The Justice Department’s pending antitrust case against Google, in which the search giant is accused of illegally monopolizing the market for online search and related advertising, revealed the nature and extent of a revenue sharing agreement (“RSA”) between Google and Apple. Pursuant to the RSA, Apple gets 36 percent of advertising revenue from Google searches by Apple users—a figure that reached $20 billion in 2022. The RSA has not been investigated in the EU. This essay briefly recaps the EU law on remedies and explains why choice screens, the EU’s preferred approach, are the wrong remedy focused on the wrong problem. Restoring effective competition in search and related advertising requires (1) the dissolution of the RSA, (2) the fostering of suppressed publishers and independent advertisers, and (3) the use of an access remedy for competing search-engine-results providers.

EU Law on Remedies

EU law requires remedies to “bring infringements and their effects to an end.” In Commercial Solvents, the Commission power was held to “include an order to do certain acts or provide certain advantages which have been wrongfully withheld.”

The Commission team that dealt with the Microsoft case noted that a risk with righting a prohibition of the infringement was that “[i]n many cases, especially in network industries, the infringer could continue to reap the benefits of a past violation to the detriment of consumers. This is what remedies are intended to avoid.” An effective remedy puts the competitive position back as it was before the harm occurred, which requires three elements. First, the abusive conduct must be prohibited. Second, the harmful consequences must be eliminated. For example, in Lithuanian Railways, the railway tracks that had been taken away were required to be restored, restoring the pre-conduct competitive position. Third, the remedy must prevent repetition of the same conduct or conduct having an “equivalent effect.” The two main remedies are divestiture and prohibition orders.

The RSA Is Both a Horizontal and a Vertical Arrangement

In the 2017 Google Search (Shopping) case, Google was found to have abused its dominant position in search. In the DOJ’s pending search case, Google is also accused of monopolizing the market for search. In addition to revealing the contours of the RSA, the case revealed a broader coordination between Google and Apple. For example, discovery revealed there are monthly CEO-to-CEO meetings where the “vision is that we work as if we are one company.” Thus, the RSA serves as much more than a “default” setting—it is effectively an agreement not to compete.

Under the RSA, Apple gets a substantial cut of the revenue from searches by Apple users. Apple is paid to promote Google Search, with the payment funded by income generated from the sale of ads to Apple’s wealthy user base. That user base has higher disposable income than Android users, which makes it highly attractive to those advertising and selling products. Ads to Apple users are thought to generate 50 percent of ad spend but account for only 20 percent of all mobile users.

Compared to Apple’s other revenue sources, the scale of the payments made to Apple under the RSA is significant. It generates $20 billion in almost pure profit for Apple, which accounts for 15 to 20 percent of Apple’s net income. A payment this large and under this circumstance creates several incentives for Apple to cement Google’s dominance in search:

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google Search. This encompasses a form of product placement through which Apple is paid to promote and display Google’s search bar prominently on its products as the default. As promotion and display is itself a form of abuse, the treatment provides a discriminatory advantage to Google.

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google’s sales of search ads. To increase its own income, Apple has an incentive to ensure that Google Search ads are more successful than rival online ads in attracting advertisers. Because advertisers’ main concern is their return on their advertising spend, Google’s Search ads need to generate a higher return on advertising investment than rival online publishers.

- Apple is incentivized to introduce ad blockers. This is one of a series of interlocking steps in a staircase of abuses that block any player (other than Google) from using data derived from Apple users. Blocking the use of Apple user data by others increases the value of Google’s Search ads and Apple’s income from Apple’s high-end customers.

- Apple is incentivized to block third-party cookies and the advertising ID. This change was made in its Intelligent Tracking Prevention browser update in 2017 and in its App Tracking Transparency pop-up prompt update in 2020. Each step further limits the data available to competitors and drives ad revenue to Google search ads.

- Apple has a disincentive to build a competing search engine or allow other browsers on its devices to link to competing search engines or the Open Web. This is because the Open Web acts as a channel for advertising in competition with Google.

- Apple has a disincentive to invest in its browser engine (WebKit). This would allow users of the Open Web to see the latest videos and interesting formats for ads on websites. Apple sets the baseline for the web and underinvests in Safari to that end, preventing rival browsers such as Mozilla from installing its full Firefox Browser on Apple devices.

The RSA also gives Google an incentive to support Apple’s dominance in top end or “performance smartphones,” and to limit Android smartphone features, functions and prices in competition with Apple. In its Android Decision, the EU Commission found significant price differences between Google Android and iOS devices, while Google Search is the single largest source of traffic from iPhone users for over a decade.

Indeed, the Department of Justice pleadings in USA v. Apple show how Apple has sought to monopolize the market for performance smartphones via legal restrictions on app stores and by limiting technical interoperability between Apple’s system and others. The complaint lists Apple’s restrictions on messaging apps, smartwatches, and payments systems. However, it overlooks the restrictions on app stores from using Apple users’ data and how it sets the baseline for interoperating with the Open Web.

It is often thought that Apple is a devices business. On the contrary, the size of its RSA with Google means Apple’s business, in part, depends on income from advertising by Google using Apple’s user data. In reality, Apple is a data-harvesting business, and it has delegated the execution to Google’s ads system. Meanwhile, its own ads business is projected to rise to $13.7 billion by 2027. As such, the RSA deserves very close scrutiny in USA v. Apple, as it is an agreement between two companies operating in the same industry.

The Failures of Choice Screens

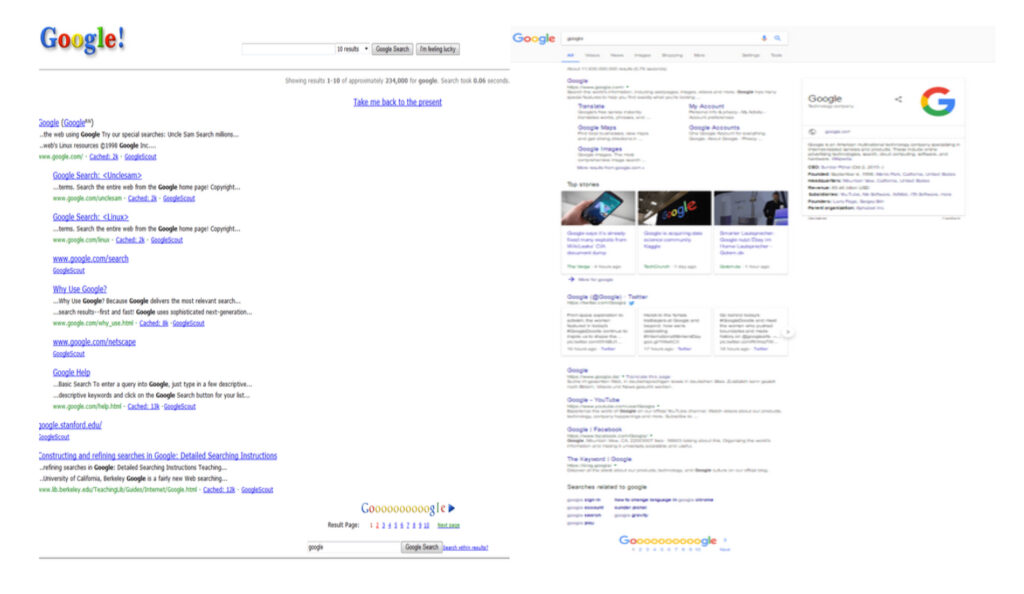

The EU Google (Search) abuse consisted in Google’s “positioning and display” of its own products over those of rivals on the results pages. Google’s underlying system is one that is optimized for promoting results by relevance to user query using a system based on Page Rank. It follows that promoting owned products over more relevant rivals requires work and effort. The Google Search Decision describes this abuse as being carried out by applying a relevance algorithm to determine ranking on the search engine results pages (“SERPs”). However, the algorithm did not apply to Google’s own products. As the figure below shows, Google’s SERP has over time filled up with own products and ads.

To remedy the abuse, the Decision compelled Google to adopt a “Choice Screen.” Yet this isn’t an obvious remedy to the impact on competitors that have been suppressed, out of sight and mind, for many years. The choice screen has a history in EU Commission decisions.

In 2009, the EU Commission identified the abuse Microsoft’s tying of its web browser to its Windows software. Other browsers were not shown to end users as alternatives. The basic lack of visibility of alternatives was the problem facing the end user and a choice screen was superficially attractive as a remedy, but it was not tested for efficacy. As Megan Grey observed in Tech Policy Press, “First, the Microsoft choice screen probably was irrelevant, given that no one noticed it was defunct for 14 months due to a software bug (Feb. 2011 through July 2012).” The Microsoft case is thus a very questionable precedent.

In its Google Android case, the European Commission found Google acted anticompetitively by tying Google Search and Google Chrome to other services and devices and required a choice screen presenting different options for browsers. It too has been shown to be ineffective. A CMA Report (2020) also identified failures in design choices and recognized that display and brand recognition are key factors to test for choice screen effectiveness.

Giving consumers a choice ought to be one of the most effective ways to remedy a reduction of choice. But a choice screen doesn’t provide choice of presentation and display of products in SERPs. Presentations are dependent on user interactions with pages. And Google’s knowledge of your search history, as well as your interactions with its products and pages, means it presents its pages in an attractive format. Google eventually changed the Choice Screen to reflect users top five choices by Member State. However, none of these factors related to the suppression of brands or competition, nor did it rectify the presentation and display’s effects on loss of variety and diversity in supply. Meanwhile, Google’s brand was enhanced from billions of user’s interactions with its products.

Moreover, choice screens have not prevented rival publishers, providers and content creators from being excluded from users’ view by a combination of Apple’s and Google’s actions. This has gone on for decades. Alternative channels for advertising by rival publishers are being squeezed out.

A Better Way Forward

As explained above, Apple helps Google target Apple users with ads and products in return for 36 percent of the ad revenue generated. Prohibiting that RSA would remove the parties’ incentives to reinforce each other’s market positions. Absent its share of Google search ads revenue, Apple may find reasons to build its own search engine or enhance its browser by investing in it in a way that would enable people to shop using the Open Web’s ad funded rivals. Apple may even advertise in competition with Google.

Next, courts should impose (and monitor) a mandatory access regime. Applied here, Google could be required to operate within its monopoly lane and run its relevance engine under public interest duties in “quarantine” on non-discriminatory terms. This proposal has been advanced by former White House advisor Tim Wu:

I guess the phrase I might use is quarantine, is you want to quarantine businesses, I guess, from others. And it’s less of a traditional antitrust kind of remedy, although it, obviously, in the ‘56 consent decree, which was out of an antitrust suit against AT&T, it can be a remedy. And the basic idea of it is, it’s explicitly distributional in its ideas. It wants more players in the ecosystem, in the economy. It’s almost like an ecosystem promoting a device, which is you say, okay, you know, you are the unquestioned master of this particular area of commerce. Maybe we’re talking about Amazon and it’s online shopping and other forms of e-commerce, or Google and search.

If the remedy to search abuse were to provide access to the underlying relevance engine, rivals could present and display products in any order they liked. New SERP businesses could then show relevant results at the top of pages and help consumers find useful information.

Businesses, such as Apple, could get access to Google’s relevance engine and simply provide the most relevant results, unpolluted by Google products. They could alternatively promote their own products and advertise other people’s products differently. End-users would be able to make informed choices based on different SERPs.

In many cases, the restoration of competition in advertising requires increased familiarity with the suppressed brand. Where competing publishers’ brands have been excluded, they must be promoted. Their lack of visibility can be rectified by boosting those harmed into rankings for equivalent periods of time to the duration of their suppression. This is like the remedies used for other forms of publication tort. In successful defamation claims, the offending publisher must publish the full judgment with the same presentation as the offending article and displayed as prominently as the offending article. But the harm here is not to individuals; instead, the harm redounds to alternative publishers and online advertising systems carrying competing ads.

In sum, the proper remedy is one that rectifies the brand damage from suppression and lack of visibility. Remedies need to address this issue and enable publishers to compete with Google as advertising outlets. Identifying a remedy that rectifies the suppression of relevance leads to the conclusion that competition between search-results-page businesses is needed. Competition can only be remedied if access is provided to the Google relevance engine. This is the only way to allow sufficient competitive pressure to reduce ad prices and provide consumer benefits going forward.

The authors are Chair Antitrust practice, Associate, and Paralegal, respectively, of Preiskel & Co LLP. They represent the Movement for an Open Web versus Google and Apple in EU/US and UK cases currently being brought by their respective authorities. They also represent Connexity in its claim against Google for damages and abuse of dominance in Search (Shopping).

For those not steeped in antitrust law’s treatment of single-firm monopolization cases, under the rule-of-reason framework, a plaintiff must first demonstrate that the challenged conduct by the defendant is anticompetitive; if successful, the burden shifts to the defendant in the second or balancing stage to justify the restraints on efficiency grounds. According to research by Professor Michael Carrier, between 1999 and 2009, courts dismissed 97 percent of cases at the first stage, reaching the balancing stage in only two percent of cases.

There is a fierce debate in antitrust circles as to what constitutes a cognizable efficiency. In April, the Ninth Circuit upheld Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers’ dismissal of Epic Game’s antitrust case against Apple on the flimsiest of efficiencies.

A brief recap of the case is in order, beginning with the challenged conduct. Epic alleged Apple forces certain app developers to pay monopoly rents and exclusively use its App Store, and in addition requires the use of Apple’s payment system for any in-app purchases. The use of Apple’s App Store, and the prohibition on a developer loading its own app store, as well as the required use of Apple’s payment system are set forth in several Apple contracts developers must execute to operate on Apple’s iOS. The Ninth Circuit found that Epic met its burden of demonstrating an unreasonable restraint of trade, but Epic’s case failed because Apple was able to proffer two procompetitive rationales that the Appellate Court held were non-pretextual and legally cognizable. One of those justifications was that Apple prohibited competitive app stores and required developers to only use Apple’s payment system because it was protecting its intellectual property (“IP”) rights.

Yet neither the District Court nor the Ninth Circuit ever tell us what IP Apple’s restraints are protecting. The District Court opinion states that “Apple’s R&D spending in FY 2020 was $18.8 billion,” and that Apple has created “thousands of developer tools.” But even Apple disputes in a recent submission to the European Commission that R&D has any relationship to the value of IP: “A patent’s value is traditionally measured by the value of the claimed technology, not the amount of effort expended by the patent holder in obtaining the patent, much less ‘failed investments’ that did not result in any valuable patented technology.”

Moreover, every tech platform must invest something to encourage participation by developers and users. Without the developers’ apps, however, there would be few if any device sales. If all that is required to justify exclusion of competitors, as well tying and monopolization, is the existence of some unspecified IP rights, then exclusionary conduct by tech platforms for all practical purposes becomes per se legal. Plaintiffs challenging these tech platform practices on antitrust grounds are doomed from the start. Even though the plaintiff theoretically can proffer a less restrictive alternative for the tech platform owners to monetize their IP, this alternative per the Ninth Circuit must be “virtually as effective” and “without increased cost.” Again, the deck was already stacked against plaintiffs, and this decision risks making it even less likely for abusive monopolists to be held to account.

Ignoring the Economic Literature on IP

In addition to bestowing virtual antitrust immunity on tech platforms in rule-of-reason cases, there are important reasons why IP should never qualify as a procompetitive business justification for exclusionary conduct. Had the Ninth Circuit consulted the relevant economic literature, it would have learned that IP is fundamentally not procompetitive. Indeed, there is virtually no evidence that patents and copyrights, particularly in software, incentivize or create innovation. As Professors Michele Boldrin and David Levine conclude, “there is no empirical evidence that [patents] serve to increase innovation and productivity…” This same claim could be made for the impact of copyrights as well. Academic studies find little connection between patents, copyright, and innovation. Historical analysis similarly disputes the connection. Surveys of companies further find that the goals of patenting are not primarily to stimulate innovation but instead the “prevention of rivals from patenting related inventions.” Or, in other words, the creation of barriers to entry. Innovation within individual firms is motivated much more by gaining first-mover advantages, moving quickly down the learning curve or developing superior sales and marketing in competitive markets. As Boldrin and Levine explain:

In most industries, the first-mover advantage and the competitive rents it induces are substantial without patents. The smartphone industry-laden as it is with patent litigation-is a case in point. Apple derived enormous profits in this market before it faced any substantial competition.

Possibly even more decisive for innovation are higher labor costs that result from strong unions. Other factors have also been found to be important for innovation. The government is responsible for 57 percent of all basic research, research that has been the foundation of the internet, modern agriculture, drug develop, biotech, communications and other areas. Strong research universities are the source of many more significant innovations than private firms. Professor Margaret O’Mara’s recent history of Silicon Valley demonstrates how military contracts and relationships with Stanford University were absolutely critical to the Silicon Valley success story. Her book reveals the irony of how the Silicon Valley leaders embraced libertarian ideologies while at the same time their companies were propelled forward by government contracts.

In an earlier period, the antitrust agencies ordered thousands of compulsory licensing decrees, which were estimated to have covered between 40,000 and 50,000 patents. Professor F.M. Scherer shows how these licenses did not lead to less innovation. Indeed, the availability of this technology led to significant economic advances in the United States. In his book, “Inventing the electronic Century,” Professor Alfred Chandler documents how Justice Department consent decrees with RCA, AT&T and IBM, which made important patents available to even rivals, created enormous competition and innovation in data processing, consumer electronics, and telecommunications. The evidence is that limiting or abolishing patent protection has far more beneficial impact than its protection, let alone allowing its use to justify anticompetitive exclusion.

Probably the weakest case for the economic value of patents exists in the software industry. Bill Gates, reflecting on patents in the software industry said in 1991 that:

If people had understood how patents would be granted when most of today’s ideas were invented and had taken out patents, the industry would be at a complete standstill today…A future start-up with no patents of its own will be forced to pay whatever price the giants choose to impose.

The point is that there is very little support for antitrust courts to elevate IP to a justification for market exclusion. The case for procompetitive benefits from patents is nonexistent, while much evidence supports an exclusionary motive for obtaining IP by big tech firms.

As Professors James Bessen and Michael Meurer show, patents on software are particularly problematic because they have high rates of litigation, are of little value, and many appear to be trivial. In particular, Bessen and Meurer argue that many software patents are obvious and therefore invalid. Moreover, the claim boundaries are “fuzzy” and therefore infringement is expensive to resolve.

When asserted in a rule-of-reason case under the Apple precedent, software patents would seem to escape all scrutiny. The defendant would simply assert IP protection without any obligation to reveal with specificity the nature of the IP. The plaintiff then would have no way to challenge validity or infringement or to be able to demonstrate an ability to design around the defendant’s IP. Instead, they must show, per the Ninth Circuit’s opinion, that there is a less restrictive way for the plaintiff to be paid for its IP that is “virtually as effective” and “without increased cost.” This makes no sense at all. It would make far more sense to force any tech platform that seeks to exclude competitors on the basis of IP to simply file a counterclaim to the antitrust complaint alleging patent or copyright infringement and seeking an injunction that excludes the plaintiff. In such a case, the platform’s IP can be tested for validity. The exclusion by the antitrust defendant can be compared to the patent grant, and patent misuse can be examined.

Ignoring Its Own Precedent

It is unfortunate that the Apple court did not take seriously the Circuit’s earlier analysis in Image Technical Services v. Eastman Kodak. There, Kodak defended its decision to tie its parts and service in the aftermarket by claiming that some of its parts were patented. The Court noted that “case law supports the proposition that a holder of a patent or copyright violates the antitrust laws by ‘concerted and contractual behavior that threatens competition.’” The Kodak Court’s example of such prohibited conduct was tying, a claim made by Epic. Because we know that there are numerous competing payment systems, and because nothing in the Ninth Circuit’s opinion addresses the specifics of Apple’s IP that must be protected, it is likely the case that Apple does not have blocking patents that preclude use of alternative payment systems. And if this is the case, Epic alleged the very situation where the Ninth Circuit earlier (citing Supreme Court precedent) found that patents or copyrights violate the antitrust laws. Moreover, the Ninth Circuit thought it was significant that Kodak refused to allow use of both patented or copyrighted products and non-protected products. This may also be true of Apple’s development license in the Epic case. The Court didn’t seem to think that an inquiry into what IP was licensed by these agreements to be significant.

In sum, use of IP as a procompetitive business justification has no place in rule-of-reason cases. There is no evidence IP is procompetitive, and use of IP as a business justification relieves the antitrust defendant of the burden to demonstrate validity and infringement required in IP cases. It further stacks the deck in rule-of-reason cases against plaintiffs, and unjustly favors exclusionary practices by dominant tech platforms.

Mark Glick is a professor in the economics department of the University of Utah.