If I were to draft new Merger Guidelines, I’d begin with two questions: (1) What have been the biggest failures of merger enforcement since the 1982 revision to the Merger Guidelines?; and (2) What can we do to prevent such failures going forward? The costs of under-enforcement have been large and well-documented, and include but are not limited to higher prices, less innovation, lower quality, greater inequality, and worker harms. It’s high time for a course correction. But do the new Merger Guidelines, promulgated by Biden’s Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC), do the trick?

Two Recent Case Studies Reveal the Problem

Identifying specific errors in prior merger decisions can inform whether the new Guidelines will make a difference. Would the Guidelines have prevented such errors? I focus on two recent merger decisions, revealing three significant errors in each for a total of six errors.

The 2020 approval of the T-Mobile/Sprint merger—a four-to-three merger in a highly concentrated industry—was the nadir in the history of merger enforcement. Several competition economists, myself included, sensed something was broken. Observers who watched the proceedings and read the opinion could fairly ask: If this blatantly anticompetitive merger can’t be stopped under merger law and the existing Merger Guidelines, what kind of merger can be stopped? Only mergers to monopoly?

The district court hearing the States’ challenge to T-Mobile/Sprint committed at least three fundamental errors. (The States had to challenge the merger without Trump’s DOJ, which embraced the merger for dubious reasons beyond the scope of this essay.) First, the court gave undue weight to the self-serving testimony of John Legere, T-Mobile’s CEO, who claimed economies from combining spectrum with Sprint, and also claimed that it was not in T-Mobile’s nature to exploit newfound market power. For example, the opinion noted that “Legere testified that while T-Mobile will deploy 5G across its low-band spectrum, that could not compare to the ability to provide 5G service to more consumers nationwide at faster speeds across the mid-band spectrum as well.” (citing Transcript 930:23-931:14). The opinion also noted that:

T-Mobile has built its identity and business strategy on insulting, antagonizing, and otherwise challenging AT&T and Verizon to offer pro-consumer packages and lower pricing, and the Court finds it highly unlikely that New T-Mobile will simply rest satisfied with its increased market share after the intense regulatory and public scrutiny of this transaction. As Legere and other T-Mobile executives noted at trial, doing so would essentially repudiate T-Mobile’s entire public image. (emphasis added) (citing Transcript at 1019:18-1020:1)

In the court’s mind, the conflicting testimony of the opposing economists cancelled each other out—never mind such “cancelling” happens quite frequently—leaving only the CEO’s self-serving testimony as critical evidence regarding the likely price effects. (The States’ economic experts were the esteemed Carl Shapiro and Fiona Scott Morton.) It bears noting that CEOs and other corporate executives stand to benefit handsomely from the consummation of a merger. For example, Activision Blizzard Inc. CEO Bobby Kotick reportedly stands to reap more than $500 million after Microsoft completes its purchase of the video game publishing giant.

Second, although the primary theory of harm in T-Mobile/Sprint was that the merger would reduce competition for price-sensitive customers of prepaid service, most of whom live in urban areas, the court improperly credited speculative commitments to “provide 5G service to 85 percent of the United States rural population within three years.” Such purported benefits to a different set of customers cannot serve as an offset to the harms to urban consumers who benefited from competition between the only two facilities-based carriers that catered to prepaid customers.

Third, the court improperly embraced T-Mobile’s proposed remedy to lease access to Dish at fixed rates—a form of synthetic competition—to restore the loss in facilities-based competition. Within months of the consummated merger, the cellular CPI ticked upward for the first time in a decade (save a brief blip in 2016), and T-Mobile abandoned its commitments to Dish.

The combination of T-Mobile/Sprint represented the elimination of actual competition across two wireless providers. In contrast, Facebook’s acquisition of Within, maker of the most popular virtual reality (VR) fitness app on Facebook’s VR platform, represented the elimination of potential competition, to the extent that Facebook would have entered the VR fitness space (“de novo entry”) absent the acquisition. In disclosure, I was the FTC’s economic expert. (I commend everyone to read the critical review of the new Merger Guidelines by Dennis Carlton, Facebook’s expert, in ProMarket, as well as my thread in response.) The district court sided with the FTC on (1) the key legal question of whether potential competition was a dead letter (it is not), (2) market definition (VR fitness apps), and (3) market concentration (dominated by Within). Yet many observers strangely cite this case as an example of the FTC bringing the wrong cases.

Alas, the court did not side with the FTC on the key question of whether Facebook would have entered the market for VR fitness apps de novo absent the acquisition. To arrive at that decision, the court made three significant errors. First, as Professor Steve Salop has pointed out, the court applied the wrong evidentiary standard for assessing the probability of de novo entry, requiring the FTC to show a probability of de novo entry in excess of 50 percent. Per Salop, “This standard for potential entry substantially exceeds the usual Section 7 evidentiary burden for horizontal mergers, where ‘reasonable probability’ is normally treated as a probability lower than more-likely-than-not.” (emphasis in original)

Second, the court committed an error of statistical logic, by crediting the lack of internal deliberations in the two months leading up to Facebook’s acquisition announcement in June 2021 as evidence that Facebook was not serious about de novo entry. Three months before the announcement, however, Facebook was seriously considering a partnership with Peloton—the plan was approved at the highest ranks within the firm. Facebook believed VR fitness was the key to expanding its user base beyond young males, and Facebook had entered several app categories on its VR platform in the past with considerable success. Because de novo entry and acquisition are two mutually exclusive entry paths, it stands to reason that conditional on deciding to enter via acquisition, one would expect to see a cessation of internal deliberation on an alternative entry strategy. After all, an individual standing at a crossroads would consider alternative paths, but upon deciding which path to take and embarking upon it, the previous alternatives become irrelevant. Indeed, the opinion even quoted Rade Stojsavljevic, who manages Facebook’s in-house VR app developer studios, testifying that “his enthusiasm for the Beat Saber–Peloton proposal had “slowed down” before Meta’s decision to acquire Within,” indicating that the decision to pursue de novo entry was intertwined with the decision to entry via acquisition. In any event, the relevant probability for this potential competition case was the probability that Facebook would have entered de novo in the absence of the acquisition. And that relevant probability was extremely high.

Third, like the court in T-Mobile/Sprint, the district court again credited the self-serving testimony of Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, who claimed that he never intended to enter VR fitness apps de novo. For example, the court cited Mr. Zuckerberg’s testimony that “Meta’s background and emphasis has been on communication and social VR apps,” as opposed to VR fitness apps. (citing Hearing Transcript at 1273:15–1274:22). The opinion also credited the testimony of Mr. Stojsavljevic for the proposition that “Meta has acquired other VR developers where the experience requires content creation from the developer, such as VR video games, as opposed to an app that hosts content created by others.” (citing Hearing Transcript at 87:5–88:2). Because this error overlaps with one of the three errors identified in the T-Mobile/Spring merger, I have identified five distinct errors (six less one) needing correction by the new Merger Guidelines.

Although the court credited my opinion over Facebook’s experts on the question of market definition and market concentration, the opinion did not cite any economic testimony (mine or Facebook’s experts) on how to think about the probability of entry absent the acquisition.

The New Merger Guidelines

I raise these cases and their associated errors because I want to understand whether the new Merger Guidelines—thirteen guidelines to be precise—will offer the kind of guidance that would prevent a future court from repeating the same (or similar) errors. In particular, would either the T-Mobile/Sprint or Facebook/Within decision (or both) have been altered in any significant way? Let’s dig in!

The New Guidelines reestablish the importance of concentration in merger analysis. The 1982 Guidelines, by contrast, sought to shift the emphasis from concentration to price effects and other metrics of consumer welfare, reflecting the Chicago School’s assault on the structural presumption that undergirded antitrust law. For several decades prior to the 1980s, economists empirically studied the effect of concentration on prices. But as the consumer welfare standard became antitrust’s north star, such inquiries were suddenly considered off-limits, because concentration was deemed to be “endogenous” (or determined by the same factors that determine prices), and thus causal inferences of concentration’s effect on price were deemed impossible. This was all very convenient for merger parties.

Guideline One states that “Mergers Should Not Significantly Increase Concentration in Highly Concentrated Markets.” Guideline Four states that “Mergers Should Not Eliminate a Potential Entrant in a Concentrated Market,” and Guideline Eight states that “Mergers Should Not Further a Trend Toward Concentration.” By placing the word “concentration” in three of thirteen principles, the agencies make it clear that they are resuscitating the prior structural presumption. And that’s a good thing: It means that merger parties will have to overcome the presumption that a merger in a concentrated or concentrating industry is anticompetitive. Even Guideline Six, which concerns vertical mergers, implicates concentration, as “foreclosure shares,” which are bound from above by the merging firms’ market share, are deemed “a sufficient basis to conclude that the effect of the merger may be to substantially lessen competition, subject to any rebuttal evidence.” The new Guidelines restore the original threshold Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 1,800 and delta HHI of 100 to trigger the structural presumption; that threshold had been raised to an HHI of 2,500 and a change in HHI of 200 in the 2010 revision to the Guidelines.

This resuscitation of the structural presumption is certainly helpful, but it’s not clear how it would prevent courts from (1) crediting self-serving CEO testimony, (2) embracing bogus efficiency defenses, (3) condoning prophylactic remedies, (4) committing errors in statistical logic, or (5) applying the wrong evidentiary standard for potential competition cases.

Regarding the proper weighting of self-serving employee testimony, error (1), Appendix 1 of the New Guidelines, titled “Sources of Evidence,” offers the following guidance to courts:

Across all of these categories, evidence created in the normal course of business is more probative than evidence created after the company began anticipating a merger review. Similarly, the Agencies give less weight to predictions by the parties or their employees, whether in the ordinary course of business or in anticipation of litigation, offered to allay competition concerns. Where the testimony of outcome-interested merging party employees contradicts ordinary course business records, the Agencies typically give greater weight to the business records. (emphasis added)

If heeded by judges, this advice should limit the type of errors we observed in T-Mobile/Sprint and Facebook/Within, with courts crediting the self-serving testimony by CEOs and other high-ranking employees.

Regarding the embrace of out-of-market efficiencies, error (2), Part IV.3 of the New Guidelines, in a section titled “Procompetitive Efficiencies,” offers this guidance to courts:

Merging parties sometimes raise a rebuttal argument that, notwithstanding other evidence that competition may be lessened, evidence of procompetitive efficiencies shows that no substantial lessening of competition is in fact threatened by the merger. When assessing this argument, the Agencies will not credit vague or speculative claims, nor will they credit benefits outside the relevant market. (citing Miss. River Corp. v. FTC, 454 F.2d 1083, 1089 (8th Cir. 1972)) (emphasis added)

Had this advice been heeded, the court in T-Mobile/Sprint would have been foreclosed from crediting any purported merger-induced benefits to rural customers as an offset to the loss of competition in the sale of prepaid service to urban customers.

Regarding the proper treatment of prophylactic remedies offered by merger parties, error (3), footnote 21 of the New Guidelines state that:

These Guidelines pertain only to the consideration of whether a merger or acquisition is illegal. The consideration of remedies appropriate for otherwise illegal mergers and acquisitions is beyond its scope. The Agencies review proposals to revise a merger in order to alleviate competitive concerns consistent with applicable law regarding remedies. (emphasis added)

While this approach is very principled, the agencies cannot hope to cure a current defect by sitting on the sidelines. I would advise saying something explicit about remedies, including mentioning the history of their failures to restore competition, as Professor John Kwoka documented so ably in his book Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies (MIT Press 2016).

Finally, regarding courts’ committing errors in statistical logic or applying the wrong evidentiary standard for potential competition cases, errors (4) and (5), the New Merger Guidelines devote an entire guideline (Guideline Four) to potential competition. Guideline Four states that “the Agencies examine (1) whether one or both of the merging firms had a reasonable probability of entering the relevant market other than through an anticompetitive merger.” Unfortunately, there is no mention that reasonable probability can be satisfied at less than 50 percent, per Salop, and the agencies would be wise to add such language in the Merger Guidelines. In defining “reasonable probability,” the Guidelines state that evidence that “the firm has successfully expanded into other markets in the past or already participates in adjacent or related markets” constitutes “relevant objective evidence” of a reasonable probably. In making its probability assessment, the court in Facebook/Within did not credit Facebook’s prior de novo entry in other app categories on Facebook’s VR platform. The Guidelines also state that “Subjective evidence that the company considered organic entry as an alternative to merging generally suggests that, absent the merger, entry would be reasonably probable.” Had it heeded this advice, the court would have ignored, when assessing the probability of de novo entry absent the merger, the fact that Facebook did not mention the Peloton partnership two months prior to the announcement of its acquisition of Within.

A Much Needed Improvement

In summary, I conclude that the new Merger Guidelines offer precisely the kind of guidance that would have prevented the courts in T-Mobile/Sprint and in Facebook/Within from committing significant errors. The additional language suggested here—taking a firm stance on remedies and defining reasonable probability—is really fine-tuning. While this review is admittedly limited to these two recent cases, the same analysis could be undertaken with respect to a broader array of anticompetitive mergers that have approved by courts since the structural presumption came under attack in 1982. The agencies should be commended for their good work to restore the enforcement of antitrust law.

The Federal Trade Commission’s scrutiny of Microsoft’s acquisition of game producer Activision-Blizzard did not end as planned. Judge Jacqueline Scott Corley, a Biden appointee, denied the FTC’s motion for preliminary injunction, ruling that the merger was in the public interest. At the time of this writing, the FTC has pursued an appeal of that decision to the Ninth Circuit, identifying numerous reversible legal errors that the Ninth Circuit will assess de novo.

But even critics of Judge Corley’s opinion might find agreement on one aspect: the relative lack of enforcement against anticompetitive vertical mergers in the past 40+ years. As Corley’s opinion correctly observes, United States v. AT&T Inc, 916 F.3d 1029 (D.C. Circuit 2019), is the only court of appeals decision addressing a vertical merger in decades. Absent evolution of the law to account for, among other recent phenomena, the unique nature of technology-enabled content platforms, the starting point for Corley’s opinion is misplaced faith in case law that casts vertical mergers as inherently pro-competitive.

As with horizontal mergers, the FTC and Department of Justice have historically promulgated vertical merger guidelines that outline analytical techniques and enforcement policies. In 2021, the Federal Trade Commission withdrew the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines, with the stated intent of avoiding industry and judicial reliance on “unsound economic theories.” In so doing, the FTC committed to working with the DOJ to provide guidance for vertical mergers that better reflects market realities, particularly as to various features of modern firms, including in digital markets.

The FTC’s challenge to Microsoft’s proposed $69 billion acquisition of Activision, the largest proposed acquisition in the Big Tech era, concerns a vertical merger in both existing and emerging digital markets. It involves differentiated inputs—namely, unique content for digital platforms that is inherently not replaceable. The FTC’s theories of harm, Judge Corley’s decision, and the now-pending appeal to the Ninth Circuit provide key insights into how the FTC and DOJ might update the Vertical Merger Guidelines to stem erosion of legal theories that are otherwise ripe for application to contemporary and emerging markets.

Beware of must-have inputs

In describing a vertical relationship, an “input” refers to goods that are created “upstream” of a distributor, retail, or manufacturer of finished goods. Take for instance the production and sale of tennis shoes. In the vertical relationship between the shoe manufacturer and the shoe retailer, the input is the shoe itself. If the shoe manufacturer and shoe retailer merge, that’s called a vertical merger—and the input in this example, tennis shoes, is characteristic of a replaceable good that vertical merger scrutiny has conventionally addressed. If such a merger were to occur and the newly-merged firm sought to foreclose rival shoe retailers from selling its shoes, rival shoe retailers would likely seek an alternative source for tennis shoes, assuming the availability of such an alternative.

When it comes to assessing vertical mergers in digital content markets, not all inputs are created equal. To the contrary, online platforms, audio and video streaming platforms, and—in the case of Microsoft’s proposed acquisition of Activision—gaming platforms all rely on unique intellectual property that cannot simply be replicated if a platform’s access to that content is restricted. The ability to foreclose access to differentiated content that flows from the merger of a content creator and distributor creates a heightened concern of anticompetitive effects, because rivals cannot readily switch to alternatives to the foreclosed product. This is particularly true when the foreclosed content is extremely popular or “must-have,” and where the goal of the merged firm is to steer consumers toward the platform where it is exclusively available. (See also Steven Salop, “Invigorating Vertical Merger Enforcement,” 127 Yale L.J. 1962 (2018).)

The 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines fall short in their analysis of mergers involving highly differentiated products. The guidelines emphasize that vertical mergers are pro-competitive when they eliminate “double marginalization,” or mark-ups that independent firms claim at different levels of the distribution chain. For example, when game consoles purchase content from game developers, they may decide to add a mark-up on that content before offering it for consumer consumption. (In the real world of predatory pricing and cross-subsidization, the incentive to add such a mark-up is a more complex business calculation.) Theoretically, the elimination of those markups creates an incentive to lower prices to the end consumer.

But this narrow focus on elimination of double marginalization—and theoretical downward price pressure for consumers—ignores how the reduction in competition among downstream retailers for access to those inputs can also degrade the quality of the input. Let’s take Microsoft-Activision as an example. As an independent firm, Activision creates games and downstream consoles engage in some form of competition to carry those games. When consoles compete on terms to carry Activision games, the result to Activision includes greater investment in game development and higher quality games. When Microsoft acquires Activision, that downstream competition for exclusive or first-run access to Activision’s games is diminished. Gone is the pro-competitive pressure created by rival consoles bidding for exclusivity, as is the incentive for Activision to innovate and demand greater third-party investment in higher quality games.

Emphasizing the pro-competitive effects of eliminating double marginalization—even if that means lower prices to consumers—only provides half of the picture, because consumers will likely be paying for lower quality games. Previous iterations of the Vertical Merger Guidelines emphasize the consumer benefits of eliminating double marginalization, but they stop short of assessing the countervailing harms of mergers involving differentiated inputs. They should be updated accordingly.

Partial foreclosure will suffice

During the evidentiary hearings in the Northern District of California, the FTC repeatedly pushed back against the artificially high burden of having to prove that Microsoft had an incentive to fully foreclose access to Activision games. In the midst of an exchange during the FTC’s closing arguments, FTC’s counsel put it directly: “I don’t want to just give into the full foreclosure theory. That’s another artificially high burden that the Defendants have tried to put on the government.” And yet, in her decision, Judge Corley conflates the analysis for both full and partial foreclosure, writing, “If the FTC has not shown a financial incentive to engage in full foreclosure, then it has not shown a financial incentive to engage in partial foreclosure.”

Although agencies have acknowledged that the incentive to partially foreclose may exist even in the absence of total foreclosure (see, for instance, the FCC’s 2011 Order regarding the Comcast-NBCU vertical transaction), the Vertical Merger Guidelines do not make any such distinction. Again, that incomplete analysis hinges in part on the failure to distinguish between types of inputs. Take for instance a producer of oranges merging with a firm that makes orange juice. Theoretically, the merged firm might fully foreclose access to oranges to rival orange juice makers, who may then go in search for alternative sources of oranges. Or the merged firm might supply lower quality produce to rival firms, which may again send it in search of an alternative source.

But a merged firm’s ability and incentive to foreclose looks different when foreclosure takes the subtler form of investing less in the functionality of game content with a gaming console, subtly degrading game features, or adding unique features to the merged firm’s platforms in ways that will eventually drive more astute gamers to the merged firm (even though the game in question is technically still available on rival consoles). Such eventualities are perhaps easier to imagine in the context of other content platforms—for example, if news content were less readable on one social media platform than another. When a merged firm has unilateral control over those subtle design and development decisions, the ability and incentive to engage in more subtle forms of anticompetitive partial foreclosure is more likely and predictable.

In finding that Microsoft would not have a financial incentive to fully foreclose access to Activision games, Judge Corley’s analysis hinges on a near-term assessment of Microsoft’s financial incentive to elicit game sales by keeping games on rival consoles. (Never mind that Microsoft is a $2.5 trillion corporation that can afford near-term losses in service of its longer-view monopoly ambitions.) Regardless, a theory of partial foreclosure does not mean that Microsoft must forgo independent sales on rival consoles to achieve its ambitions. To the contrary, partial foreclosure would still allow users to purchase and play games on rival consoles. But it also allows for Microsoft’s incentive to gradually encourage consumers to use its own console or game subscription service for better game play and unique features.

Finally, Judge Corley’s analysis of Microsoft’s incentive to fully foreclosure is irresponsibly deferential to statements made by Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick that the merging entities would suffer “irreparable reputational harm” if games were not made available on rival consoles. Again, by conflating the incentives for full and partial foreclosure, the court ignores Microsoft’s ability to mitigate that reputational harm—while continuing to drive consumers to its own platforms—if foreclosure is only partial.

Rejecting private behavioral remedies

In a particularly convoluted passage in the district court’s order, the Court appears to read an entirely new requirement into the FTC’s initial burden of demonstrating a likelihood of success on the merits—namely, that the FTC must assess the adequacy of Microsoft’s proposed side agreements with rival consoles and third-party platforms to not foreclose access to Call of Duty. Never mind that these side agreements lack any verifiable uniformity, are timebound, and cannot possibly account for incentives for partial foreclosure. Yet, the Court takes at face value the adequacy of those agreements, identifying them as the principal evidence of Microsoft’s lack of incentive to foreclose access to just one of Activision’s several AAA games.

In its appeal to the Ninth Circuit, the FTC seizes on this potential legal error as a basis for reversal. The FTC writes, “in crediting proposed efficiencies absent any analysis of their actual market impact, the district court failed to heed [the Ninth Circuit’s] observation ‘[t]he Supreme Court has never expressly approved an efficiencies defense to a Section 7 claim.’” The FTC argues that Microsoft’s proposed remedies should only have been considered after a finding of liability at the subsequent remedy stage of a merits proceeding, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Greater Buffalo Press, Inc., 402 U.S. 549 (1971). Indeed, federal statute identifies the Commission as the expert body equipped to craft appropriate remedies in the event of a violation of the antitrust laws.

In its statement withdrawing the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines, the FTC announced it would work with the Department of Justice on updating the guidelines to address ineffective remedies. Presumably, the district court’s heavy reliance on Microsoft’s proposed behavioral remedies is catalyst enough to clarify that they should not qualify as cognizable efficiencies, at least at the initial stages of a case brought by the FTC or DOJ.

If this decision has taught us anything, it is that the agencies can’t come out with the new Merger Guidelines fast enough. In particular, those guidelines must address the competitive harms that flow from the vertical integration of differentiated content and digital media platforms. Even so, updating the guidelines may be insufficient to shift a judiciary so hostile to merger enforcement that it will turn a blind eye to brazen admissions of a merging firm’s monopoly ambitions. If that’s the case, we should look to Congress to reassert its anti-monopoly objectives.

Lee Hepner is Legal Counsel at the American Economic Liberties Project.

At some point soon, the Federal Trade Commission is very likely to sue Amazon over the many ways the e-commerce giant abuses its power over online retail, cloud computing and beyond. If and when it does, the agency would be wise to lean hard on the useful and powerful law at the core of its anti-monopoly authority.

The agency’s animating statute, the Federal Trade Commission Act and its crucial Section 5, bans “unfair methods of competition,” a phrase Congress deliberately crafted, and the Supreme Court has interpreted, to give the agency broad powers beyond the traditional antitrust laws to punish and prevent the unfair, anticompetitive conduct of monopolists and those companies that seek to monopolize industries.

Section 5 is what makes the FTC the FTC. Yet the agency hasn’t used its most powerful statute to its fullest capability for years. Today, with the world’s most powerful monopolist fully in the commission’s sights, the time for the FTC to re-embrace its core mission of ensuring fairness in the economy is now.

The FTC appears to agree. Last year, the agency issued fresh guidance for how and why it will enforce its core anti-monopoly law, and the 16-page document read like a promise to once again step up and enforce the law against corporate abuse just as Congress had intended.

Why Section 5?

The history of the Section 5—why Congress included it in the law and how lawmakers expected it to be enforced—is clear and has been spelled out in detail: Congress set out to create an expert antitrust agency that could go after bad actors and dangerous conduct that the traditional anti-monopoly law, the Sherman Act, could not necessarily reach. To do that, Congress crafted Section 5 so that the FTC could stop tactics that dominant corporations devise to sidestep competition on the merits and instead unfairly drive out their competitors. Congress gave the FTC the power to enforce the law on its own, to stop judges from hamstringing the law from the bench, as they have done to the Sherman Act.

As I’ve detailed, the Supreme Court has issued scores of rulings since the 1970s that have collectively gutted the ability of public enforcement agencies and private plaintiffs to sue monopolists for their abusive conduct and win. These cases have names—Trinko, American Express, Brooke Group, and so on—and, together, they dramatically reshaped the country’s decades-old anti-monopoly policy and allowed once-illegal corporate conduct to go unchecked.

Many of these decisions are now decades old, but they continue to have outsized effects on our ability to policy monopoly abuses. The Court’s 1984 Jefferson Parish decision, for example, made it far more difficult to successfully prosecute a tying case, in which a monopolist in one industry forces customers to buy a separate product or service. The circuit court in the government’s monopoly case against Microsoft relied heavily on Jefferson Parish in overturning the lower court’s order to break Microsoft up. More recently, courts deciding antitrust cases against Facebook, Qualcomm and Apple all relied on decades of pro-bigness court rulings to throw out credible monopoly claims against powerful defendants.

Indeed, the courts’ willingness to undermine Congress was a core concern for lawmakers when drafting and passing Section 5. Three years before Congress created the FTC, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its verdict in the government’s monopoly case against Standard Oil, breaking up the oil trust but also establishing the so-called “rule of reason” standard for monopoly cases. That standard gave judges the power to decide if and when a monopoly violated the law, regardless of the language of, or democratic intent behind, the Sherman Act. Since then, the courts have marched the law away from its goal of constraining monopoly power, case by case, to the point that bringing most monopolization cases under the Sherman Act today is far more difficult than it should be, given the simple text of the law and Congress’ intent when it wrote, debated, and passed the act.

That’s the beauty and the importance of Section 5. Congress knew that the judicial constraints put on the Sherman Act meant it could not not reach every monopolistic act in the economy. That’s now truer than ever. Section 5 can stop and prevent unfair, anticompetitive acts without having to rely on precedent built up around the Sherman Act. It’s a separate law, with a separate standard and a separate enforcement apparatus. What’s more, the case law around Section 5 has reinforced the agency’s purview. In at least a dozen decisions, the Supreme Court has made clear that Congress intended for the law to reach unfair conduct that falls outside of the reach of the Sherman Act.

So the law is on solid footing, and after decades of sidestepping the job Congress charged it to do, the FTC appears ready to once again take on abuses of corporate power. And not a moment too soon. After decades of inadequate antitrust enforcement, unfairness abounds, particularly when it comes to the most powerful companies in the economy. Amazon perches atop that list.

A Recidivist Violator of Antitrust Laws

Investigators and Congress have repeatedly identified Amazon practices that appear to violate the spirit of the antitrust laws. The company has a long history of using predatory pricing as a tactic to undermine its competition, either as a means of forcing companies to accept its takeover offers, as it did with Zappos and Diapers.com, or simply as a way to weaken vendors or take market share from competing retailers, especially small, independent businesses. Lina Khan, the FTC’s chair, has called out Amazon’s predatory pricing, both in her seminal 2017 paper Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, and when working for the House Judiciary Committee during its big tech monopoly investigation.

Under the current interpretation of predatory pricing as a violation of the Sherman Act, a company that priced a product below cost to undercut a rival must successfully put that rival out of business and then hike up prices to the point that it can recoup the money it lost with its below-cost pricing. Yet with companies like Amazon—big, rich, with different income streams and sources of capital—it might never need to make up for its below-cost pricing by hiking up prices on any one specific product, let alone the below-cost product. Indeed, as Jeff Bezos’s vast fortune can attest, predatory pricing can generate lucrative returns simply by sending a company’s stock price soaring as it rapidly gains market share.

If Amazon wants to sell products from popular books to private-label batteries at a loss, it can. Amazon makes enormous profits by taxing small businesses on its marketplace platform and from Amazon Web Services. It can sell stuff below cost forever if it wants to–a clearly unfair method of competing with any other single-product business–all while avoiding prosecution under the judicially weakened Sherman Act. Section 5 can and should step in to stop such conduct.

Amazon’s marketplace itself is another monopolization issue that the FTC could and should address with Section 5. The company’s monopoly online retail platform has become essential for many small businesses and others trying to reach customers. To wit, the company controls at least half of all online commerce, and even more for some products. As an online retail platform, Amazon is essential, suggesting it should be under some obligation to allow equal access to all users at minimal cost. Of course, that’s not what happens; as my organization has documented extensively, Amazon’s captured third-party sellers pay a litany of tolls and fees just to be visible to shoppers on the site. Amazon’s tolls can now account for more than half of the revenues from every sale a small business makes on the platform.

The control Amazon displays over its sellers mirrors the railroad monopolies of yesteryear, which controlled commerce by deciding which goods could reach buyers and under what terms. Antitrust action under the Sherman Act and legislation helped break down the railroad trusts a century ago. But if enforcers were to declare Amazon’s marketplace an essential facility today, the path to prosecution under the Sherman Act would be difficult at best.

Section 5’s broad prohibition of unfair business practices could prevent Amazon’s anticompetitive abuses. It could ban Amazon from discriminating against companies that sell products on its platform that compete with Amazon’s own in-house brands, or stop it from punishing sellers that refuse to buy Amazon’s own logistics and advertising services by burying their products in its search algorithm. The FTC could potentially challenge such conduct under the Sherman Act, as a tying case, or an essential facilities case. But again, the pathway to winning those cases is fraught, even though the conduct is clearly unfair and anticompetitive. If Amazon’s platform is the road to the market, then the rules of that road need to be fair for all. Section 5 could help pave the way.

These are just a few of the ways we could see the FTC use its broad authority under Section 5 to take on some of Amazon’s most egregious conduct. If I had to guess, I imagine the FTC in a potential future Amazon lawsuit will likely charge the company under both the Sherman Act and the FTC Act’s Section 5 for some conduct it feels the traditional anti-monopoly statute can reach, and will rely solely on Section 5 for conduct that it believes is unfair and anticompetitive, but beyond the scope of the Sherman Act in its current, judicially constrained form. For example, while the FTC could potentially use the Sherman Act to address Amazon’s decision to tie success on its marketplace to its logistics and advertising services, the agency’s statement makes clear that Section 5 has been and can be used to address “loyalty rebates, tying, bundling, and exclusive dealing arrangements that have the tendency to ripen into violations of the antitrust laws by virtue of industry conditions and the respondent’s position within the industry.”

Might this describe Amazon’s conduct? Very possibly, but that will ultimately be up to the FTC to decide. Suing Amazon under both statutes would invite the court to make better choices around the Sherman Act that are more critical of monopoly abuses, and help develop the law so that the FTC can eagerly embark on its core mission under Section 5: to help ensure markets are fair for all.

Ron Knox is a Senior Researcher and Writer for ILSR’s Independent Business Initiative.

Paradigm change is hard. It took over a year to overcome significant ridicule from neoliberal economists and pundits for the evidence to be so compelling as to flip the consensus on the causes of inflation. Business press outlets from the Wall Street Journal to Bloomberg to Business Insider now perceive what some heterodox economists have recognized for a while—that companies in concentrated industries were exploiting an inflationary environment to hike prices in excess of any cost increases they were incurring. (Alas, The Economist refuses to see the light.) Even Biden’s director of the National Economic Council, Lael Brainard, refers to this bout of inflation as a “price-price spiral, whereby final prices have risen by more than the increases in input prices.”

It’s hard to assign credit for flipping the script, but a few brave economists deserve mention. Isabella Weber, an economist at the University of Massachusetts, published a provocative article, co-authored with Evan Wasner, titled “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?” They explain how firms with market power only engage in price hikes if they expect their competitors to follow, which requires an implicit agreement that can be coordinated by sector-wide cost shocks and supply bottlenecks.

Josh Bivens of Economic Policy Institute debunked the neoliberal claim that wage demand was driving inflation, showing instead that corporate profit was responsible for more than one third of the price growth. Mike Konzcal and Niko Lusiani of the Roosevelt Institute demonstrated that U.S. firms that increased markups in 2021 the most were those with the higher mark-ups prior to the economic shocks, an indication that concentration was facilitating coordination. (If one were to expand the list of thought influencers beyond economists, you’d have to start with Lindsay Owens of the Groundwork Collaborative, who has been analyzing what CEOs say on earnings calls since the onset of inflation.)

With the new consensus, we need think creatively about attacking inflation. We have more than one tool at our disposal. Rate hikes might ultimately slow inflation, but at enormous social costs, as that mechanism requires putting people out of work so they have less money to spend. What’s worse, rate hikes are regressive, with the most vulnerable among us bearing the largest costs. Solving the inflationary puzzle calls for a scalpel not a chainsaw: We need to identify the industries that contribute the most to inflation (e.g. rental, electricity, certain foods), and then tailor remedies that attack inflation at its source. To use one analogy, it wouldn’t make sense to bulldoze a house because a fire was burning in one room. You’d find that room and put out the fire. I am calling for seven policies in particular.

(1) More Bully Pulpit. The President should use the bully pulpit more—recall JFK’s turning back steel price hikes in 1962. Biden called out junk fees in his state of the union address, causing airlines to remove unwarranted fees for families sitting together. Clearly, Biden can’t hold a press conference about a misbehaving industry daily. But he has not come close to tapping this well.

(2) More Congressional Hearings. Congress should hold hearings to call executives to account for price gouging. Although Congress has held hearings with experts, they have yet to summon the CEOs of industries employing massive price hikes, seemingly in coordination—as if they were some tacit agreement to raise prices in unison. I’d start by calling the CEOs of the packaged food makers, PepsiCo, Unilever, and Nestlé, who bragged last week to investors about record profits, massive price hikes, and enduring pricing power.

(3) The FTC to the Rescue. The FTC should investigate firms for announcing current or future price hikes (or capacity reductions) during earnings calls under the agency’s unique Section 5 authority to police “invitations to collude.” These cases of “tacit collusion” are much harder to prosecute under the Sherman Act. If the FTC were to publicly announce an investigation into a firm or industry—airlines (admittedly outside the FTC’s jurisdiction) or retail would be a good place to start—it would force CEOs economywide to exercise more caution about sharing competitively sensitive information on earnings calls.

(4) Limits on Concentrated Holdings: The cost of shelter makes up a significant share of the core CPI. Cities or states should move to limit the holdings of any individual firm within a given census tract. My OECD paper, co-authored with Jacob Linger and Ted Tatos, showed the nexus between rental inflation and concentration in Florida. A natural cap for a single owner would be five or ten percent of all rental properties in a neighborhood. Raising interest rates, our default anti-inflation tool, perversely puts home ownership out of reach of millions of families, driving them to the rental markets, which bids up rental rates, which is one of the primary drivers of inflation.

(5) Price Controls Should Be on the Table. Price controls are the ugly stepsister in economics. But when backed by a public campaign, they have proven to be effective. Congress imposed price caps for insulin copays in the Inflation Reduction Act, but only for those patients covered by Medicare. Insulin makers, beginning with Eli Lilly, saw the writing on the wall, and voluntarily imposed the $35 cap on all patients. So long as caps are sparingly used in mature industries, the standard investment concerns of economists should be mitigated. The lesson from insulin is that the mere talk of price controls can induce an industry to temper their enthusiasm for price hikes.

(6) Government Provisioning. The threat of government provisioning is another lever that may force private industry to behave. To wit, California offered a $50 million contract to makes its own insulin, which coincided with Eli Lilly, Sanofi and Novo Nordisk preemptively reducing their prices. This playbook could be used in other industries where inflation remains stubbornly high. We can anticipate libertarians screaming “socialism,” but if the cost of inaction is more rate hikes and unemployment, I’d take the libertarian jeers any day.

(7) Fix Antitrust Law. Congress should amend the Sherman Act to give the DOJ, state attorneys general, and private enforcers a better shot at policing tacit collusion among firms in concentrated industries. Courts have implicitly adopted the notion that oligopolistic interdependence is just as likely to achieve prices inflated over competitive conditions as agreement, and so “merely” alleging or putting forward evidence of parallel pricing, excess capacity, and artificially inflated prices is insufficient to prove agreement under Section 1. But why should we presume that it is just as easy to maintain artificially inflated prices tacitly than through agreement?

Congress should flip the presumption. In particular, Section 1 of the Sherman Act should be amended so that the following shall create a presumption of agreement: Evidence of parallel pricing accompanied by evidence of (a) inter-firm communications containing competitively sensitive information, or (b) other actions that would be against the unilateral interests of firms not otherwise colluding, or (c) prices exceeding those that would be predicted by fundamentals of supply or demand. Moreover, the Sherman Act should be amended to permit courts to sanction corporate executives who participated in any price-fixing conspiracy upon a guilty verdict, by barring the executives from working in the industries in which they broke the law, either indefinitely or for a period of time.

Industrial organization gatekeepers like to poo-poo the idea of using competition tools to attack inflation, noting that antitrust moves too slowly. This is needlessly pessimistic. It bears noting that none of the seven remedies suggested here involve bringing a traditional antitrust case against a set of firms pursuant to the Sherman Act. The common thread that binds the first six remedies is inducing a short-run shift in industry behavior. A forced divestiture of rental properties over a holding limit would inject downward-pressure on rents in the short run. CEOs don’t want to be called out by the president or called to testify before Congress to explain their record-breaking profits attributable to massive price hikes above any cost increases. A public investigation by the FTC into invitations to collude via earnings calls would also have an immediate effect on CEOs. Nor would CEOs take lightly to being barred for life from an industry for participating in a price-fixing scheme.

The seven interventions outlined here will require an all-of-government approach. Biden should create a task force to carry out these policies and issue an executive order to signal his seriousness to other agencies. There are two paths for Biden’s legacy: Do nothing about inflation and leave it to the Fed to engineer a recession that likely ends his presidency, or grab the reins himself. With the new consensus emerging that profits (and not wage demands) are driving inflation, the time has come to change our approach.

As the frontline against illegal monopolies and deceptive corporate behavior, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a critical role to play in building an economy that works for consumers and small businesses. Since becoming FTC Chair, Lina Khan’s efforts to rein in anti-competitive behavior and protect consumers has been met with fierce resistance from powerful special interests and hostile editorials in the The Wall Street Journal.

Unfortunately, given the FTC’s role in combating unfair corporate behavior, this pushback is to be expected. I should know: I had the privilege of being an FTC commissioner, serving in both the Clinton and Bush administrations. I’ve seen fair, and unfair, criticism targeted at Republican and Democratic FTC chairs alike.

As a commissioner, I served under Chair Tim Muris, who was appointed by George W. Bush and whose aggressive stewardship of the agency resembled in many ways the current leadership of Chair Lina Khan. While at the helm of the FTC, Chair Muris pursued one of the most aggressive regulatory agendas of any Bush-appointed agency heads. His agenda was assisted by his chief of staff, Christine S. Wilson, who went on to be appointed to the FTC by Donald Trump.

Despite this history, Wilson made big news when, as part of her resignation announcement, she attacked Chair Khan’s “honesty and integrity” and accused her of “abuses of government power” and “lawlessness.” This turned many heads in Washington, particularly mine because of how detached this viewpoint was from my prior experience of serving at the FTC under Wilson’s own stewardship of the agency.

In his 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, President Biden acknowledged that “a fair, open, and competitive marketplace has long been a cornerstone of the American economy.” Unfortunately, corporate concentration has grown under both parties for many years, especially in the technology industry. It is fortunate, and past time, to see the White House, the FTC, Department of Justice, and other agencies working to swing back the pendulum and reinvigorate competition in the American economy.

Despite the ongoing crisis of corporate concentration, Ms. Wilson took objection to an antitrust policy statement the FTC adopted in November and to Chair Khan’s statements in favor of strong enforcement. I found this odd having seen up close Ms. Wilson zealously advance Chair Muris’s enforcement agenda. In office, Muris “challenged mergers in markets from ‘ice cream to pickles,’” as the Wall Street Journal once noted, including in the technology industry, where Lina Khan has devoted significant attention.

During his tenure, Muris used the power available to him as Chair on behalf of consumers and for the good of the economy. He evolved the theory behind FTC regulatory authority so he could take new action to protect consumers—like creating the DO NOT CALL registry—over frivolous legal objections by the telecommunications industry. Like Khan, he coordinated with the DOJ to ensure that they were addressing anticompetitive behavior.

Ms. Wilson claims that Chair Khan should have recused herself from a Facebook acquisition case because of opinions she had expressed as a Congressional staffer. But both a federal judge and the full Commission found no basis to these claims of impropriety, and it is clear that Chair Khan had no legal or ethical obligation to recuse in this case. FTC Commissioners including Khan, like judges, are required to set their personal opinions aside and evaluate cases on the merits, and they do. The FTC Ethics Guidelines tells commissioners to ”not work on FTC matters that affect your interests: financial, relational, or organizational.” When it comes to ethics guidelines, it doesn’t get any plainer than that, and Chair Khan’s participation in the case clearly does not violate these guidelines.

In a hyper-partisan environment, Ms. Wilson’s attacks on the FTC’s credibility appear to me as an attempt to slow antitrust enforcement and ultimately obfuscate Chair Khan’s pro-consumer agenda.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which lobbies against pro-consumer regulations, sent an open letter to Senate oversight committees demanding an investigation of “mismanagement” at the FTC, including congressional hearings. No wonder the Chamber is upset. The Biden Administration is taking the crisis of corporate concentration seriously and is taking steps to bolster antitrust and consumer protection enforcement. That’s a development American consumers should cheer, because when corporate consolidation rises, competition is inevitably diminished, leading to higher prices and fewer choices for consumers.

Fortunately, Chair Khan is building on the legacy of strong leaders like Muris to build an economy that works for consumers, not harmful monopolies. Ultimately, she will be remembered for that and not cynical, distracting attacks on her.

Sheila Foster Anthony, a FTC commissioner from 1997-2003, previously served as Assistant Attorney General for Legislation at the U.S.Department of Justice. Prior to her government service, she practiced intellectual property law in a D.C. firm.

Over the last 40 years, antitrust cases have been increasingly onerous and costly to litigate, yet if plaintiffs can prevail on one single issue, they dramatically enhance their chances of obtaining a favorable judgment. That issue is market definition.

Market definition is straightforward to explain because it’s just what it sounds like. Litigants and judges must be able to delineate the market in question in order to determine how much control a corporation exercises over it. Defining a relevant market essentially answers, depending on the conduct courts are analyzing, whether computers that run Apple’s MacOS operating system or Microsoft Windows are in the same market or, similarly, if Coca-Cola competes with Pepsi.

A corporation’s degree of control over any particular market is then typically measured by how much market share it has. In antitrust litigation, calculating a firm’s market share is the simplest and most common way to determine a firm’s ability to adversely affect market competition, including its influence over output, prices, or the entry of new firms. While the issue may seem mundane and even somewhat technocratic, defining a relevant market is the single most important determination in antitrust litigation. Indeed, many antitrust violations turn on whether a defendant has a high market share in the relevant market.

Market definition is a throughline in antitrust litigation. All violations that require a rule of reason analysis under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, such as resale price maintenance and vertical territorial restraints, require a market to be defined. All claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act require a relevant market. And all claims under Sections 3 and 7 of the Clayton Act require a relevant market to be defined.

Defining relevant markets stems from the language of the antitrust laws. Section 2 of the Sherman Act states that monopolization tactics are illegal in “any part of the trade or commerce[.]” Sections 3 and Section 7 prohibit exclusive deals and tyings involving commodities and mergers, respectively in “any line of commerce or…in any section of the country[.]” “[A]ny” “part” or “line of commerce” inherently requires some description of a market that is at issue.

As I more thoroughly described in a newly released working paper, the process of defining relevant markets has a long and winding history stemming from the inception of the Sherman Act in 1890. Between 1890 and 1944, the Supreme Court took a highly generalized approach, requiring as it stated in 1895, only a description of “some considerable portion, of a particular kind of merchandise or commodity[.]” In subsequent cases during this initial era, the Supreme Court provided little additional guidance, maintaining that litigants merely needed to provide a generalized description of “any one of the classes of things forming a part of interstate or foreign commerce.”

In 1945, after Circuit Court Judge Learned Hand found the Aluminum Company of America (commonly known as ALCOA) liable for monopolization in a landmark case, the market definition process started to become more refined, primarily focusing on how products were similar and interchangeable such that they performed comparable functions. At the same time market definition took on more complexity, antitrust enforcement exploded and courts became flooded with antitrust litigation. Given the circumstances, the Supreme Court felt that it needed to provide litigants with more structure to the antitrust laws, not only to effectuate Congress’s intent of protecting freedom of economic opportunity and preventing dominant corporations from using unfair business practices to succeed, but also to assist judges in determining whether a violation occurred. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Supreme Court repeatedly expressed its frustration that there was no formal process for litigants to help the courts define markets.

It took until 1962 for the Supreme Court to comprehensively determine how markets should be defined and bring some much-needed structure to antitrust enforcement. The process, known as the Brown Shoe methodology after the 1962 case, requires litigants to present information to a reviewing court that describes the “nature of the commercial entities involved and by the nature of the competition [firms] face…[based on] trade realit[ies].” With this information, judges are required to engage in a heavy review of the information they are presented with and make a reasonable decision that accurately reflects the actual market competition between the products and services at issue in the litigation.

Constructing a relevant market for the purposes of antitrust litigation using the Brown Shoe methodology can be made using a variety of commonly understood and accessible information sources. For example, previous markets in antitrust litigation have been constructed from reviewing consumer preferences, consumer surveys, comparing the functional capabilities of products, the uniqueness of the buyers or production facilities, or trade association data. In a series of cases between 1962 to the present, the Supreme Court has rigorously refined its Brown Shoe process to ensure both litigants and judges had sufficient guidance to define markets. Critically, in no way did the Supreme Court intend for its Brown Shoe methodology to restrict or hinder the enforcement of the antitrust laws, and the fact that the process relies on readily accessible and commonly understood information is indicative of that goal.

But 1982 was a watershed year. Enforcement officials in the Reagan administration tossed aside more than a decade of carefully crafted jurisprudence from the Supreme Court in favor of complex, unnecessary, and arbitrary tests to define a relevant market. The new test, known as the hypothetical monopolist test (HMT), which is often informed by econometric models, asks whether a hypothetical monopolist of the products under consideration could profitably raise prices over competitive levels. It is tantamount to asking how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. They primarily accomplished this economics-laden burden through the implementation of a new set of guidelines that detailed how the Department of Justice would analyze mergers, determine whether to bring an enforcement action, and how the agency would conduct certain parts of antitrust litigation, one of those aspects being the market definition process.

From the 1982 implementation of new merger guidelines to the present, judges and litigants, predominantly federal enforcers, have ignored the Brown Shoe methodology and instead have embraced the HMT and its navel-gazing estimation of angels. As a result, courts now entertain battles of econometric experts, over what should amount to a straightforward inquiry.

As scholar Louis Schwartz aptly described, the relegation of the Brown Shoe methodology and its brazen replacement with econometrics under the 1982 guidelines represented a “legal smuggling” of byzantine economic criteria into antitrust litigation.

Besides facilitating the de-economization of antitrust enforcement, abandoning the econometric process would have other notable benefits. First, relying entirely on the Brown Shoe methodology would restrict the power of judges, lawyers, and economists by making the law more comprehensible to litigants. Giving power back to litigants would contribute to making antitrust law less technocratic and abstruse and more democratically accountable. For example, in some cases, economists have great difficulty explaining their findings to judges in intelligible terms. In extreme cases, judges are required to hire their own economic experts just to decipher the material presented by the litigants. Simply stated, the law is not just for economists, judges, or lawyers; it is also for ordinary people. Discarding the econometric tests for market definition facilitates not only the understanding of antitrust law, but also how to stay within its boundaries.

Second, reverting to the Brown Shoe methodology would make antitrust law fairer and promote its enforcement. The only parties that stand to gain from employing econometric tests are the economists conducting the analysis, the lawyers defending large corporations, and corporations who wish to be shielded from the antitrust laws. Frequently charging more than a $1,000 dollars an hour, economists are also extraordinarily expensive for litigants to employ, creating an exceptionally high barrier to otherwise meritorious legal claims.

Since 1982, market definition in antitrust litigation has lingered in a highly nebulous environment, where both the econometric tests informing the HMT and the Brown Shoe methodology co-exist but with only the Brown Shoe methodology having explicit approval by the Supreme Court. Even in its highly contentious and confusing 2018 ruling in Ohio v. American Express, the Supreme Court did not mention or cite the econometric processes currently employed by courts and detailed in the merger guidelines to define relevant markets. In fact, in a brief statement, the Court reaffirmed the controlling process it developed in Brown Shoe, yet lower courts continue to cite the failure of plaintiffs to meet the requirements of the econometric market definition process as one of the primary reasons to dismiss antitrust cases. Putting it aptly, Professor Jonathan Baker has stated that the “outcome of more [antitrust] cases has surely turned on market definition than on any other substantive issue.”

While the econometric process is not the exclusive process enforcers use to define markets in antitrust litigation and is often used in conjunction with the Brown Shoe methodology, completely abandoning it is critical to de-economizing antitrust law more generally. Since the late 1970s, primarily due to the work published by Robert Bork and other Chicago School adherents, economics and economic thinking more generally have become deeply entrenched in antitrust litigation. Chicago School thought has essentially made antitrust enforcement of nearly all vertical restraints like territorial limitations per se legal, and since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has overturned many of its per se rules. Contravening controlling case law on vertical mergers, Chicago School thinking has resulted in judges viewing them as almost always benign or even beneficial and failing to condemn them by applying the antitrust laws. Dubious economic assumptions have significantly restricted antitrust liability for predatory pricing, a practice described by the Supreme Court in 1986 as “rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.” As a result, economic thinking and econometric methodologies, though running contrary to Congress’s intent, have served to undermine the enforcement of the antitrust laws. This is not to say there is no role for economists. Economists can engage in essential fact gathering activities or provide scholarly perspective on empirical data that shows how specific business conduct can adversely affect prices, output, consumer choice, or innovation. For example, economic research has found that mergers and acquisitions habitually lead to higher prices and increased corporate profit margins – repudiating the idea that mergers are beneficial for consumers. But economists have little value to add when it comes to market definition.

Reinstituting many of the overturned per se antitrust rules all but require a change of precedent from the Supreme Court, which appears highly unlikely given the ideology of most of the current justices. However, modifying the process that enforcers use to determine relevant markets does not require overcoming such a seemingly insurmountable hurdle. Ridding antitrust litigation of the econometric process would simply require enforcers, particularly those at the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, to completely abandon the process altogether in their enforcement efforts (particularly in the merger guidelines) and instead exclusively rely on the Brown Shoe methodology. Neither the law nor the jurisprudence would need to be modified to effectuate this change—although it might be helpful, before unilaterally disarming, to first explain the new policy in the agencies’ forthcoming revision to the merger guidelines.

While some judges currently ignore or dismiss the Brown Shoe methodology, were enforcers to completely abandon the econometric process for defining markets, courts effectively would have no choice but to rely on the controlling Brown Shoe process. Unlike other aspects of antitrust law, enforcement officials can and should fully embrace the controlling law, in this case Brown Shoe, and use it readily, leaving private litigants to employ the econometric process if they so chose. Nevertheless, history indicates that courts are highly deferential to the methods used by federal enforcers—especially when explicated in the merger guidelines—and private litigants would likely follow the lead of federal enforcers in deciding which method to use to define relevant markets.

Currently, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission are redoing and updating their merger guidelines. To continue facilitating the progressive antitrust policy that began with President Biden’s administration and to start broadly de-economizing antitrust litigation, both agencies should seize the opportunity to jettison the econometric-heavy market definition tests and enshrine this change within the updated merger guidelines. Enforcers should instead exclusively rely on the sensible, practical, and fair approach the Supreme Court developed in Brown Shoe.

—

Daniel A. Hanley is a Senior Legal Analyst at the Open Markets Institute. You can follow him on Mastodon @danielhanley@mastodon.social or on Twitter @danielahanley.

I love eggs. I really do. There was a year in law school where I religiously made and ate an egg sandwich for breakfast every day. To this day, I believe an egg fried in olive oil until the yolks are jammy and the edges are crispy is a perfect food.

Since last year, however, my egg-loving style has been cramped. As everyone knows, the price of eggs at the grocery store more than doubled in 2022, increasing from $1.78 a dozen in December 2021 to over $4.25 in December 2022. This 138-percent increase in egg prices far outstripped the 12-percent increase Americans saw in grocery prices generally over the same period. And some Americans have had it much worse, as average egg prices reached well over $6 a dozen in states ranging from Alabama to California and Florida to Nevada.

What’s behind the skyrocketing retail price of the incredible edible egg? Well, for one thing, the skyrocketing wholesale price of that egg. Between January 2022 and December 2022, wholesale egg prices went from 144 cents for a dozen Grade-A large eggs to 503 cents a dozen. This was the highest price ever recorded for wholesale eggs. Over the entire year, wholesale egg prices averaged 282.4 cents per dozen in 2022. When we consider that average retail egg prices for the same year were only about 3 cents higher at 285.7 cents per dozen, it becomes clear that the primary contributor to rising egg prices at the grocery store has been the dramatic increase in the wholesale prices charged by egg producers.

If this gives you hope that relief might be around the corner because you’ve heard something about a recent “collapse” in wholesale egg prices, sadly your hope would be misplaced. Despite this much-ballyhooed collapse, the average wholesale egg price has simply gone from 4-to-5 times what it was in January of last year to 2-to-3 times that number. If that weren’t enough, prices are expected to spike again when egg demand picks up in the run-up to Easter. Ultimately, the USDA is projecting that the average wholesale egg price in 2023 will be 207 cents a dozen—or only about 25% lower than the average price for 2022. So much for a collapse.

Are you wondering who sets these wholesale prices? Why, an oligopoly, of course. The production of eggs in America is dominated by a handful of companies led by Cal-Maine Foods. With nearly 47 million egg-laying hens, Cal-Maine controls approximately 20% of the national egg supply and dwarfs its nearest competitor. The leading firms in the industry have a history of engaging in “cartelistic conspiracies” to limit production, split markets, and increase prices for consumers. In fact, a jury found such a conspiracy existed as recently as 2018, and a wide-ranging lawsuit was brought just a couple of years ago accusing several of the largest egg producers (including Cal-Maine) of colluding to increase prices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When asked about the multiplying price of their product, these dominant egg producers and their industry association, the American Egg Board, have insisted it’s entirely outside their control; an avian flu outbreak and the rising cost of things like feed and fuel, they say, caused egg prices to rise all on their own in 2022. And, sure enough, those were real headaches for the egg industry last year—about 43 million egg-laying hens were lost due to bird flu through December 2022, and input costs for producers certainly increased over 2021 levels. As my organization, Farm Action, detailed in letters to federal antitrust enforcers last month, however, the math behind those explanations for the steep increase in wholesale egg prices just doesn’t add up.

The reality, we argued, is that wholesale egg prices didn’t triple in 2022, and aren’t projected to stay elevated through 2023, because of “supply chain, ‘act of God’ type stuff,” as one industry executive has tried to spin it. Rather, the true driver of record egg prices has been simple profiteering, and more fundamentally, the anti-competitive market structures that enable the largest egg producers in the country to engage in such profiteering with impunity.

Is it really just profiteering? Yes, it’s really just profiteering.

According to the industry’s leading firms, rising egg prices should be blamed on two things: avian flu and input costs. We can stipulate for the sake of argument that, if a massive amount of egg production and, hence, potential revenue were lost due to avian flu, the largest producers would be justified in trying to recoup some of that lost revenue by raising prices on their remaining sales. Likewise, if there were a sharp rise in egg production costs, we can stipulate that producers would be justified in trying to pass them on to wholesale customers. But was there a nosedive in egg production? Did the cost of egg inputs multiply dramatically? Short answer: No, and No.

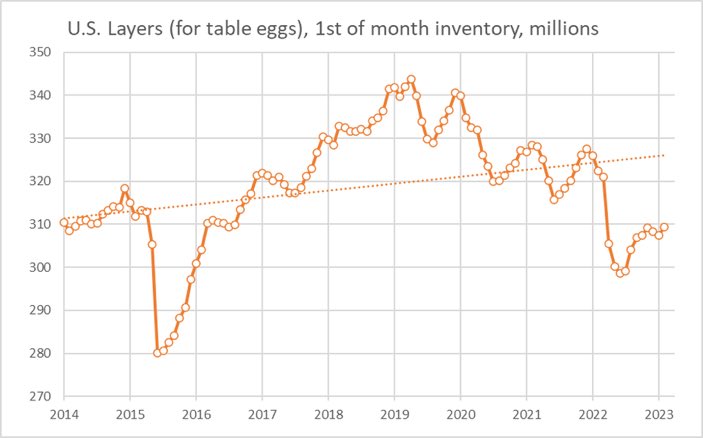

The bottom line on the avian flu outbreak is that it simply did not have a substantial effect on egg production. Although about 43 million egg-laying hens were lost due to avian flu in 2022, they weren’t all lost at once, and there were always over 300 million other hens alive and kicking to lay eggs for America. The monthly size of the nation’s flock of egg-laying hens in 2022 was, on average, only 4.8 percent smaller on a year-over-year basis. If that isn’t enough, the effect of losing those hens on production was itself blunted by “record high” lay rates throughout the year, which were, on average, 1.7 percent higher than the lay rate observed between 2017 and 2021. With substantially the same number of hens laying eggs faster than ever, the industry’s total egg production in 2022 was—wait for it—only 2.98 percent lower than it was in 2021.

Turning to input costs, it’s true they were higher in 2022 than in 2021, but they weren’t that much higher. Farm production costs at Cal-Maine Foods—the only egg producer that publishes financial data as a publicly traded company—increased by approximately 20 percent between 2021 and 2022. Their total cost of sales went up by a little over 40 percent. At the same time, Cal-Maine produced roughly the same number of eggs in 2022 as it did in 2021. If we take Cal-Maine Foods as the “bellwether” for the industry’s largest firms, we can be pretty sure that the dominant egg producers didn’t experience anywhere near enough inflation in egg production costs to account for the three-fold increase in wholesale egg prices.

Against the backdrop of these facts, the industry’s narrative simply crumbles. It’s clear that neither rising input costs nor a drop in production due to avian flu has been the primary contributor to skyrocketing egg prices. What has been the primary contributor, you ask? Profits. Lots and lots of profits.

Gross profits at Cal-Maine Foods, for example, increased in lockstep with rising egg prices through every quarter of the last year. They went from nearly $92 million in the quarter ending on February 26, 2022, to approximately $195 million in the quarter ending on May 28, 2022, to more than $217 million in the quarter ending on August 27, 2022, to just under $318 million in the quarter ending on November 26, 2022. The company’s gross margins likewise increased steadily, from a little over 19 percent in the first quarter of 2022 (a 45 percent year-over-year increase) to nearly 40 percent in the last quarter of 2022 (a 345 percent year-over-year increase).

The most telling data point, however, is this: For the 26-week period ending on November 26, 2022—in other words, for the six months following the height of the avian flu outbreak in March and April—Cal-Maine reported a five-fold increase in its gross margin and a ten-fold increase in its gross profits compared to the same period in 2021. Considering the number of eggs Cal-Maine sold during this period was roughly the same in 2022 as it was in 2021, it follows that essentially all of this profit expansion came from—you guessed it—higher prices.

But is this an antitrust problem? Yes, it’s an antitrust problem.

On their own, these numbers plainly show that dominant egg producers have been gouging Americans, using the cover of inflation and avian flu to extract profit margins as high as 40 percent on a dozen loose eggs.

Some agriculture economists and market analysts, however, have questioned whether this price gouging should raise antitrust concerns. The dramatic escalation in egg prices over the past year, they’ve argued, has just been “normal economics” at work. Per Angel Rubio, a senior analyst at the industry’s go-to market research firm, Urner Barry, the runaway increase in wholesale egg prices was simply a function of the “compounding effect” of “avian flu outbreaks month after month after month.” These outbreaks repeatedly disrupted egg deliveries, he presumes, driving customers to assent to spiraling price demands from alternative suppliers. In a blog post on Urner Barry’s website, Mr. Rubio further hypothesized that jittery customers may have “increased their ‘normal’ purchase levels to secure more supply,” goosing up prices even higher.

There are several reasons to doubt this theory of the case. To begin with, Mr. Rubio’s analysis presumes that avian flu outbreaks caused significant disruptions in the supply of eggs even though, as discussed above, the aggregate production data suggests that was not the case. But let’s assume that there were supply disruptions, and that these disruptions did lead to a glut of demand for reliable suppliers, giving them pricing power. If that were the case, it would stand to reason that Cal-Maine—which did not report a single case of avian flu at any of its facilities in 2022—had an opportunity to sell a whole lot more eggs in 2022 than in 2021, and to sell them at record-high profit margins. But Cal-Maine didn’t sell a whole lot more eggs. It sold roughly the same number of eggs. If Mr. Rubio’s theory were right, why did Cal-Maine leave money on the table?

Once we start applying this question to the pricing and production behavior of the egg industry’s dominant firms more broadly, a whole variety of competition red flags start cropping up

The red flags—they multiply!