Healthcare in rural America has hit a crisis point. Although the health of people living in rural areas is worse than those living in metropolitan areas, rural populations are deprived of the healthcare services they deserve and need. Rural residents are more likely to be poor and uninsured than urban residents. They are also more likely to suffer from chronic conditions or substance-abuse disorders. Rural communities also experience higher rates of suicide than do communities in urban areas.

For people of color, life in rural America is even harder. Research demonstrates that racial and ethnic minorities in rural areas are less likely to have access to primary care due to prohibitive costs, and they are more likely to die from a severe health condition, such as diabetes or heart disease, compared to their urban counterparts.

Although rural residents in America experience worse health outcomes than urban residents, rural hospitals are closing at a dangerous rate. Rural hospitals experience a severe shortage of nurses and physicians. They also treat more patients who rely on Medicaid and Medicare, or who lack insurance altogether, which means that they offer higher rates of uncompensated care than urban hospitals. For these reasons, hospitals in rural areas are more financially vulnerable than hospitals in metropolitan areas.

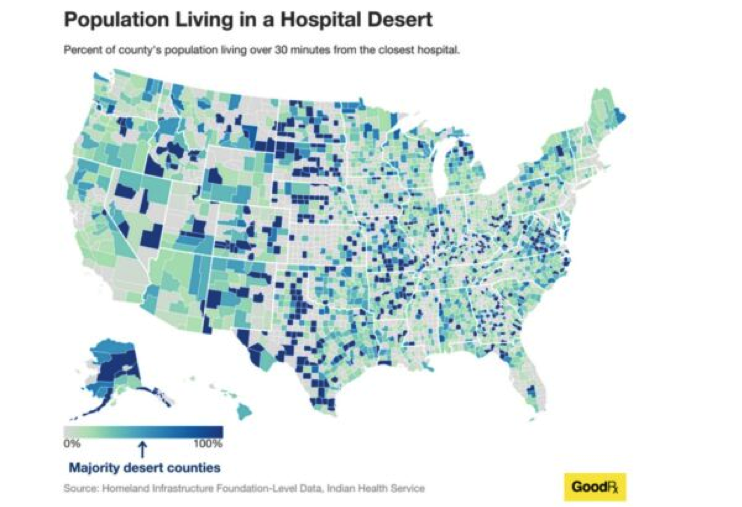

Indeed, recent data show that since 2005, more than 150 rural hospitals have shut their doors and more than 30% of all hospitals in rural areas are at immediate risk of closure. As hospital closures in rural America increase, the areas where residents lack geographic access to hospitals and primary care physicians, or “hospital deserts,” also increase in size and number.

This map is illustrative. It indicates two important things. First, in more than 20% of American counties, residents live in a hospital desert. Second, hospital deserts are primarily located in rural areas.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that hospital deserts reduce access to care for rural residents and exacerbate the rising health disparities in America. When a hospital shuts its doors, rural residents must travel long distances to receive any type of care. Rural residents, however, tend to be more vulnerable to overcoming these obstacles, as some of them do not even have access to a vehicle. For this reason, data show that rural residents often skip doctor appointments, delay necessary care, and stop adhering to their treatment.

Despite the magnitude of the hospital deserts problem and the severe harm they inflict on millions of Americans, public health experts warn that rural communities should not give up. For instance, Medicaid expansion and increased use of telemedicine can increase access to primary care for rural residents and thus can improve the financial stability of rural hospitals. When people lack access to primary care due to lack of coverage, they end up receiving treatment in the hospitals’ emergency departments. For this reason, research shows, rural hospitals offer very high rates of uncompensated care, which ultimately contributes to their closure.

This Antitrust Dimension of Hospital Deserts in Rural America

In a new piece, the Healing Power of Antitrust, I explain that these proposals, albeit fruitful, may fail to cure the problem. The problem of hospital deserts is not only the result of the social and demographic characteristics of rural residents, or the increased level of uncompensated care rural hospitals offer. The hospital deserts that plague underserved areas are also the result of anticompetitive strategies employed by both rural and urban hospitals. These strategies, which include mergers with competitors and non-competes in the labor market, eliminate access to care for rural populations and aggravate the severe shortage of nurses and physicians rural communities experience. In other words, these strategies contribute to hospital deserts in rural America. How did we get here?

In general, hospitals often claim that they need to merge with their competitors to cut their costs and improve their quality. Yet several hospitals often acquire their closest competitors in rural areas just to remove them from the market and increase their market power both in the hospital services and the labor markets.

For this reason, after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals shut down the newly acquired ones. This buy-to-shutter strategy has had a devastating impact on the health of rural communities who desperately need treatment. For instance, data show that each time a rural hospital shuts its doors, the mortality rate of rural residents significantly increases.

Even in cases where hospital mergers do not lead to closures, they still reduce access to care for the most vulnerable Americans—lower income individuals and communities of color. For instance, a recent study indicates that post-merger, only 15% of the acquired hospitals continue to offer acute care services. Other studies show that after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals often move to close essential healthcare services, such as maternal, primary, and surgical care.

When emergency departments in underserved areas shut down, the mental health of rural Americans deteriorates at dangerous rates. For rural Americans who lack coverage, entering a hospital’s emergency department is the only way they can gain access to acute mental healthcare services and substance abuse treatment. Not surprisingly, studies reveal that over the past two decades, the suicide rates for rural Americans have been consistently higher than for urban Americans.

But this is not the only reason why mergers among hospitals in rural areas contribute to the hospital closure crisis. Mergers also allow hospitals to increase their market power in input markets, most notably labor markets, and even attain monopsony power, especially if they operate in rural areas where competition in the hospital industry is limited.

This allows hospitals to suppress the wages of their employees and to offer them employment under unfavorable working conditions and employments terms, including non-competes. This exacerbates the severe shortage of nurses and physicians that rural hospitals are experiencing and, ultimately, contributes to their closures.

Empirical research validates these concerns. A recent study that assessed the relationship between concentration in the hospital industry and the wages of nurses in America reveals that mergers that considerably increased concentration in the hospital market slowed the growth of wages for nurses. Other surveys show that post-merger nurses and physicians experience higher levels of burnout and job dissatisfaction, as well as a heavier workload.

These toxic working conditions become almost inescapable when combined with non-compete clauses. By reducing job mobility, non-competes undermine employers’ incentives to improve the wages and the working conditions of their employees. Sound empirical studies illustrate that these risks are real. For instance, a leading study measuring the relationship between non-competes and wages in the U.S. labor market concludes that decreasing the enforceability of non-competes could increase the average wages for workers by more than 3%. Other surveys reveal that non-competes in the healthcare industry contribute to nurses’ and physicians’ burnout, encouraging them either to leave the market or seek early retirement at increasing rates. This premature exit also exacerbates the shortage of nurses and physicians that is hitting rural America.

Moreover, by eliminating job mobility, non-competes imposed by rural hospitals prevent nurses and physicians from offering their services in competing hospitals in underserved areas, which already struggle to attract workers in the healthcare industry and meet the increased needs of their patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated this problem. When, in the midst of the pandemic, there was a surge of COVID patients, many hospitals lacked the necessary medical staff to meet the demand. For this reason, several hospitals were forced to send patients with severe symptoms back home, leaving them without essential care. This likely contributed to the high mortality rates rural America experienced during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Given these risks, my article asks: Can antitrust law cure the hospital desert problem that harms the health and well-being of rural residents? It makes three proposals.

Proposal 1: Courts should examine all non-competes in the healthcare sector as per se violations of section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits any unreasonable restraints of trade.

Per se illegal agreements are those agreements under antitrust law which are so harmful to competition and consumers that they are unlikely to produce any significant procompetitive benefits. Agreements not condemned as illegal per se are examined under the rule-of-reason legal test, a balancing test that the courts apply to weigh an agreement’s procompetitive benefits against the harm caused to competition. When applying the rule-of-reason test, courts generally follow a “burden-shifting approach.” First, the plaintiff must show the agreement’s main anticompetitive effects. Next, if the plaintiff meets its initial burden, the defendants must show that the agreement under scrutiny also produces some procompetitive benefits. Finally, if the defendant meet its own burden, the plaintiff must show that the defendant’s objectives can be achieved through less restrictive means.

To date, courts have examined all non-compete agreements in labor markets under the rule-of-reason test on the basis that they have the potential to create some procompetitive benefits. For instance, reduced mobility might benefit employers to the extent it allows them to recover the costs of training their workers and reduces the purported “free riding” that may occur if a new employer exploits the investment of the former employer.

Applying the rule-of-reason test in the case of non-competes, especially in the healthcare industry, is a mistake for at least two reasons. First, because hospitals do not appreciably invest in their workers’ education and training, there is little risk of such investment being appropriated. Hence, the claim that non-competes reduce the free riding off non-existent investment is simply unconvincing.

Second, because the rule-of-reason legal test is an extremely complex legal and economic test, the elevated standard of proof naturally benefits well-heeled defendants. This prevents nurses and physicians from challenging unreasonable non-competes, which ultimately encourages their employers to expand their use, even in cases where they lack any legitimate business interest to impose them.

Importantly, the federal agencies tasked with enforcing the antitrust laws, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), have not shut their ears to these concerns. Specifically, the FTC has proposed a new federal regulation that aims to ban all non-compete agreements across America, including those for physicians and nurses. Considering the severe harm non-competes in the healthcare sector cause to nurses, physicians, patients, and ultimately public health, this is a welcome development.

Proposal 2: Antitrust enforcers and the courts should start assessing the impact of hospital mergers on healthcare workers’ wages and working conditions

My article also argues that hospital mergers should be assessed with workers’ welfare at top of mind. Failing to do so will exacerbate the problem of hospital deserts, which so profoundly harms the lives and opportunities for millions of Americans. As noted, mergers allow hospitals to further increase their market power in the labor market. The removal of outside work options allows hospitals to suppress their workers’ wages and to offer employment under unfavorable terms, including non-competes. This encourages nurses and physicians to leave the market at ever increasing rates, which magnifies the severe shortage of nurses and physicians hospitals in rural communities are experiencing and contributes to their closures.

Despite these effects, thus far, whenever the enforcers assessed how a hospital merger may affect competition, they mainly focused on how the merger impacted the prices and the quality of hospital services. So how would the enforcers assess a hospital merger’s impact on labor?

First, enforcers would have to define the relevant labor market in which the anticompetitive effects—namely, suppressed wages and inferior working conditions—are likely to be felt. Second, enforcers would have to assess how the proposed merger may impact the levels of concentration in the labor industry. If the enforcers showed that the proposed merger would substantially increase concentration in the labor market, they would have good reason to stop the merger.

In response to such a showing, the merging hospitals might claim that the merger would create some important procompetitive benefits that may offset any harm to competition caused in the labor market. For instance, the hospitals may claim that the merger would allow hospitals to reduce the cost of labor and, hence, the rates they charge health insurers. This would benefit the purchasers of health insurance services, notably the employers and consumers. But should the courts be convinced by such a claim of offsetting benefits?

Not under the Supreme Court’s ruling in Philadelphia National Bank. There, the Supreme Court made clear that the procompetitive justifications in one market cannot outweigh its anticompetitive effects in another. For this reason, the courts could argue that any benefits the merger may create for one group of consumers—the purchasers of health insurance services—cannot outweigh any losses incurred by another group, the workers in the healthcare industry.

Proposal 3: Antitrust enforcers should accept hospital mergers in rural areas only under specific conditions

My article contends that such mergers should be condoned only under the most stringent of circumstances. Specifically, enforcers should accept mergers in rural areas only under the condition that the merged entity agrees to not shut down facilities or cut essential healthcare services in underserved areas.

Conclusion

Has antitrust law failed workers in the healthcare industry and ultimately public health? Given the concerns expressed above, the answer is unfortunately, yes. By failing to assess the impact of hospital mergers on the wages and the working conditions of employees in the hospital industry, and by examining all non-competes in labor markets under the rule-of-reason legal test, the courts have contributed to the hospital desert problem that disproportionately affects vulnerable Americans. If they fail to confront this crisis, the courts also risk contributing to the racial and health disparities that undermine the moral, social, and economic fabric in America.

Theodosia Stavroulaki is an Assistant Professor of Law at Gonzaga University School of law. Her teaching and research interests include antitrust, health law, and law and inequality. This piece draws on her article “The Healing Power of Antitrust” forthcoming in Northwestern University Law Review 119(4) (2025)

In condemning Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel, many politicians, from John Fetterman to Donald Trump, are ignoring the severe costs of the alternative tie-up with a domestic steel-making rival—the harms to competition in both labor and product markets from the alternative merger with Cleveland-Cliffs (the “alternative merger”). Whatever security concerns might flow from ceding control of a large steel operation to a Japanese company must be assessed against the likely antitrust injury that would be inflicted on domestic workers and steel buyers by combining two direct horizontal competitors in the same geographic market. This basic economic point has been lost in the kerfuffle.

Harms to Labor

The first place to consider competitive injury from the alternative merger is the labor market, in which Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel compete for labor working in mines. If Cleveland-Cliffs (“Cliffs”) had been selected by U.S. Steel, there would only be one steel employer remaining in some geographic markets such as northern Minnesota and Gary, Indiana. This consolidation of buying power would have reduced competition in hiring of steel workers, almost certainly driving down workers’ wages by limiting their mobility.

To wit, Minnesota’s Star Tribune noted that “Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel have long histories on Minnesota’s Iron Range, controlling all six of the area’s taconite operations. Cliffs fully owns three of the six taconite mines, and U.S. Steel owns two.” Ownership of the sixth mine is shared between Cliffs (85%) of U.S. Steel (15%). A Cliffs/U.S. Steel merger also would have made the combined company the sole industry employer in the region surrounding Gary, per the American Prospect. Additional harms from newfound buying power include reduced jobs and greater control over workers who retain their jobs.

The newly revised DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines explain that labor markets are especially vulnerable to mergers, as workers cannot substitute to outside employment options with the same ease as consumers substituting across beverages or ice cream. But the harm to labor here is not merely theoretical: A recent paper by Prager and Schmitt (2021) found that mergers among hospitals had a substantial negative effect on wages for workers whose skills are much more useful in hospitals than elsewhere (e.g., nurses). In contrast, the merger had no discernible effect on wages for workers whose skills are equally useful in other settings (e.g., custodians). A paper I co-authored with Ted Tatos found labor harms from University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s acquisitions of Pennsylvania hospitals. And Microsoft’s recent acquisition of Activision was immediately followed by the swift termination of 1,900 Activision game developers, a fate that was predictable based on the combined firm’s footprint among gaming developers, as well job-switching data between Microsoft and Activision.

This is the type of harm that the U.S. antitrust agencies would almost assuredly investigate under the new antitrust paradigm, which elevates workers’ interests to the same level as consumers’ interests. Indeed, the Department of Justice recently blocked a merger among book publishers under a theory of harm to book authors. Under Lina Khan’s stewardship, the Federal Trade Commission is likely searching for its own labor theory of harm, potentially in the Kroger-Albertsons merger.

And the Nippon acquisition would largely avoid this type of harm, as Nippon does not compete as intensively, compared to Cliffs, against U.S. Steel in the domestic labor market. To be fair, Nippon does have a small American presence: It has investments in several U.S. companies and employs (directly and indirectly) about 4,000 Americans—but far fewer than U.S. Steel (21,000 U.S. based employees) and Cliffs (27,000 U.S. based employees). Importantly, Nippon employs no steelworkers in Minnesota, and its plants in Seymour and Shelbyville, Indiana are roughly a three-hour drive from Gary.

It bears noting that United Steelworkers (USW), the union representing steelworkers, has come out against the Nippon/U.S. Steel merger, alleging that U.S. Steel violated the successorship clause in its basic labor agreements with the USW when it entered the deal with a North American holding company of Nippon. This opposition is not proof, however, that the alternative merger is beneficial to workers, or even more beneficial to workers than the Nippon deal. Recall that the union representing game developers endorsed Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision, which turned out to be pretty rotten for 1,900 former Activision employees. Sometimes union leaders get things wrong with the benefit of hindsight, even when their hearts are in the right place.

Harms to Steel Buyers

Setting aside the labor harms, the alternative merger would result in Cliffs becoming “the last remaining integrated steelmaker in the country.” Mini-mill operators like Nucor and Steel Dynamics do not serve some key segments served by integrated steelmakers, such as the market for selling steel to automakers. In particular, automakers cannot swap out steel made from recycled scrap at mini-mills with stronger and more malleable steel made from steel blast furnaces. According to Bloomberg, a combined Cliffs/U.S. Steel would become the primary supplier of coveted automotive steel.

The prospect of Cliffs acquiring U.S. Steel triggered the automotive trade association, the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, to send a letter to the leadership of the Senate and House subcommittees on antitrust, explaining that a “consolidation of steel production capacity in the U.S. will further increase costs across the industry for both materials and finished vehicles, slow EV adoption by driving up costs for customers, and put domestic automakers at a competitive disadvantage relative to manufacturers using steel from other parts of the world.”

Moreover, a U.S. Steel regulatory filing detailed how antitrust concerns in the output market factored in its decision to reject Cliffs’s bid. U.S. Steel’s proxy noted: “A transaction with [Cliffs] would eliminate the sole new competitor in non-grain-oriented steel production in North America as well as eliminate a competitive threat to [Cliffs’s] incumbent position in the U.S., and put up to 95% of iron ore production in the U.S. under the control of a single company.”

Once again, the lack of any material presence by Nippon in the United States ensures that such consumer harms are largely limited to the Cliffs tie-up. An equity research analyst with New York-based CFRA Research who follows the steel industry noted that Nippon has a “very small footprint currently in North America.”

Balancing Security Concerns Against Competition Harms

Regarding national security concerns from a Nippon-U.S. Steel tie-up, The Economist opined these harms are exaggerated: “A Chinese company shopping for American firms producing cutting-edge technology that could help its country’s armed forces should, and does, set off warning sirens. Nippon’s acquisition should not.” If the concern is control of a domestic steelmaker during wartime, the magazine explained, U.S. Steel’s operations “could be requisitioned from a disobliging foreign owner.” For the purpose of this piece, however, I conservatively assume that the security costs from a Nippon tie-up are economically significant. My point is that there are also significant costs to workers and automakers from choosing a tie-up with Cliffs, and sound policy militates in favor of measuring and then balancing those two costs.

Finally, this perspective is based on the assumption that U.S. Steel must find a buyer to compete effectively. Maintaining the status quo would evade both national security and competition harms implicated by the respective mergers. But if policymakers must choose a buyer, they should consider both the competition harms and the national security implications. Ignoring the competition harms, as some protectionists are inclined to do, makes a mockery of cost-benefit analysis.

The FTC just secured a big win in its IQVIA/Propel case, the agency’s fourth blocked merger in as many weeks. This string of rapid-fire victories quieted a reactionary narrative that the agency is seeking to block too many deals and also should win more of its merger challenges. (“The food here is terrible, and the portions are too small!”) But the case did a lot more than that.

Blocking Anticompetitive Deals Is Good—Feel Free to Celebrate!

First and foremost, this acquisition, based on my read of the public court filings, was almost certainly illegal. Blocking a deal like this is a good thing, and it’s okay to celebrate when good things happen—despite naysayers grumbling about supporters not displaying what they deem the appropriate level of “humility.” Matt Stoller has a lively write-up explaining the stakes of the case. In a nutshell, it’s dangerous for one company to wield too much power over who gets to display which ads to healthcare professionals. Kudos to the FTC caseteam for securing this win.

Judge Ramos Gets It Right

A week ago, the actual opinion explaining Judge Ramos’s decision dropped. It’s a careful, thorough analysis that makes useful statements throughout—and avoids some notorious antitrust pitfalls. Especially thoughtful was his treatment of the unique standard that applies when the FTC asks to temporarily pause a merger pending its in-house administrative proceeding. Federal courts are supposed to play a limited role that leaves the final merits adjudication to the agency. That said, it’s easy for courts to overreach, like Judge Corley’s opinion in Microsoft/Activision that resolved several important conflicts in the evidence—exactly what binding precedent said not to do. This may seem a little wonky, but it’s playing out against the backdrop of a high-stakes war against administrative agencies. So although “Judge Does His Job” isn’t going to make headlines, it’s refreshing to see Judge Ramos’s well-reasoned approach.

The IQVIA decision is also great on market definition, another area where judges sometimes get tripped up. Judge Ramos avoided the trap defendants laid with their argument that all digital advertising purveyors must be included in the same relevant market because they all compete to some extent. That’s not the actual legal question—which asks only about “reasonable” substitutes—and the opinion rightly sidestepped it. We can expect to see similar arguments made by Big Tech companies in future trials, so this holding could be useful to both DOJ and FTC as they go after Meta, Google, and Amazon.

How Does This Decision Fit Into the Broader Project of Reinvigorating Antitrust?

One core goal shared by current agency leadership appears to be making sure that antitrust can play a role in all markets—whether they’re as traditional as cement or as fast-moving as VR fitness apps.

The cornerstone of IQVIA’s defense was that programmatic digital advertising to healthcare professionals is a nascent, fast-moving market, so there’s no need for antitrust enforcement. This has long been page one of the anti-enforcement playbook, as it was in previous FTC merger challenges like Meta/Within. But, in part because the FTC won the motion to dismiss in that case, we have some very recent—and very favorable—law on the books rejecting this ploy.

Sure enough, Judge Ramos’s IQVIA opinion built on that foundation. He cited Meta/Within multiple times to reject these defendants’ similar arguments that market nascency provides an immunity shield against antitrust scrutiny. “While there may be new entrants into the market going forward,” Judge Ramos explained, “that does not necessarily compel the conclusion that current market shares are unreliable.” Instead, the burden is on defendants to prove historical shifts in market shares are so significant that they make current data “unusable for antitrust analysis.” His opinion is clear, and clearly persuasive—DOJ and a group of state AGs already submitted it as supplemental authority in their challenge to JetBlue’s proposed tie-up of Spirit Airlines.

A second goal that appears to be top-of-mind for the new wave of enforcers is putting all of their legal tools back on the table. Here again, the IQVIA win fits into the broader vision for a reinvigorated antitrust enterprise.

Just a few weeks before this decision, the FTC got a groundbreaking Fifth Circuit opinion on its challenge to the Illumina/GRAIL deal. Illumina had argued that the Supreme Court’s vertical-merger liability framework is no longer good law because it’s too old. In other words, the tool had gotten so dusty that high-powered defense attorneys apparently felt comfortable arguing it was no longer usable. That happened in Meta/Within as well: Meta argued both of the FTC’s legal theories involving potential competition were “dead-letter doctrine.” But in both cases, the FTC won on the substance—dusting off three unique anti-merger tools in the process.

IQVIA adds yet another: the “30% threshold” presumption from Philadelphia National Bank. Like Meta and Illumina before it, IQVIA argued strenuously that the legal tool itself was invalid because it had long been out of favor with the political higher-ups at federal agencies. But yet again, the judge rejected that argument out of hand. The 30% presumption is alive and well, vindicating the agencies’ decision to put it back into the 2023 Merger Guidelines.

Stepping back, we’re starting to see connections and cumulative effects. The FTC won a motion to dismiss in Meta/Within, lost on the injunction, but made important case law in the process. IQVIA picked up right where that case left off, and this time, the FTC ran the table.

Positive projects take time. It’s easier to tear down than to build. And both agencies remain woefully under-resourced. But change—real, significant change—is happening. In the short run, it’s impressive that four mergers were blocked in a month. In the long run, it’s important that four anti-merger tools are now back on the table.

John Newman is a professor at the University of Miami School of Law. He previously served as Deputy Director at the FTC’s Bureau of Competition.

For his first two years as Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg demurred on critical transportation regulation, especially oversight of airlines. Year three has seen a welcome about-face. After letting airlines run amok, Buttigieg and the Department of Transportation (DOT) have finally started taking them to task, including issuing a precedent-shattering fine to Southwest, fighting JetBlue’s proposed merger with Spirit, and—according to news just this morning— scrutinizing unfair and deceptive practices in frequent flier programs. With last week’s announcement of Alaska Airlines’ agreement to purchase Hawaiian Airlines for $1.9 billion, it is imperative that Buttigieg and his DOT keep up the momentum.

Alaska and Hawaiian Airlines are probably the two oddest of the United States’ twelve scheduled passenger airlines, as different as their namesake states are from the lower 48. But the oddity of this union—spurred on by Hawaiian’s financial situation, with Alaska taking on $900 million of Hawaiian’s debt—does nothing to counteract the myriad harms that it would pose to competition.

Although there’s relatively little overlap in flight routes between Alaska and Hawaiian, the geography of the overlap matters. As our friends at The American Prospect have pointed out, Alaska Airlines is Hawaiian’s “main head-to-head competitor from the West Coast to the Hawaiian Islands.”

Alaska flies directly between Hawaii’s four main airports and Anchorage, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Hawaiian has direct flights to and from those same four airports and Seattle, Portland, Sacramento, San Francisco, San Jose, Oakland, Los Angeles, Long Beach, Ontario, and San Diego.

The routes where the two airlines currently compete most, according to route maps from FlightConnections, are the very lucrative West Coast (especially California) to Hawaii flights, as shown below in the table.

Competition on Routes from the West Coast to Hawaii

| Airports | Alaska | Hawaiian | Other Competitors |

| Anchorage | Yes | No | None |

| Seattle* | Yes | Yes | Delta |

| Portland* | Yes | Yes | None |

| Sacramento | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Oakland | No | Yes | Southwest |

| San Francisco* | Yes | Yes | United |

| San Jose* | Yes | Yes | Southwest |

| Los Angeles* | Yes | Yes | American, United, Southwest |

| Long Beach | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Ontario, CA | No | Yes | None |

| San Diego | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Phoenix | No | Yes | American, Southwest |

| Las Vegas | No | Yes | Southwest |

| Salt Lake City | No | Yes | Delta |

| Dallas | No | Yes | American |

| New York | No | Yes (JFK) | Delta (JFK), United (Newark) |

| Boston | No | Yes | None |

As the table shows, five major Hawaiian routes overlap with Alaska Airlines’ offerings: direct flights between Honolulu and Seattle, Portland, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego. This is no coincidence—it was one of the major selling points Alaska Airlines outlined on a call with Wall Street analysts, arguing that the merger would give them half of the $8 billion market in West Coast to Hawaii travel. Four of those routes will also face very little competition from other airlines. Delta is the only other major airline that flies between Seattle and any Hawaii destination, while Southwest is the only other option to fly direct between Hawaii and San Jose or Hawaii and San Diego.

And there is no competing service at all between Hawaii and Portland, where the only options are Alaska and Hawaiian. For this route, the merger is a merger to monopoly. Selling off a landing slot at Portland International Airport would not necessarily restore the loss in actual competition, as the buyer of the slot would be under no obligation to recreate the Portland-Hawaii route.

The merger clearly reduces actual competition on those five overlapping routes. But the merger could also lead to a reduction in potential competition in any route that is currently served by one but was planned to be served by the other. For example, if discovery reveals that Alaska planned to serve the Sacramento to Hawaii route (currently served by Hawaiian) absent the merger, then the merger would eliminate this competition.

But wait! There’s more. Alaska is also a member of the OneWorld Alliance, basically a cabal of international airlines that cooperate to help each other outcompete nonmembers. American Airlines is also a OneWorld member, meaning that Hawaiian will also no longer compete with American once it’s brought under Alaska’s ownership.

The proposed acquisition deal also has implications for the aviation industry more broadly, because concentration tends to beget more concentration. After Delta was allowed to merge with Northwestern, American and United both pursued mergers (with US Airways and Continental, respectively) under the pretense that they needed to get bigger to continue to compete with Delta. Basically, their argument was “you let them do it!”

Similarly, one way to view Alaska’s acquisition of Hawaiian is as a direct response to the proposed JetBlue-Spirit merger. If JetBlue-Spirit goes through, Alaska suddenly loses its spot in the top five biggest US-based airlines. But it gets the spot right back if it buys Hawaiian. This is how midsize carriers go extinct. From a lens that treats continued corporate mergers and lax antitrust enforcement as a given,

Alaska and Hawaiian can argue that their merger will actually keep things more competitive, if you squint the right way. They can claim that together, they will be able to compete more with Southwest’s aggressive expansion into the Hawaii and California markets and help them go toe-to-toe with United and Delta across the US west.

The problem is that this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy—it assumes that companies will continue to merge and grow, such that the only way to make the market more competitive is to create other larger companies. This kind of thinking has led to the miserable state of flying today. Currently, the United States has the fewest domestic airlines since the birth of the aviation industry a century ago. There are only twelve scheduled passenger airlines–with significantly less competition at the route-level–and there hasn’t been significant entry in fourteen years (since Virgin America, which was later bought by Alaska, launched). This is not a recipe for a healthy competitive industry.

Moreover, twelve airlines actually makes the situation sound better than it is. As indicated by the table above, most airports are only served by a fraction of those airlines and antitrust agencies consider the relevant geographic market to be the route. Plus, of those twelve, only four (United, Delta, American, Southwest) have a truly national footprint. Those two factors combined mean that there is very limited competition in all but the largest airports and most flown routes.

In reality, the answer is better antitrust enforcement, which would enable Alaska and Hawaiian to compete with the bigger carriers not by allowing them to merge, but by breaking up the bigger carriers and forcing them to compete. Buttigieg’s DOT and other federal regulatory agencies can use their existing regulatory powers to do so (and brag about it). As airline competition has dwindled, passengers have faced worse conditions, higher prices, and less route diversity. Creating more competition would increase the odds that a company would shock the system by reintroducing larger standard seat sizes, better customer service, lower prices, new routes, or more—and would defend consumers against corporate price gouging, a goal Biden has recently been touting in public appearances.

Last winter, Buttigieg faced the biggest storm of his political career, between Southwest’s absolute collapse during the holidays and an FAA meltdown followed by the East Palestine train debacle. His critics, including us at the Revolving Door Project, pinned a lot of the blame on him and his DOT. Since then, he has responded in a big way. He started by hiring Jen Howard, former chief of staff to FTC Chair Lina Khan, as chief competition officer. They quickly got to work opposing JetBlue’s merger with Spirit Airlines and worked hard to truly bring Southwest to task for their holiday meltdown last year. Just days ago, the DOT announced that it had assessed Southwest a $140 million dollar fine, good for thirty times larger than any prior civil penalty given to an airline, on top of doling out more than $600 million dollars in refunds, rebookings, and other measures to make up for their mistreatment of consumers. Moving forward, the settlement requires Southwest to provide greater remuneration, including paying inconvenienced passengers $75 over and above their reimbursements as compensation for their trouble. Once implemented, this will be an industry-leading compensation policy.

This is exactly the kind of enforcement that we called for nearly a year ago, when we pointed out that the lack of major penalties abetted airline complacency, where carriers did not feel like they needed to follow the law and provide quality service because no one was going to make them. This year has been a wakeup call, both to DOT and to the airline industry about how rigorous oversight can force companies to run a tighter ship—or plane, as the case may be.

Buttigieg took big steps this year, but the Alaska-Hawaiian merger highlights the need for the DOT to remain vigilant. This merger may not be as facially monopolistic as past ones, but it does highlight that airlines are still caught up in their usual games of trying to cut costs and drive up profits by absorbing their competition. Regulators must be equally committed to their roles of catching and punishing wrongdoing, and in the long-term, restructuring firms to create a truly competitive environment that will serve the public interest.

Dylan Gyauch-Lewis is a Senior Researcher at the Revolving Door Project. He leads RDP’s transportation research and helps coordinate the Economic Media Project.

Right before Thanksgiving, Josh Sisco wrote that the Federal Trade Commission is investigating whether the $9.6 billion purchase of Subway by private equity firm Roark Capital creates a sandwich shop monopoly, by placing Subway under the same ownership as Jimmy John’s, Arby’s, McAlister’s Deli, and Schlotzky’s. The acquisition would allow Roark to control over 40,000 restaurants nationwide. Senator Elizabeth Warren amped up the attention by tweeting her disapproval of the merger, prompting the phrase “Big Sandwich” to trend on Twitter.

Fun fact: Roark is named for Howard Roark, the protagonist in Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead, which captures the spirit of libertarianism and the anti-antitrust movement. Ayn Rand would shrug off this and presumably any other merger!

It’s a pleasure reading pro-monopoly takes on the acquisition. Jonah Goldberg writes in The Dispatch that sandwich consumers can easily switch, in response to a merger-induced price hike, to other forms of lunch like pizza or salads. (Similar screeds appear here and here.) Jonah probably doesn’t understand the concept, but he’s effectively arguing that the relevant product market when assessing the merger effects includes all lunch products, such that a hypothetical monopoly provider of sandwiches could not profitably raise prices over competitive levels. Of course, if a consumer prefers a sandwich, but is forced to eat a pizza or salad to evade a price hike, her welfare is almost certainly diminished. And even distant substitutes like salads might appear to be closer to sandwiches when sandwiches are priced at monopoly levels.

The Brown Shoe factors permit courts to assess the perspective of industry participants when defining the contours of a market, including the merging parties. Subway’s franchise agreement reveals how the company perceives its competition. The agreement defines a quick service restaurant that would be “competitive” for Subway as being within three miles of one of its restaurants and deriving “more than 20% of its total gross revenue from the sale of any type of sandwiches on any type of bread, including but not limited to sub rolls and other bread rolls, sliced bread, pita bread, flat bread, and wraps.” The agreement explicitly mentions by name Jimmy John’s, McAlister’s Deli and Schlotzky’s as competitors. This evidence supports a narrower market.

Roark’s $9.6 billion purchase of Subway exceeded the next highest bid by $1.35 billion—from TDR Capital and Sycamore Partners at $8.25 billion—an indication that Roark is willing to pay a substantial premium relative to other bidders, perhaps owing to Roark’s existing restaurant holdings. The premium could reflect procompetitive merger synergies, but given what the economic literature has revealed about such purported benefits, the more likely explanation of the premium is that Roark senses an opportunity to exercise newfound market power.

To assess Roark’s footprint in the restaurant business, I downloaded the Nation’s Restaurant News (NRN) database of sales and stores for the top 500 restaurant chains. If one treats all chain restaurants as part of the relevant product market, as Jonah Goldberg prefers, with total sales of $391.2 billion in 2022, then Roark’s pre-merger share of sales (not counting Subway) is 10.8 percent, and its post-merger share of sales is 13.1 percent. These numbers seem small, especially the increment to concentration owing to the merger.

Fortunately, the NRN data has a field for fast-food segment. Both Subway and Jimmy John’s are classified as “LSR Sandwich/Deli,” where LSR stands for limited service restaurants, which don’t offer table service. By comparison, McDonald’s, Panera, and Einstein are classified under “LSR Bakery/Café”. If one limits the data to the LSR Sandwich/Deli segment, total sales in 2022 fall from $391.1 billion to $26.3 billion. Post-merger, Roark would own four of the top six sandwich/deli chains in America. It bears noting that imposing this filter eliminates several of Roark’s largest assets—e.g., Dunkin’ Donuts (LSR Coffee), Sonic (LSR Burger), Buffalo Wild Wings (FSR Sports Bar)—from the analysis.

Restaurant Chains in LSR Sandwich/Deli Sector, 2022

| Chain | Sales (Millions) | Units | Share of Sales |

| Subway* | 9,187.9 | 20,576 | 34.9% |

| Arby’s* | 4,535.3 | 3,415 | 17.2% |

| Jersey Mike’s | 2,697.0 | 2,397 | 10.3% |

| Jimmy John’s* | 2,364.5 | 2,637 | 9.0% |

| Firehouse Subs | 1,186.7 | 1,187 | 4.5% |

| McAlister’s Deli* | 1,000.4 | 524 | 3.8% |

| Charleys Philly Steaks | 619.8 | 642 | 2.4% |

| Portillo’s Hot Dogs | 587.1 | 72 | 2.2% |

| Jason’s Deli | 562.1 | 245 | 2.1% |

| Potbelly | 496.1 | 429 | 1.9% |

| Wienerschnitzel | 397.3 | 321 | 1.5% |

| Schlotzsky’s* | 360.8 | 323 | 1.4% |

| Chicken Salad Chick | 284.1 | 222 | 1.1% |

| Penn Station East Coast | 264.3 | 321 | 1.0% |

| Mr. Hero | 157.9 | 109 | 0.6% |

| American Deli | 153.2 | 204 | 0.6% |

| Which Wich | 131.3 | 226 | 0.5% |

| Capriotti’s | 122.6 | 142 | 0.5% |

| Nathan’s Famous | 119.1 | 272 | 0.5% |

| Port of Subs | 112.9 | 127 | 0.4% |

| Togo’s | 107.7 | 162 | 0.4% |

| Biscuitville | 107.5 | 68 | 0.4% |

| Cheba Hut | 95.0 | 50 | 0.4% |

| Primo Hoagies | 80.4 | 94 | 0.3% |

| Cousins Subs | 80.1 | 93 | 0.3% |

| Ike’s Place | 79.3 | 81 | 0.3% |

| D’Angelo | 75.4 | 83 | 0.3% |

| Dog Haus | 73 | 58 | 0.3% |

| Quiznos Subs | 57.8 | 165 | 0.2% |

| Lenny’s Sub Shop | 56.3 | 62 | 0.2% |

| Sandella’s | 51 | 52 | 0.2% |

| Erbert & Gerbert’s | 47.4 | 75 | 0.2% |

| Goodcents | 47.3 | 66 | 0.2% |

| Total | 26,298.60 | 230,629 | 100.0% |

Source: Nation’s Restaurant News (NRN) database of sales and stores for the top 500 restaurant chains. Note: * Owned by Roark

With this narrower market definition, Roark’s pre-merger share of sales (not counting Subway) is 31.4 percent, and its post-merger share of sales is 66.3 percent. These shares seem large, and the standard measure of concentration—which sums the square of the market shares—goes from 2,359 to 4,554, which would create the inference of anticompetitive effects under the 2010 Merger Guidelines.

One complication to the merger review is that Roark wouldn’t have perfect control of the sandwich pricing by its franchisees. Franchisees often are free to set their own prices, subject to suggestions (and market studies) by the franchise. So while Roark might want (say) a Jimmy John’s franchisee to raise sandwich prices after the merger, that franchisee might not internalize the benefits to Roark of diversion of some its customers to Subway. With enough money at stake, Roark could align its franchisees’ incentives with the parent company, by, for example, creating profit pools based on the profits of all of Roark’s sandwich investments.

Another complication is that Roark does not own 100 percent of its restaurants. Roark is the majority-owner of Inspire Brands. In July 2011, Roark acquired 81.5 percent of Arby’s Restaurant Group. Roark purchased Wendy’s remaining 12.3 percent holding of Inspire Brands in 2018. To the extent Roark’s ownership of any of the assets mentioned above is partial, a modification to the traditional concentration index could be performed, along the lines spelled out by Salop and O’Brien. (For curious readers, they show in how the change in concentration is a function of the market shares of the acquired and acquiring firms plus the fraction of the profits of the acquired firm captured by the acquiring firm, which varies according to different assumption about corporate control.)

When defining markets and assessing merger effects, it is important to recognize that, in many towns, residents will not have access to the fully panoply of options listed in the top 500 chains. (Credit to fellow Sling contributor Basel Musharbash for making this point in a thread.) So even if one were to conclude that the market was larger than LSR Sandwich/Deli chains, it wouldn’t be the case that residents could chose from all such restaurants in the (expanded) relevant market. Put differently, if you live in a town where your only options are Subway, Jimmy John’s, and McDonald’s, the merger could significantly concentrate economic power.

Although this discussion has focused on the harms to consumers, as Brian Callaci points out, the acquisition could allow Roark to exercise buying power vis-à-vis the sandwich shops suppliers. And Helaine Olen explains how the merger could enhance Roark’s power over franchise owners. The DOJ recently blocked a book-publisher merger based on a theory of harm to input providers (publishers), indicating that consumers no longer sit alone atop the antitrust hierarchy.

While it’s too early to condemn the merger, monopoly-loving economists and libertarians who mocked the concept of Big Sandwich should recognize that there are legitimate economic concerns here. It all depends on how you slice the market!

How many times have you heard from an antitrust scholar or practitioner that merely possessing a monopoly does not run afoul of the antitrust laws? That a violation requires the use of a restraint to extend that monopoly into another market, or to preserve the original monopoly to constitute a violation? Here’s a surprise.

Both a plain reading and an in-depth analysis of the text of Section 2 of the Sherman Act demonstrate that this law’s violation does not require anticompetitive conduct, and that it does not have an efficiencies defense. Section 2 of the Sherman Act was designed to impose sanctions on any firm that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize a market. Period. With no exceptions for firms that are efficient or for firms that did not engage in anticompetitive conduct.

This is the conclusion one should reach if one were a judge analyzing the Sherman Act using textualist principles. Like most of the people reading this article I’m not a textualist. But many judges and Supreme Court Justices are, so this method of statutory interpretation must be taken quite seriously today.

To understand how to read the Sherman Act as a textualist, one must first understand the textualist method of statutory interpretation. This essay presents a textualist analysis of Section 2 that is a condensation of a 92-page law review article, titled “The Sherman Act Is a No-Fault Monopolization Statute: A Textualist Demonstration.” My analysis demonstrates that Section 2 is actually a no-fault statute. Section 2 requires courts to impose sanctions on monopolies and attempts to monopolize without inquiring into whether the defendant engaged in anticompetitive conduct or whether it was efficient.

A Brief Primer on Textualism

As most readers know, a traditionalist approach to statutory interpretation analyzes a law’s legislative history and interprets it accordingly. The floor debates in Congress and relevant Committee reports affect how courts interpret a law, especially in close cases or cases where the text is ambiguous. By contrast, textualism only interprets the words and phrases actually used in the relevant statute. Each word and phrase is given its fair, plain, ordinary, and original meaning at the time the statute was enacted.

Justice Scalia and Bryan Garner, a professor at SMU’s Dedman School of Law, wrote a 560-page book explaining and analyzing textualism. Nevertheless, a basic textualist analysis can be described relatively simply. To ascertain the meaning of the relevant words and phrases in the statute, textualism relies mostly upon definitions contained in reliable and authoritative dictionaries of the period in which the statute was enacted. These definitions are supplemented by analyzing the terms as they were used in contemporaneous legal treatises andcases. Crucially, textualism ignores statutes’ legislative history. In the words of Justice Scalia, “To say that I used legislative history is simply, to put it bluntly, a lie.”

Textualism does not attempt to discern what Congress “intended to do” other than by plainly examining the words and phrases in statutes. A textualist analysis does not add or subtract from the statute’s exact language and does not create exceptions or interpret statutes differently in special circumstances. Nor should a textualist judge insert his or her own policy preferences into the interpretation. No requirement should be read into a law unless, of course, it is explicitly contained in the legislation. No exemption should be inferred to achieve some overall policy goal Congress arguably had unless, of course, the text demands it.

As Justice Scalia wrote, “Once the meaning is plain, it is not the province of a court to scan its wisdom or its policy.” Indeed, if a court were to do so this would be the antithesis of textualism. There are some complications relevant to a textualist analysis of Section 2, but they do not change the results that follow.

A Textualist Analysis of Section 2 of the Sherman Act

A straightforward textualist interpretation of Section 2 demonstrates that a violation does not require anticompetitive conduct and applies regardless whether the firm achieved its position through efficient behavior.

Section 2 of the Sherman Act makes it unlawful for any person to “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or commerce among the several States . . . .” There is nothing, no language in Section 2, requiring anticompetitive conduct or creating an exception for efficient monopolies. A textualist interpretation of Section 2 therefore needs only to determine what the terms “monopolize” and “attempt to monopolize” meant in 1890. This examination demonstrates that these terms meant the same things they mean today if they are “fairly,” “ordinarily,” or “plainly” interpreted, free from the legal baggage that has grown up around them by a multitude of court decisions.

What Did “Monopolize” Mean in 1890?

When the Sherman Act was passed the word “monopolize” simply meant to acquire a monopoly. The term was not limited to monopolies acquired or preserved by anticompetitive conduct, and it did not exclude firms that achieved their monopoly due to efficient behavior.

As noted earlier, Justice Scalia was especially interested in the definitions of key terms in contemporary dictionaries. Scalia and Garner believe that six dictionaries published between 1851 to 1900 are “useful and authoritative.” All six were checked for definitions of “monopolize”. The principle definition in each for “monopolize” was simply that a firm had acquired a monopoly. None required anticompetitive conduct for a firm to “monopolize” a market, or excluded efficient monopolies.

For example, the 1897 edition of Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia defined “monopolize” as: “1. To obtain a monopoly of; have an exclusive right of trading in: as, to monopolize all the corn in a district . . . . ”

Serendipitously, a definition of “monopolize” was given in the Sherman Act’s legislative debates, just before the final vote on the Bill. Although normally a textualist does not care about anything uttered during a congressional debate, Senator Edmund’s remarks should be significant to a textualist because he quotes from a contemporary dictionary that Scalia considered useful and reliable. “[T]he best answer I can make to both my friends is to read from Webster’s Dictionary the definition of the verb “to monopolize”: He went on:

1. To purchase or obtain possession of the whole of, as a commodity or goods in market, with the view to appropriate or control the exclusive sale of; as, to monopolize sugar or tea.

There was no requirement of anticompetitive conduct, or exception for a monopoly efficiently gained.

These definitions are essentially the same as those in the 1898 and 1913 editions of Webster’s Dictionary. The four other dictionaries of the period Scalia & Garner considered reliable also contained essentially identical definitions. The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, from 1908, also contained a similar definition of “monopolize:”

1 . . . . To get into one’s hands the whole stock of (a particular commodity); to gain or hold exclusive possession of (a trade); . . . . To have a monopoly. . . . 2 . . . . To obtain exclusive possession or control of; to get or keep entirely to oneself.

Not only does the 1908 Oxford English Dictionary equate “monopolize” with “monopoly,” but nowhere does it require a monopolist to engage in anticompetitive conduct.

Moreover, all but one of the definitions in Scalia’s preferred dictionaries do not limit monopolies to firms making every sale in a market. They roughly correspond to the modern definition of “monopoly power,” by defining “monopolize” as the ability to control a market. The 1908 Oxford English Dictionary defined “monopolize” in part as “To obtain exclusive possession or control of.” The Webster’s Dictionary defined monopolize as “with the view to appropriate or control the exclusive sale of.” Stormonth defined monopolize as “one who has command of the market.” Latham defined monopolize as “ to have the sole power or privilege of vending.…” And Hunter & Morris defined monopolize as “to have exclusive command over.”

In summary, every one of Scalia’s preferred period dictionaries defined “monopolize” as simply to gain all the sales of a market or the control of a market. A textualist analysis of contemporary legal treatises and cases yields the same result. None required conduct we would today characterize as anticompetitive, or exclude a firm gaining a monopoly by efficient means.

A Textualist Analysis of “Attempt to Monopolize”

A textualist interpretation of Section 2 should analyze the word “attempt” as it was used in the phrase “attempt to monopolize” circa 1890. However, no unexpected or counterintuitive result comes from this examination. Circa 1890 “attempt” had its colloquial 21st Century meaning, and there was no requirement in the statute that an “attempt to monopolize” required anticompetitive conduct or excluded efficient attempts.

The “useful and authoritative” 1897 Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia defines “attempt” as:

1. To make an effort to effect or do; endeavor to perform; undertake; essay: as, to attempt a bold flight . . . . 2. To venture upon: as, to attempt the sea.— 3. To make trial of; prove; test . . . . .

The 1898 Webster’s Dictionary gives a similar definition: “Attempt . . . 1. To make trial or experiment of; to try. 2. To try to move, subdue, or overcome, as by entreaty.’ The Oxford English Dictionary, which defined “attempt” in a volume published in 1888, similarly reads: “1. A putting forth of effort to accomplish what is uncertain or difficult….”

However, the word “attempt” in a statute did have a specific meaning under the common law circa 1890. It meant “an intent to do a particular criminal thing, with an act toward it falling short of the thing intended.” One definition stated that the act needed to be “sufficient both in magnitude and in proximity to the fact intended, to be taken cognizance of by the law that does not concern itself with things trivial and small.” But no source of the period defined the magnitude or nature of the necessary acts with great specificity (indeed, a precise definition might well be impossible).

It is noteworthy that in 1881 Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote about the attempt doctrine in his celebrated treatise, The Common Law:

Eminent judges have been puzzled where to draw the line . . . the considerations being, in this case, the nearness of the danger, the greatness of the harm, and the degree of apprehension felt. When a man buys matches to fire a haystack . . . there is still a considerable chance that he will change his mind before he comes to the point. But when he has struck the match . . . there is very little chance that he will not persist to the end . . .

Congress’s choice of the phrase “attempt to monopolize” surely built upon the existing common law definitions of an “attempt” to commit robbery and other crimes. Although the meaning of a criminal “attempt” to violate a law has evolved since 1890, a textualist approach towards an “attempt to monopolize” should be a “fair” or “ordinary” interpretation of these words as they were used in 1890, ignoring the case law that has arisen since then. It is clear that acts constituting mere preparation or planning should be insufficient. Attempted monopolization should also require the intent to take over a market and at least one serious act in furtherance of this plan.

But “attempted monopolization” under Section 2 should not require the type of conduct we today consider anticompetitive, or exempt efficient conduct. Because current case law only imposes sanctions under Section 2 if a court decides the firm engaged in anticompetitive conduct,this case law was wrongly decided. It should be overturned, as should the case law that excuses efficient attempts.

Moreover, attempted monopolization’s current “dangerous probability” requirement should be modified significantly. Today it is quite unusual for a court to find that a firm illegally “attempted to monopolize” if it possessed less than 50 percent of a market.But under a textualist interpretation of Section 2, suppose a firm with only a 30 percent market share seriously tried to take over a relevant market. Isn’t a firm with a 30 percent market share often capable of seriously attempting to monopolize a market? And, of course, attempted monopolization shouldn’t have an anticompetitive conduct requirement or an efficiency exception.

Textualists Should Be Consistent, Even If That Means More Antitrust Enforcement

Where did the exception for efficient monopolies come from? How did the requirement that anticompetitive conduct is necessary for a Section 2 violation arise? They aren’t even hinted at in the text of the Sherman Act. Shouldn’t we recognize that conservative judges simply made up the anticompetitive conduct requirement and efficiency exception because they thought this was good policy? This is not textualism. It’s the opposite of textualism.

No fault monopolization embodies a love for competition and a distaste for monopoly so strong that it does not even undertake a “rule of reason” style economic analysis of the pros and cons of particular situations. It’s like a per se statute insofar as it should impose sanctions on all monopolies and attempts to monopolize. At the remedy stage, of course, conduct-oriented remedies often have been, and should continue to be, found appropriate in Section 2 cases.

The current Supreme Court is largely textualist, but also extremely conservative. Would it decide a no-fault case in the way that textualism mandates?

Ironically, when assessing the competitive effects of the Baker Hughes merger, (then) Judge Thomas changed the language of the statute from “may be substantially to lessen competition” to “will substantially lessen competition,” despite considering himself to be a textualist. So much for sticking to the language of the statute!

Until recently, textualism has only been used to analyze an antitrust law a modest number of times. This is ironic because, even though textualism has historically only been championed by conservatives, a textualist interpretation of the antitrust laws should mean that the antitrust statutes will be interpreted according to these laws’ original aggressive, populist and consumer-oriented language.

Robert Lande is the Venable Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Baltimore Law School.

Over 100 years ago, Congress responded to railroad and oil monopolies’ stranglehold on the economy by passing the United States’ first-ever antitrust laws. When those reforms weren’t enough, Congress created the Federal Trade Commission to protect consumers and small businesses from predation. Today, unchecked monopolies again threaten economic competition and our democratic institutions, so it’s no surprise that the FTC is bringing a historic antitrust suit against one of the biggest fish in the stream of commerce: Amazon.

Make no mistake: modern-day monopolies, particularly the Big Tech giants (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, and Meta), are active threats to competition and consumers’ welfare. In 2020, the House Antitrust Subcommittee concluded an extensive investigation into Big Tech’s monopolistic harms by condemning Amazon’s monopoly power, which it used to mistreat sellers, bully retail partners, and ruin rivals’ businesses through the use of sellers’ data. The Subcommittee’s report found that, as both the operator of and participant in its marketplace, Amazon functions with “an inherent conflict of interest.”

The FTC’s lawsuit builds off those findings by targeting Amazon’s notorious practice of “self-preferencing,” in which the company gathers private data on what products users are purchasing, creates its own copies of those products, then lists its versions above any competitors on user searches. Moreover, by bullying sellers looking to discount their products on other online marketplaces, Amazon has forced consumers to fork over more money than what they would have in a truly-competitive environment.

But perhaps the best evidence of Amazon’s illegal monopoly power is how hard the company has worked for years to squash any investigation into its actions. For decades, Amazon has relied on the classic ‘revolving door’ strategy of poaching former FTC officials to become its lobbyists, lawyers, and senior executives. This way, the company can use their institutional knowledge to fight the agency and criticize strong enforcement actions. These “revolvers” defend the business practices which their former FTC colleagues argue push small businesses past their breaking points. They also can help guide Amazon’s prodigious lobbying efforts, which reached a corporate record in 2022 amidst an industry wide spending spree in which “the top tech companies spent nearly $70 million on lobbying in 2022, outstripping other industries including pharmaceuticals and oil and gas.”

Amazon’s in-house legal and policy shops are absolutely stacked full of ex-FTC officials and staffers. In less than two years, Amazon absorbed more than 28 years of FTC expertise with just three corporate counsel hires: ex-FTC officials Amy Posner, Elisa Kantor Perlman and Andi Arias. The company also hired former FTC antitrust economist Joseph Breedlove as its principal economist for litigation and regulatory matters (read: the guy we’re going to call as an expert witness to say you shouldn’t break us up) in 2017.

It goes further than that. Last year, Amazon hired former Senate Judiciary Committee staffer Judd Smith as a lobbyist after he previously helped craft legislation to rein in the company and other Big Tech giants. Amazon also contributed more than $1 million to the “Competitiveness Coalition,” a Big Tech front group led by former Sen. Scott Brown (R-MA). The coalition counts a number of right-wing, anti-regulatory groups among its members, including the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a notorious purveyor of climate denialism, and National Taxpayers Union, an anti-tax group regularly gifted op-ed space in Fox News and the National Review.

This goes to show the lengths to which Amazon will go to avoid oversight from any government authority. True, the FTC has finally filed suit against Amazon, and that is a good thing. But Amazon, throughout their pursuance of ever growing monopoly power, hired their team of revolvers precisely for this moment. These ex-officials bring along institutional knowledge that will inform Amazon’s legal defense. They will likely know the types of legal arguments the FTC will rely on, how the FTC conducted its pretrial investigations, and the personalities of major players in the case.

This knowledge is invaluable to Amazon. It’s like hiring the assistant coach of an opposing team and gaining access to their playbook — you know what’s coming before it happens and you can prepare accordingly. Not only that, but this stream of revolvers makes it incredibly difficult to know the dedication of some regulators towards enforcing the law against corporate behemoths. How is the public expected to trust its federal regulators to protect them from monopoly power when a large swath of its workforce might be waiting for a monopoly to hire them? (Of course, that’s why we need both better pay for public servants as well as stricter restrictions on public servants revolving out to the corporations they were supposedly regulating.)

While spineless revolvers make a killing defending Amazon, the actual people and businesses affected by their strong arming tactics are applauding the FTC’s suit. Following the FTC’s filing, sellers praised the Agency on Amazon’s Seller Central forum, calling it “long overdue” and Amazon’s model as a “race to the bottom.” One commenter even wrote they will be applying to the FTC once Amazon’s practices force them off the platform. This is the type of revolving we may be able to support. When the FTC is staffed with people who care more about reigning in monopolies than receiving hefty paychecks from them in the future (e.g., Chair Lina Khan), we get cases that actually protect consumers and small businesses.

The FTC’s suit against Amazon signals that the federal government will no longer stand by as monopolies hollow-out the economy and corrupt the inner-workings of our democracy, but the revolvers will make every step difficult. They will be in the corporate offices and federal courtrooms advising Amazon on how best to undermine their former employer’s legal standing. They will be in the media, claiming to be objective as a former regulator, while running cover for Amazon’s shady practices that the business press will gobble up. The prevalence of these revolvers makes it difficult for current regulators to succeed while simultaneously undermining public trust in a government that should work for people, not corporations. Former civil servants who put cash from Amazon over the regulatory mission to which they had once been committed are turncoats to the public good. They should be scorned by the public and ignored by government officials and media alike.

Andrea Beaty is Research Director at the Revolving Door Project, focusing on anti-monopoly, executive branch ethics and housing policy. KJ Boyle is a research intern with the Revolving Door Project. Max Moran is a Fellow at the Revolving Door Project. The Revolving Door Project scrutinizes executive branch appointees to ensure they use their office to serve the broad public interest, rather than to entrench corporate power or seek personal advancement.

The Federal Trade Commission has accused Amazon of illegally maintaining its monopoly, extracting supra-competitive fees on merchants that use Amazon’s platform. If and when the fact-finder determines that Amazon violated the antitrust laws, we propose structural remedies to address the competitive harms. Behavioral remedies have fallen out of favor among antitrust scholars. But the success of a structural remedy cannot be taken for granted.

To briefly review the bidding, the FTC’s Complaint alleges that Amazon prevents merchants from steering customers to a lower-cost platform—that is, a platform that charges a lower take rate—by offering discounts off the price it charges on Amazon. Amazon threatens merchants’ access to the Buy Box if merchants are caught charging a lower price outside of Amazon, a variant of a most-favored-nation (MFN) restriction. In other words, Amazon won’t allow merchants to share any portions of its savings with customers as an inducement to switch platforms; doing so would put downward pressure on Amazon’s take rate, which has climbed from 35 to 45 percent since 2020 per ILSR.

The Complaint also alleges that Amazon ties its fulfillment services to access to Amazon Prime. Given the importance of Amazon Prime to survival on Amazon’s Superstore, Amazon’s policy is effectively conditioning a merchant’s access to its Superstore on an agreement to purchase Amazon’s fulfillment, often at inflated rates. Finally, the Complaint alleges that Amazon gives its own private-label brands preference in search results.

These are classic exclusionary restraints that, in another era, would be instinctively addressed via behavioral remedies. Ban the MFN, ban the tie-in, and ban the self-preferencing. But that would be wrongheaded, as doing so would entail significant oversight by enforcement authorities. As the DOJ Merger Remedies Manual states, “conduct remedies typically are difficult to craft and enforce.” To the extent that a remedy is fully conduct-based, it should be disfavored. The Remedies Manual appears to approve of conduct relief to facilitate structural relief, “Tailored conduct relief may be useful in certain circumstances to facilitate effective structural relief.”

Instead, there should be complete separation of the fulfillment services from the Superstore. In a prior piece for The Sling, we discussed two potential remedies for antitrust bottlenecks—the Condo and the Coop. In what follows, we explain that the Condo approach is a potential remedy for the Amazon platform bottleneck and the Coop approach a good remedy for the fulfillment center system. Our proposed remedy has the merit of allowing for market mechanisms to function to bypass the need for continued oversight after structural remedies are deployed.

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

Structural remedies to monopolization have, in the past, created worry about continued judicial oversight and regulation. “No one wants to be Judge Greene.” He spent the bulk of his remaining years on the bench having his docket monopolized by disputes arising from the breakup of AT&T. Breakup had also been sought in the case of Microsoft. But the D.C. Circuit, citing improper communications with the press prior to issuance of Judge Jackson’s opinion and his failure to hold a remedy hearing prior to ordering divestiture of Microsoft’s operating system from the rest of the company, remanded the case for determination of remedy to Judge Kollar-Kotelly.

By that juncture of the proceeding, a new Presidential administration brought a sea change by opposing structural remedies not only in this case but generally. Such an anti-structural policy conflicts with the pro-structural policy set forth in Standard Oil and American Tobacco—that the remedy for unlawful monopolization should be restructuring the enterprises to eliminate the monopoly itself. The manifest problem with the AT&T structural remedy and the potential problem with the proposed remedy in Microsoft is that neither removed the core monopoly power that existed, thus retaining incentives to engage in anticompetitive conduct and generating continued disputes.

The virtue of the structural approaches we propose is that once established, they should require minimal judicial oversight. The ownership structures would create incentives to develop and operate the bottlenecks in ways that do not create preferences or other anticompetitive conduct. With an additional bar to re-acquisition of critical assets, such remedies are sustainable and would maximize the value of the bottlenecks to all stakeholders.

Turn Amazon’s Superstore into a Condo

The condominium model is one in which the users would “own” their specific units as well as collectively “owning” the entire facility. But a distinct entity would provide the administration of the core facility. Examples of such structures include the current rights to capacity on natural gas pipelines, rights to space on container ships, and administration for standard essential patents and for pooled copyrights. These examples all involve situations in which participants have a right to use some capacity or right but the administration of the system rests with a distinct party whose incentive is to maximize the value of the facility to all users. In a full condominium analogy, the owners of the units would have the right to terminate the manager and replace it. Thus, as long as there are several potential managers, the market would set the price for the managerial service.

A condominium mode requires the easy separability of management of the bottleneck from the uses being made of it. The manager would coordinate the uses and maintain the overall facility while the owners of access rights can use the facility as needed.

Another feature of this model is that when the rights of use/access are constrained, they can be tradable; much as a condo owner may elect to rent the condo to someone who values it more. Scarcity in a bottleneck creates the potential for discriminatory exploitation whenever a single monopolist holds those rights. Distributing access rights to many owners removes the incentive for discriminatory or exclusionary conduct, and the owner has only the opportunity to earn rents (high prices) from the sale or lease of its capacity entitlement. Thus, dispersion of interests results in a clear change in the incentives of a rights holder. This in turn means that the kinds of disputes seen in AT&T’s breakup are largely or entirely eliminated.

The FTC suggests skullduggery in the operation of the Amazon Superstore. Namely, degrading suggestions via self-preferencing:

Amazon further degrades the quality of its search results by buying organic content under recommendation widgets, such as the “expert recommendation” widget, which display Amazon’s private label products over other products sold on Amazon.

Moreover, in a highly redacted area of the complaint, the FTC alleges that Amazon has the ability to “profitably worsen its services.”

The FTC also alleges that Amazon bars customers from “multihoming:”

[Multihoming is] simultaneously offering their goods across multiple online sales channels. Multihoming can be an especially critical mechanism of competition in online markets, enabling rivals to overcome the barriers to entry and expansion that scale economies and network effects can create. Multihoming is one way that sellers can reduce their dependence on a single sales channel.

If the Superstore were a condo, the vendors would be free to decide how much to focus on this platform in comparison to other platforms. Merchants would also be freed from the MFN, as the condo owner would not attempt to ban merchants from steering customers to a lower-cost platform.

Condominiumization of the Amazon Superstore would go a long way to reducing what Cory Doctorow might call the “enshittification” of the Amazon Superstore. Given its dominance over merchants, it would probably be necessary to divest and rebrand the “Amazon basics” business. Each participating vendor (retailer or direct selling manufacturer) would share in the ownership of the platform and would have its own place to promote its line of goods or services.