view Alaska’s acquisition of Hawaiian is as a direct response to the proposed JetBlue-Spirit merger. If JetBlue-Spirit goes through, Alaska suddenly loses its spot in the top five biggest US-based airlines. But it gets the spot right back if it buys Hawaiian. This is how midsize carriers go extinct. From a lens that treats continued corporate mergers and lax antitrust enforcement as a given,

Alaska and Hawaiian can argue that their merger will actually keep things more competitive, if you squint the right way. They can claim that together, they will be able to compete more with Southwest’s aggressive expansion into the Hawaii and California markets and help them go toe-to-toe with United and Delta across the US west.

The problem is that this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy—it assumes that companies will continue to merge and grow, such that the only way to make the market more competitive is to create other larger companies. This kind of thinking has led to the miserable state of flying today. Currently, the United States has the fewest domestic airlines since the birth of the aviation industry a century ago. There are only twelve scheduled passenger airlines–with significantly less competition at the route-level–and there hasn’t been significant entry in fourteen years (since Virgin America, which was later bought by Alaska, launched). This is not a recipe for a healthy competitive industry.

Moreover, twelve airlines actually makes the situation sound better than it is. As indicated by the table above, most airports are only served by a fraction of those airlines and antitrust agencies consider the relevant geographic market to be the route. Plus, of those twelve, only four (United, Delta, American, Southwest) have a truly national footprint. Those two factors combined mean that there is very limited competition in all but the largest airports and most flown routes.

In reality, the answer is better antitrust enforcement, which would enable Alaska and Hawaiian to compete with the bigger carriers not by allowing them to merge, but by breaking up the bigger carriers and forcing them to compete. Buttigieg’s DOT and other federal regulatory agencies can use their existing regulatory powers to do so (and brag about it). As airline competition has dwindled, passengers have faced worse conditions, higher prices, and less route diversity. Creating more competition would increase the odds that a company would shock the system by reintroducing larger standard seat sizes, better customer service, lower prices, new routes, or more—and would defend consumers against corporate price gouging, a goal Biden has recently been touting in public appearances.

Last winter, Buttigieg faced the biggest storm of his political career, between Southwest’s absolute collapse during the holidays and an FAA meltdown followed by the East Palestine train debacle. His critics, including us at the Revolving Door Project, pinned a lot of the blame on him and his DOT. Since then, he has responded in a big way. He started by hiring Jen Howard, former chief of staff to FTC Chair Lina Khan, as chief competition officer. They quickly got to work opposing JetBlue’s merger with Spirit Airlines and worked hard to truly bring Southwest to task for their holiday meltdown last year. Just days ago, the DOT announced that it had assessed Southwest a $140 million dollar fine, good for thirty times larger than any prior civil penalty given to an airline, on top of doling out more than $600 million dollars in refunds, rebookings, and other measures to make up for their mistreatment of consumers. Moving forward, the settlement requires Southwest to provide greater remuneration, including paying inconvenienced passengers $75 over and above their reimbursements as compensation for their trouble. Once implemented, this will be an industry-leading compensation policy.

This is exactly the kind of enforcement that we called for nearly a year ago, when we pointed out that the lack of major penalties abetted airline complacency, where carriers did not feel like they needed to follow the law and provide quality service because no one was going to make them. This year has been a wakeup call, both to DOT and to the airline industry about how rigorous oversight can force companies to run a tighter ship—or plane, as the case may be.

Buttigieg took big steps this year, but the Alaska-Hawaiian merger highlights the need for the DOT to remain vigilant. This merger may not be as facially monopolistic as past ones, but it does highlight that airlines are still caught up in their usual games of trying to cut costs and drive up profits by absorbing their competition. Regulators must be equally committed to their roles of catching and punishing wrongdoing, and in the long-term, restructuring firms to create a truly competitive environment that will serve the public interest.

Dylan Gyauch-Lewis is a Senior Researcher at the Revolving Door Project. He leads RDP’s transportation research and helps coordinate the Economic Media Project.