It’s always better to be a monopolist. “Ruinous competition” is a drag on a company’s profits, particularly when slothful incumbents are forced to compete on the merits. In the case of banks, competition on the merits means increasing rates on deposits for customers with sizeable savings or decreasing overdraft fees for customers with limited funds.

Last week, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finalized a rule that requires financial institutions, credit card issuers, and other financial providers to unlock a customer’s personal financial data—including her transaction history—and transfer it to another provider at the consumer’s request for free. It marks the CFPB’s attempt to activate dormant legal authority of Section 1033 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act. Officially dubbed the “Personal Financial Data Rights” rule, or more casually the “Open Banking” rule, the measure was greeted by those in the budding anti-monopolist movement with glee.

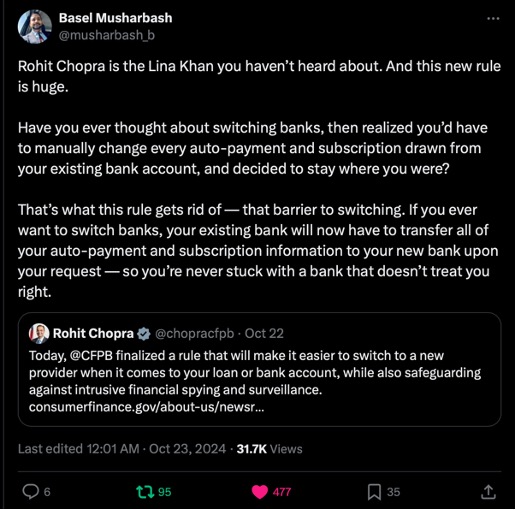

Indeed, FTC Chair Lina Khan, the ultimate champion of competition, tweeted an endorsement of the CFPB’s new rule.

But it wasn’t all rave reviews. The Open Banking rule was also greeted by a swift lawsuit from the Bank Policy Institute (BPI), alleging that the bureau exceeded its statutory authority. The lawsuit also claims the rule risks the “safety and soundness” of the banking system by limiting banks’ discretion to deny upstart banks access to transaction histories. Based on its website, BPI’s membership includes JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Barclays, or what I will call the “incumbent banks.” And JP Morgan’s Jaime Dimon is the Chairman of BPI. Why are the incumbent banks so angry about being compelled to share these transaction histories with upstarts, when such data are arguably the property of the banks’ clients in the first place?

When I first heard about the CFPB’s new rule, I didn’t understand why I needed a regulatory intervention to play one bank off another. For example, after being offered a high CD rate by a scrappy bank, I asked my stodgy bank to match it, only to be ignored by my stodgy bank; I proceeded to write a check from the stodgy bank to the scrappier rival. But having studied the issue, I now understand the particular market failure that the rule seeks to address.

The Rule Would Induce More Aggressive Offers by Upstart Banks

When an upstart bank seeks to pick off a customer from an incumbent bank, the upstart would prefer to extend the most aggressive offer possible, as an inducement to overcome any switching costs that customer might incur. (Fun fact: When interest rates were regulated and interest on checking accounts was banned, banks used to compete by offering toasters to customers at rival banks!) Today’s competitive offer by a rival bank might include a host of ancillary services or “cross-sales” alongside a checking account, such as a credit card, a loan, a line of credit, and payment services. The terms of such offers are governed by the customer’s creditworthiness.

And that’s the catch—the incumbent bank and only the incumbent bank has access to the customer’s transaction history, which includes nuggets like your history of maintaining a balance, overdraft tendencies, and relative timing of payments to income streams. The scrappy upstart, by contrast, is flying blind. And this granular information cannot be obtained through the purchase of a credit report.

Economists refer to such a predicament as “asymmetric information,” and in 2001 three economists even won a Nobel prize for explaining how such asymmetries lead to market failures. In the absence of this information, when formulating its offer, the upstart bank must assume the average tendencies of the borrower based on some peer group, or even worse, it might hedge by assuming the borrower’s creditworthiness is slightly worse than average. As a result, the competitive offer is unnecessary weaker than it could be, and too many customers are sticking with their stodgy (and stingy) bank.

(A fun digression: Some employers inject provisions into a worker’s employment contract that create similar frictions to substitution, which relaxes competitive pressure on wages. You’ve likely heard of a non-compete, which is the ultimate friction. But you may not have heard of a “right-to-match” provision, which gives the incumbent employer a right to match any outside offer from a rival employer. Because the rival employer knows of the provision, and because it’s costly for the rival to formulate an offer, most rivals will give up and the employee never enjoys the benefit of competition.)

The purpose of the Open Banking rule is to induce more aggressive offers by upstart banks and thereby overcome the switching costs associated with changing one’s bank. Put differently, it juices the part of the fin-tech community that seeks to assist consumers, which likely explains the narrow opposition to the rule from incumbent players only. Suppose the customer’s switching costs are $100 and the (weakened) offer from an upstart would improve the customer by $90; under those circumstances, the customer stays put. But if the rule can induce more aggressive offers, boosting the customer benefits of switching to (say) $200, the customer moves. Or she now, with a powerful offer in hand, credibly threatens to switch banks and her stodgy bank improves her terms.

The Open Banking Rule Could Generate Billions in Annual Benefits

The economists of the CFPB have tried to value what this enhanced competition might mean for bank customers. At page 525 of the rule, in a section titled “Potential Benefits and Costs to Consumers and Covered Persons,” the economists explain their valuation methodology:

First, those consumers who switch may earn higher interest rates or pay lower fees. To estimate the potential size of this benefit, the CFPB assumes for this analysis that of the approximately $19 trillion 207 in domestic deposits at FDIC- and NCUA-insured institutions, a little under a third ($6 trillion) are interest-bearing deposits held by consumers, as opposed to accounts held by businesses or noninterest-bearing accounts. If, due to the rule, even one percent of consumer deposits were shifted from lower earning deposit accounts to those with interest rates one percentage point (100 basis points) higher, consumers would earn an additional $600 million annually in interest. Similarly, if due to the rule, consumers were able to switch accounts and thereby avoid even one percent of the overdraft and NSF fees they currently pay, they would pay at least $77 million less in fees per year.

Hence, bank customers who switch banks due to more robust competitive offers made possible by the Open Banking rule would benefit by $677 million per year, based on very conservative assumptions about substitution. And this estimate does not include benefits created for those customers who stay put but nevertheless benefit from the mere threat of leaving. The economists explain that competitive reactions by incumbent banks could lead to a doubling of the aforementioned benefits, to the extent that interest rates on deposits of the non-switchers increase by a mere one basis point. Those benefits would be a transfer from incumbent banks to consumers.

Beware of Fraud Arguments

The Open Banking rule requires that a bank make “covered data” available in electronic form to consumers and to certain “authorized third parties” aka the upstart banks. Covered data includes information about transactions, costs, charges, and usage. The rule spells out what an authorized third party must do to get the covered data, as well as what the “data provider” (aka the incumbent bank) must do upon receiving such a request. The data provider will run its normal fraud review process upon receipt of a data request. Indeed, CFPB even included a provision that states when the data provider has a “legitimate risk management concern,” that concern may trump the data sharing rule.

So any claim that the BPI lawsuit is motivated to protect consumers against fraud or to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking system seems farfetched. The more likely motivation for the challenge is that the Open Banking rule will spur competition among banks, and hence put downward pressure on the incumbent banks’ hefty margins. To wit, JP Morgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, has thrived in a rising rate environment, posting record net income figures since 2022. As the CFPB economists estimate, the rule could raise rates on deposits and reduce rates on overdraft fees, cutting into these record margins. In a similar vein, the CFPB’s new rule might spark competition in the nascent payment system market. Some large banks would like to build their own payment systems (think BoA’s Zelle). By compelling the incumbent banks to share their customers’ transaction histories, however, the Open Banking rule reduces the costs for a scrappy entrant to build a competing payment system. If pay-by-bank gets going, it will be a threat to the incumbent banks’ lucrative credit card and debit card interchange fees. And that threat alone provides billions of reasons to sue the CFPB.

Last month, Capital One announced that it plans to purchase Discover in a deal worth $35.3 billion. For their campaign to secure regulatory approval, Capital One is trying to act like a benevolent pro-consumer company that will use economies of scale to lower interest rates and ramp up competition with Visa and Mastercard. But that’s probably baloney.

There’s something missing in the conversation around this merger–namely, along what axis competition among card issuers actually happens. Most coverage seems to assume that everything can be grouped into “costs for consumers,” but that’s not the case. To really get at what the deal’s competitive effects would be, we need to understand what kinds of companies Capital One and Discover are, the industries in which they operate, and what competition in those spaces looks like.

Subprime Borrowers Are Likely to Be Injured

There’s a lot of uncertainty about how regulators will handle this deal. For one, there are a lot of different agencies involved in overseeing credit card competition. In order to go anywhere, the merger first requires sign off by both the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve Board (Fed). This is because Capital One is a nationally chartered bank, making the OCC its primary regulator, while Discover is regulated primarily as a bank holding company, which is the Fed’s ambit. To add more acronyms, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), while not primarily involved in the merger approval, could play an advisory role, especially since it is the primary regulator of Discover Bank, which is owned by Discover. Similarly, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) could flag issues with the merger as it serves as a secondary regulator for all large financial institutions. Finally, the Department of Justice (DOJ) could review the merger under the antitrust laws.

While the OCC, Fed, and FDIC have all dragged their feet in updating merger guidelines and have a history of rubber-stamping bank consolidation, the CFPB and DOJ are significant hurdles. The CFPB’s Rohit Chopra and DOJ’s Jonathan Kanter are both ardent anti-monopolists. Under Chopra, the CFPB has been aggressive in reining in the worst abuses from financial services companies. Kanter, for his part, has also implied a willingness to take on bank mergers that other regulators approved. The DOJ also has a bit more latitude to flex its muscles with financial network mergers than when two traditional banks merge.

The most obvious merger harm, on which the DOJ will focus like a laser, is whether the merger will allow the combined firm to raise interest rates on cardholders. Capital One and Discover both cater to subprime (credit score in the 600s) borrowers. And there is less competition for subprime borrowers, which is part of why Capital One was a successful upstart in the credit card industry to begin with. Given that subprime borrowers already have the most limited options in where they can get credit, and given that these cardholders likely shop for credit cards based on which offers the lowest interest rate, it follows that the merger could cause significant harm to an especially at-risk consumer base. The DOJ should define a market (or submarket) for subprime cardholders.

Even for those cardholders with higher credit scores who may not consider interest rates while selecting a card, card issuers do compete on rewards programs, security measures, annual fees, and other features. The merger could eliminate competition between Capital One and Discover on those dimensions as well.

Be Skeptical of Purported Benefits to Merchants

In addition to the horizontal competition mentioned above, Capital One will also gain Discover’s payment processing network, which constitutes vertical integration. As a result, the merged firm will simultaneously hold more market share in credit card issuing, becoming the single largest firm in the space, while also operating a payment network. The deal would, unequivocally, decrease competition in the card issuer space, where just ten firms dominate the industry. But what will happen on the payment processing side is less clear. Capital One argues this aspect of the deal will enhance competition. But for whom?

Card processing is a space dominated by just two firms: Visa and Mastercard. Far, far, far below them, American Express (AMEX) and Discover operate around the edges of that duopoly. As of the end of 2022, Visa and Mastercard’s networks process about 84 percent of all cards in circulation, 76 percent of the total purchase volume, and hold 69 percent of the total outstanding balance across all credit card networks. Capital One’s best case for the merger being procompetitive is that it can become a viable third competitor to those two card processing behemoths. On its face, this seems like a reasonable point, but the mechanics of how it might work are rather fuzzy.

If and when Capital One moves their cards onto the Discover network fully, they will no longer have to pay processing fees to Visa and Mastercard. (It turns out that Capital One represents a much larger share of the total cards of the Mastercard payment processing network). No longer having to pay for those fees is the headline cost saving measure in the deal, but there are potentially others. The merged company may be able to leverage economies of scale to reduce marketing, administrative, or customer service costs as well. So the merged firm may be able to reduce merchant swipe fees or interest rates for cardholders because of those savings. But would they? It’s hard to see a good reason for them to, absent some kind of binding obligation.

Perhaps the merged firm would want to compete more aggressively against Visa and Mastercard for merchants. But cutting merchant fees seems like a pretty naive reading of how credit card purchases work. Discover is already accepted at the overwhelming majority of American retailers. Because most merchants will accept Visa, Mastercard, Discover, and AMEX in the status quo, it’s difficult to picture the merged firm providing a deal so sweet that merchants would proactively encourage using cards on the Discover network over others, especially given the potential risk of losing customers who hold other cards. The merged firm would have to offer exceptionally low fees to entice merchants to proactively discourage using other card networks. Maybe they can get some merchants to offer a small discount for using cards on their network, but to accomplish that at a scale necessary to dent Visa’s and Mastercard’s omnipresence is difficult to imagine.

But there’s also a sneaky reason to expect that the merger might result in some higher merchant fees. As the American Economic Liberties Project’s Shahid Naeem said, the proposed deal is “an end-run around the Durbin Amendment and will raise fees for American businesses and consumers.” The Durbin Amendment is a component of the Dodd-Frank Act that caps transactions on debit card transaction fees, which merchants pay to the debit card issuers, at $0.21. However there are two built-in exceptions; (1) for debit issuers with less than $10 million in assets; and (2) as Marc Rubenstein pointed out, for Discover, by name. And Capital One has been clear that they want to move all their debit cards over to Discover’s network, which could make all Capital One debit cards eligible for higher fees to merchants.

Moreover, we already have a case study of how a single firm acting as issuer and processor might pan out: American Express already operates as a vertically integrated card issuer-payment processor, and AMEX charges higher merchant fees than Visa or Mastercard. So we shouldn’t expect vertical integration to automatically result in reduced merchant fees.

Be Skeptical of Purported Benefits to Cardholders

Likewise the merged firm could pass along any savings from avoided processing fees to cardholders in the form of lower interest rates. But there’s not much reason to expect that either: Recall that the horizontal aspect of the merger places upward pressure on rates for subprime customers. Any efficiencies flowing from reduced processing costs would have to overcome that upward price pressure.

The issue with any arguments about passing savings from processing costs onto cardholders is that they misunderstand the mechanism by which interest rates are set. Interest rates, both on credit cards and other types of loans, are primarily a function of the cost of borrowing at a given time (the “Prime rate”) plus a markup (the “APR margin”). The cost of borrowing is largely dependent on where the Fed sets interest rates. Hence, processing costs do not tend to enter the pricing calculus for annual credit card interest rates (which are invariant to the number of transactions). Further, a recent report from the CFPB shows that larger card issuers charge 8-10 percent higher interest rates than smaller credit card issuers, suggesting that cost efficiency actually results in higher interest rates for cardholders, not lower. The base interest rate controlled by the Fed is exogenous to all of this; the only question is how much of a premium the lender will charge.

Based on that finding, there are a couple of reasons why the merged firm would be likely to keep premiums over the Fed rates (and hence credit card interest rates) generally high, rather than pass savings on to consumers. To start, the emphasis on subprime lending creates more reason for higher markups; subprime borrowers are considered riskier, so they usually have to pay more to borrow to cover the increased odds of missing repayment. Additionally, because subprime lenders have more limited choices and because that’s the market segment Discover and Capital One both target, the merged firm’s share of subprime credit card issuing will likely require less competition than prime credit card issuing, allowing them to offer worse borrowing terms.

Be Skeptical of Other Purported Merger Benefits

Capital One further claims that the merger would make the combined firm a more potent competitor to Visa and Mastercard, potentially causing the two behemoths to reduce their own merchant fees. But this dynamic is frustrated for three reasons: built-in advantages to Visa’s and Mastercard’s business models, friction in transferring cards onto the Discover network, and disproportionate impacts on Mastercard and Visa that might actually leave only one dominant card processor.

First, Visa and Mastercard partner with lots (like lots and lots) of financial institutions rather than issuing their own cards. And that could give them a lot of advantages over Capital One/Discover. For one thing, people shop around for credit cards to varying extents. Some people look for cards with no annual fees, others make selections based off of perks like airline miles, and some people just get credit cards from the institutions they frequent. Where Mastercard and Visa really get a lot of their strength is from the partner institutions that issue the cards on their networks. This includes consumer-facing banks, credit unions, and financial institutions as well as retailers. And that comes with a lot of in-built advantages. For a start, it allows Visa and Mastercard to share responsibility on offerings like customer service with the issuer. If you go to your credit union and get their Visa credit card, you don’t need to direct every question you have to a Visa call center; many times you can call your credit union and they can answer your questions. That is both convenient and it can foster a larger degree of trust in the card, especially when the issuer is something like a credit union or local bank with whom depositors have a long history.

But there’s another, possibly even stronger, advantage to the Visa/Mastercard model–people can get cards with brand-specific rewards. Imagine you’re a contractor who buys a lot of supplies from Home Depot. The idea of a card that rewards you specifically for spending money at Home Depot could be very tempting, especially because you can often apply for it on your phone right in the store. Or if you shop at Costco, you might get a Costco card. If you travel, maybe you’d like a Southwest or American Airlines rewards card. You can get a Visa or Mastercard for any of those brands and many more. Capital One could try to set up similar partnerships, but that would likely come at the expense of their own card issuing, which is and would continue to be even after the merger, the biggest part of its business.

Second, the argument that the merger will create a more potent rival to Visa and Mastercard depends on the possibility of moving many or all of the credit cards issued by Capital One onto their in-house Discover network. That can be done, but it could well be a mess. Moving significant consumer credit accounts from one payment network to another is a big undertaking and, when it’s been done in the past, has caused major issues including consumers being unable to access their accounts or experiencing a big hit to their credit rating.

Plus there’s something of a catch 22 involved in migrating credit cards from one payment network to another. If Capital One is aggressive in transferring all of its cards onto Discover, then the odds that they actually could save on lower operating costs are much better. Fees for using a payment network are a major cost for card issuers. Moving aggressively also creates more opportunities for fatal mistakes, however, like damaging customers’ credit. On the flip side, Capital One moving only a few of its cards over would give more transition time, but would require them to continue paying fees to Visa and Mastercard without truly becoming a competitor. Either route could also complicate efforts to create rewards programs that rival Visa’s and Mastercard’s programs; other companies may not be eager to participate given uncertainty around how the transfer will play out.

Finally, if Capital One moved all of its cards over to the Discover network, it could usurp about 10 percent of Visa’s transaction volume and around 25 percent of Mastercard’s (Capital One has a lot of cards on both, but Visa has a much larger pool of other issuers’ cards on its network, so Capital One represents a markedly smaller share of traffic on their network). As of 2022, Visa’s network had 385 million cards, Mastercard’s had 309 million, and Discover’s had 75 million. That means that the new distribution (assuming the transaction volume is distributed roughly evenly across cards on all the processing networks) could look like Visa with 347 million, Mastercard with 232 million, and Discover with 191 million.

If that’s how it plays out, there’s some risk that Capital One/Discover would actually cement Visa’s advantage even more. Sure, Visa loses some 39 million cards, but Mastercard, which is already the smaller of the two, loses twice that. So, more than anything, it could be that the one true rival to Visa is weakened, leading a duopoly to become a monopoly. As far as how that impacts market share, Visa would go from 46 percent to 42 percent, Mastercard would plummet from 37 percent to 28 percent, and Discover would jump from 9 percent to 23 percent (for simplicity, AMEX is being treated as exogenous), as shown in the charts below.

And if that’s how it plays out, it could give Mastercard or American Express an opening to try and merge with each other or with other payment networks (i.e. PayPal or Klarna) and pitch it as the only way to preserve any true competition with Visa. The argument there is basically two pronged. First, Mastercard and AMEX are weaker and much less competitive, so they need a leg up to survive. Second, Capital One got to merge, so shouldn’t they? This is a common tactic corporations use in concentrated markets to justify even further concentration. See, for example, airlines.

The Merger Is Likely Anticompetitive On Net

That’s a lot to digest, but broadly, there are six things that need to be kept in mind when evaluating the Capital One/Discover merger:

- The merger will have impacts across multiple types of financial products. The two biggest are credit card issuing and credit card payment processing.

- Both Capital One and Discover focus largely on subprime borrowers. That means that, even though concentration in the issuer space may not generally be an issue, it could be much worse for those with the least access to credit already.

- Even for cardholders who do not consider interest rates while selecting a card, card issuers do compete on rewards programs, security measures, annual fees, and other features that could be gutted if a company has the market share to get away with it.

- Capital One is donning a veneer of consumer champion, mostly by claiming that it will be able to compete more effectively with Visa and Mastercard.

- Capital One’s ability to compete with Mastercard and Visa is complicated by a number of factors, including built-in advantages to Visa and Mastercard’s existing partnerships and friction in transferring Capital One cards to Discover.

- Even in the event that the merger does weaken Visa and Mastercard, it would likely asymmetrically harm Mastercard, potentially making Visa even more dominant.

The proposed merger between Capital One and Discover is complicated for a lot of reasons. Both companies offer an assortment of financial services (see this handy list from US News and World Report). Consequently, the merger will send ripples throughout an array of different banking and financial markets. Yet the meat of the deal centers on credit card issuing and payment processing. Ultimately, there are a lot of reasons why claims about Capital One’s acquisition of Discover being beneficial for consumers should be taken with a grain of salt. There are a lot of antitrust concerns, whether focusing on the card issuer space or payment processing. In particular, the deal would combine two of the largest subprime credit card issuers and could lead to worse terms for subprime borrowers. On the network side, while there is some possibility that Capital One could make the Discover network competitive with Visa and Mastercard, it could just as easily flounder or even make things worse by weakening Mastercard disproportionately. Between all of these competitive harms and other issues, plus concerns around community reinvestment (a concern raised here) and other past regulatory issues (especially recent probes of Discover), this deal could cause serious harm and deserves to face rigorous scrutiny moving forward.