How many times have you heard from an antitrust scholar or practitioner that merely possessing a monopoly does not run afoul of the antitrust laws? That a violation requires the use of a restraint to extend that monopoly into another market, or to preserve the original monopoly to constitute a violation? Here’s a surprise.

Both a plain reading and an in-depth analysis of the text of Section 2 of the Sherman Act demonstrate that this law’s violation does not require anticompetitive conduct, and that it does not have an efficiencies defense. Section 2 of the Sherman Act was designed to impose sanctions on any firm that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize a market. Period. With no exceptions for firms that are efficient or for firms that did not engage in anticompetitive conduct.

This is the conclusion one should reach if one were a judge analyzing the Sherman Act using textualist principles. Like most of the people reading this article I’m not a textualist. But many judges and Supreme Court Justices are, so this method of statutory interpretation must be taken quite seriously today.

To understand how to read the Sherman Act as a textualist, one must first understand the textualist method of statutory interpretation. This essay presents a textualist analysis of Section 2 that is a condensation of a 92-page law review article, titled “The Sherman Act Is a No-Fault Monopolization Statute: A Textualist Demonstration.” My analysis demonstrates that Section 2 is actually a no-fault statute. Section 2 requires courts to impose sanctions on monopolies and attempts to monopolize without inquiring into whether the defendant engaged in anticompetitive conduct or whether it was efficient.

A Brief Primer on Textualism

As most readers know, a traditionalist approach to statutory interpretation analyzes a law’s legislative history and interprets it accordingly. The floor debates in Congress and relevant Committee reports affect how courts interpret a law, especially in close cases or cases where the text is ambiguous. By contrast, textualism only interprets the words and phrases actually used in the relevant statute. Each word and phrase is given its fair, plain, ordinary, and original meaning at the time the statute was enacted.

Justice Scalia and Bryan Garner, a professor at SMU’s Dedman School of Law, wrote a 560-page book explaining and analyzing textualism. Nevertheless, a basic textualist analysis can be described relatively simply. To ascertain the meaning of the relevant words and phrases in the statute, textualism relies mostly upon definitions contained in reliable and authoritative dictionaries of the period in which the statute was enacted. These definitions are supplemented by analyzing the terms as they were used in contemporaneous legal treatises andcases. Crucially, textualism ignores statutes’ legislative history. In the words of Justice Scalia, “To say that I used legislative history is simply, to put it bluntly, a lie.”

Textualism does not attempt to discern what Congress “intended to do” other than by plainly examining the words and phrases in statutes. A textualist analysis does not add or subtract from the statute’s exact language and does not create exceptions or interpret statutes differently in special circumstances. Nor should a textualist judge insert his or her own policy preferences into the interpretation. No requirement should be read into a law unless, of course, it is explicitly contained in the legislation. No exemption should be inferred to achieve some overall policy goal Congress arguably had unless, of course, the text demands it.

As Justice Scalia wrote, “Once the meaning is plain, it is not the province of a court to scan its wisdom or its policy.” Indeed, if a court were to do so this would be the antithesis of textualism. There are some complications relevant to a textualist analysis of Section 2, but they do not change the results that follow.

A Textualist Analysis of Section 2 of the Sherman Act

A straightforward textualist interpretation of Section 2 demonstrates that a violation does not require anticompetitive conduct and applies regardless whether the firm achieved its position through efficient behavior.

Section 2 of the Sherman Act makes it unlawful for any person to “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or commerce among the several States . . . .” There is nothing, no language in Section 2, requiring anticompetitive conduct or creating an exception for efficient monopolies. A textualist interpretation of Section 2 therefore needs only to determine what the terms “monopolize” and “attempt to monopolize” meant in 1890. This examination demonstrates that these terms meant the same things they mean today if they are “fairly,” “ordinarily,” or “plainly” interpreted, free from the legal baggage that has grown up around them by a multitude of court decisions.

What Did “Monopolize” Mean in 1890?

When the Sherman Act was passed the word “monopolize” simply meant to acquire a monopoly. The term was not limited to monopolies acquired or preserved by anticompetitive conduct, and it did not exclude firms that achieved their monopoly due to efficient behavior.

As noted earlier, Justice Scalia was especially interested in the definitions of key terms in contemporary dictionaries. Scalia and Garner believe that six dictionaries published between 1851 to 1900 are “useful and authoritative.” All six were checked for definitions of “monopolize”. The principle definition in each for “monopolize” was simply that a firm had acquired a monopoly. None required anticompetitive conduct for a firm to “monopolize” a market, or excluded efficient monopolies.

For example, the 1897 edition of Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia defined “monopolize” as: “1. To obtain a monopoly of; have an exclusive right of trading in: as, to monopolize all the corn in a district . . . . ”

Serendipitously, a definition of “monopolize” was given in the Sherman Act’s legislative debates, just before the final vote on the Bill. Although normally a textualist does not care about anything uttered during a congressional debate, Senator Edmund’s remarks should be significant to a textualist because he quotes from a contemporary dictionary that Scalia considered useful and reliable. “[T]he best answer I can make to both my friends is to read from Webster’s Dictionary the definition of the verb “to monopolize”: He went on:

1. To purchase or obtain possession of the whole of, as a commodity or goods in market, with the view to appropriate or control the exclusive sale of; as, to monopolize sugar or tea.

There was no requirement of anticompetitive conduct, or exception for a monopoly efficiently gained.

These definitions are essentially the same as those in the 1898 and 1913 editions of Webster’s Dictionary. The four other dictionaries of the period Scalia & Garner considered reliable also contained essentially identical definitions. The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, from 1908, also contained a similar definition of “monopolize:”

1 . . . . To get into one’s hands the whole stock of (a particular commodity); to gain or hold exclusive possession of (a trade); . . . . To have a monopoly. . . . 2 . . . . To obtain exclusive possession or control of; to get or keep entirely to oneself.

Not only does the 1908 Oxford English Dictionary equate “monopolize” with “monopoly,” but nowhere does it require a monopolist to engage in anticompetitive conduct.

Moreover, all but one of the definitions in Scalia’s preferred dictionaries do not limit monopolies to firms making every sale in a market. They roughly correspond to the modern definition of “monopoly power,” by defining “monopolize” as the ability to control a market. The 1908 Oxford English Dictionary defined “monopolize” in part as “To obtain exclusive possession or control of.” The Webster’s Dictionary defined monopolize as “with the view to appropriate or control the exclusive sale of.” Stormonth defined monopolize as “one who has command of the market.” Latham defined monopolize as “ to have the sole power or privilege of vending.…” And Hunter & Morris defined monopolize as “to have exclusive command over.”

In summary, every one of Scalia’s preferred period dictionaries defined “monopolize” as simply to gain all the sales of a market or the control of a market. A textualist analysis of contemporary legal treatises and cases yields the same result. None required conduct we would today characterize as anticompetitive, or exclude a firm gaining a monopoly by efficient means.

A Textualist Analysis of “Attempt to Monopolize”

A textualist interpretation of Section 2 should analyze the word “attempt” as it was used in the phrase “attempt to monopolize” circa 1890. However, no unexpected or counterintuitive result comes from this examination. Circa 1890 “attempt” had its colloquial 21st Century meaning, and there was no requirement in the statute that an “attempt to monopolize” required anticompetitive conduct or excluded efficient attempts.

The “useful and authoritative” 1897 Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia defines “attempt” as:

1. To make an effort to effect or do; endeavor to perform; undertake; essay: as, to attempt a bold flight . . . . 2. To venture upon: as, to attempt the sea.— 3. To make trial of; prove; test . . . . .

The 1898 Webster’s Dictionary gives a similar definition: “Attempt . . . 1. To make trial or experiment of; to try. 2. To try to move, subdue, or overcome, as by entreaty.’ The Oxford English Dictionary, which defined “attempt” in a volume published in 1888, similarly reads: “1. A putting forth of effort to accomplish what is uncertain or difficult….”

However, the word “attempt” in a statute did have a specific meaning under the common law circa 1890. It meant “an intent to do a particular criminal thing, with an act toward it falling short of the thing intended.” One definition stated that the act needed to be “sufficient both in magnitude and in proximity to the fact intended, to be taken cognizance of by the law that does not concern itself with things trivial and small.” But no source of the period defined the magnitude or nature of the necessary acts with great specificity (indeed, a precise definition might well be impossible).

It is noteworthy that in 1881 Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote about the attempt doctrine in his celebrated treatise, The Common Law:

Eminent judges have been puzzled where to draw the line . . . the considerations being, in this case, the nearness of the danger, the greatness of the harm, and the degree of apprehension felt. When a man buys matches to fire a haystack . . . there is still a considerable chance that he will change his mind before he comes to the point. But when he has struck the match . . . there is very little chance that he will not persist to the end . . .

Congress’s choice of the phrase “attempt to monopolize” surely built upon the existing common law definitions of an “attempt” to commit robbery and other crimes. Although the meaning of a criminal “attempt” to violate a law has evolved since 1890, a textualist approach towards an “attempt to monopolize” should be a “fair” or “ordinary” interpretation of these words as they were used in 1890, ignoring the case law that has arisen since then. It is clear that acts constituting mere preparation or planning should be insufficient. Attempted monopolization should also require the intent to take over a market and at least one serious act in furtherance of this plan.

But “attempted monopolization” under Section 2 should not require the type of conduct we today consider anticompetitive, or exempt efficient conduct. Because current case law only imposes sanctions under Section 2 if a court decides the firm engaged in anticompetitive conduct,this case law was wrongly decided. It should be overturned, as should the case law that excuses efficient attempts.

Moreover, attempted monopolization’s current “dangerous probability” requirement should be modified significantly. Today it is quite unusual for a court to find that a firm illegally “attempted to monopolize” if it possessed less than 50 percent of a market.But under a textualist interpretation of Section 2, suppose a firm with only a 30 percent market share seriously tried to take over a relevant market. Isn’t a firm with a 30 percent market share often capable of seriously attempting to monopolize a market? And, of course, attempted monopolization shouldn’t have an anticompetitive conduct requirement or an efficiency exception.

Textualists Should Be Consistent, Even If That Means More Antitrust Enforcement

Where did the exception for efficient monopolies come from? How did the requirement that anticompetitive conduct is necessary for a Section 2 violation arise? They aren’t even hinted at in the text of the Sherman Act. Shouldn’t we recognize that conservative judges simply made up the anticompetitive conduct requirement and efficiency exception because they thought this was good policy? This is not textualism. It’s the opposite of textualism.

No fault monopolization embodies a love for competition and a distaste for monopoly so strong that it does not even undertake a “rule of reason” style economic analysis of the pros and cons of particular situations. It’s like a per se statute insofar as it should impose sanctions on all monopolies and attempts to monopolize. At the remedy stage, of course, conduct-oriented remedies often have been, and should continue to be, found appropriate in Section 2 cases.

The current Supreme Court is largely textualist, but also extremely conservative. Would it decide a no-fault case in the way that textualism mandates?

Ironically, when assessing the competitive effects of the Baker Hughes merger, (then) Judge Thomas changed the language of the statute from “may be substantially to lessen competition” to “will substantially lessen competition,” despite considering himself to be a textualist. So much for sticking to the language of the statute!

Until recently, textualism has only been used to analyze an antitrust law a modest number of times. This is ironic because, even though textualism has historically only been championed by conservatives, a textualist interpretation of the antitrust laws should mean that the antitrust statutes will be interpreted according to these laws’ original aggressive, populist and consumer-oriented language.

Robert Lande is the Venable Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Baltimore Law School.

Over 100 years ago, Congress responded to railroad and oil monopolies’ stranglehold on the economy by passing the United States’ first-ever antitrust laws. When those reforms weren’t enough, Congress created the Federal Trade Commission to protect consumers and small businesses from predation. Today, unchecked monopolies again threaten economic competition and our democratic institutions, so it’s no surprise that the FTC is bringing a historic antitrust suit against one of the biggest fish in the stream of commerce: Amazon.

Make no mistake: modern-day monopolies, particularly the Big Tech giants (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, and Meta), are active threats to competition and consumers’ welfare. In 2020, the House Antitrust Subcommittee concluded an extensive investigation into Big Tech’s monopolistic harms by condemning Amazon’s monopoly power, which it used to mistreat sellers, bully retail partners, and ruin rivals’ businesses through the use of sellers’ data. The Subcommittee’s report found that, as both the operator of and participant in its marketplace, Amazon functions with “an inherent conflict of interest.”

The FTC’s lawsuit builds off those findings by targeting Amazon’s notorious practice of “self-preferencing,” in which the company gathers private data on what products users are purchasing, creates its own copies of those products, then lists its versions above any competitors on user searches. Moreover, by bullying sellers looking to discount their products on other online marketplaces, Amazon has forced consumers to fork over more money than what they would have in a truly-competitive environment.

But perhaps the best evidence of Amazon’s illegal monopoly power is how hard the company has worked for years to squash any investigation into its actions. For decades, Amazon has relied on the classic ‘revolving door’ strategy of poaching former FTC officials to become its lobbyists, lawyers, and senior executives. This way, the company can use their institutional knowledge to fight the agency and criticize strong enforcement actions. These “revolvers” defend the business practices which their former FTC colleagues argue push small businesses past their breaking points. They also can help guide Amazon’s prodigious lobbying efforts, which reached a corporate record in 2022 amidst an industry wide spending spree in which “the top tech companies spent nearly $70 million on lobbying in 2022, outstripping other industries including pharmaceuticals and oil and gas.”

Amazon’s in-house legal and policy shops are absolutely stacked full of ex-FTC officials and staffers. In less than two years, Amazon absorbed more than 28 years of FTC expertise with just three corporate counsel hires: ex-FTC officials Amy Posner, Elisa Kantor Perlman and Andi Arias. The company also hired former FTC antitrust economist Joseph Breedlove as its principal economist for litigation and regulatory matters (read: the guy we’re going to call as an expert witness to say you shouldn’t break us up) in 2017.

It goes further than that. Last year, Amazon hired former Senate Judiciary Committee staffer Judd Smith as a lobbyist after he previously helped craft legislation to rein in the company and other Big Tech giants. Amazon also contributed more than $1 million to the “Competitiveness Coalition,” a Big Tech front group led by former Sen. Scott Brown (R-MA). The coalition counts a number of right-wing, anti-regulatory groups among its members, including the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a notorious purveyor of climate denialism, and National Taxpayers Union, an anti-tax group regularly gifted op-ed space in Fox News and the National Review.

This goes to show the lengths to which Amazon will go to avoid oversight from any government authority. True, the FTC has finally filed suit against Amazon, and that is a good thing. But Amazon, throughout their pursuance of ever growing monopoly power, hired their team of revolvers precisely for this moment. These ex-officials bring along institutional knowledge that will inform Amazon’s legal defense. They will likely know the types of legal arguments the FTC will rely on, how the FTC conducted its pretrial investigations, and the personalities of major players in the case.

This knowledge is invaluable to Amazon. It’s like hiring the assistant coach of an opposing team and gaining access to their playbook — you know what’s coming before it happens and you can prepare accordingly. Not only that, but this stream of revolvers makes it incredibly difficult to know the dedication of some regulators towards enforcing the law against corporate behemoths. How is the public expected to trust its federal regulators to protect them from monopoly power when a large swath of its workforce might be waiting for a monopoly to hire them? (Of course, that’s why we need both better pay for public servants as well as stricter restrictions on public servants revolving out to the corporations they were supposedly regulating.)

While spineless revolvers make a killing defending Amazon, the actual people and businesses affected by their strong arming tactics are applauding the FTC’s suit. Following the FTC’s filing, sellers praised the Agency on Amazon’s Seller Central forum, calling it “long overdue” and Amazon’s model as a “race to the bottom.” One commenter even wrote they will be applying to the FTC once Amazon’s practices force them off the platform. This is the type of revolving we may be able to support. When the FTC is staffed with people who care more about reigning in monopolies than receiving hefty paychecks from them in the future (e.g., Chair Lina Khan), we get cases that actually protect consumers and small businesses.

The FTC’s suit against Amazon signals that the federal government will no longer stand by as monopolies hollow-out the economy and corrupt the inner-workings of our democracy, but the revolvers will make every step difficult. They will be in the corporate offices and federal courtrooms advising Amazon on how best to undermine their former employer’s legal standing. They will be in the media, claiming to be objective as a former regulator, while running cover for Amazon’s shady practices that the business press will gobble up. The prevalence of these revolvers makes it difficult for current regulators to succeed while simultaneously undermining public trust in a government that should work for people, not corporations. Former civil servants who put cash from Amazon over the regulatory mission to which they had once been committed are turncoats to the public good. They should be scorned by the public and ignored by government officials and media alike.

Andrea Beaty is Research Director at the Revolving Door Project, focusing on anti-monopoly, executive branch ethics and housing policy. KJ Boyle is a research intern with the Revolving Door Project. Max Moran is a Fellow at the Revolving Door Project. The Revolving Door Project scrutinizes executive branch appointees to ensure they use their office to serve the broad public interest, rather than to entrench corporate power or seek personal advancement.

The Federal Trade Commission has accused Amazon of illegally maintaining its monopoly, extracting supra-competitive fees on merchants that use Amazon’s platform. If and when the fact-finder determines that Amazon violated the antitrust laws, we propose structural remedies to address the competitive harms. Behavioral remedies have fallen out of favor among antitrust scholars. But the success of a structural remedy cannot be taken for granted.

To briefly review the bidding, the FTC’s Complaint alleges that Amazon prevents merchants from steering customers to a lower-cost platform—that is, a platform that charges a lower take rate—by offering discounts off the price it charges on Amazon. Amazon threatens merchants’ access to the Buy Box if merchants are caught charging a lower price outside of Amazon, a variant of a most-favored-nation (MFN) restriction. In other words, Amazon won’t allow merchants to share any portions of its savings with customers as an inducement to switch platforms; doing so would put downward pressure on Amazon’s take rate, which has climbed from 35 to 45 percent since 2020 per ILSR.

The Complaint also alleges that Amazon ties its fulfillment services to access to Amazon Prime. Given the importance of Amazon Prime to survival on Amazon’s Superstore, Amazon’s policy is effectively conditioning a merchant’s access to its Superstore on an agreement to purchase Amazon’s fulfillment, often at inflated rates. Finally, the Complaint alleges that Amazon gives its own private-label brands preference in search results.

These are classic exclusionary restraints that, in another era, would be instinctively addressed via behavioral remedies. Ban the MFN, ban the tie-in, and ban the self-preferencing. But that would be wrongheaded, as doing so would entail significant oversight by enforcement authorities. As the DOJ Merger Remedies Manual states, “conduct remedies typically are difficult to craft and enforce.” To the extent that a remedy is fully conduct-based, it should be disfavored. The Remedies Manual appears to approve of conduct relief to facilitate structural relief, “Tailored conduct relief may be useful in certain circumstances to facilitate effective structural relief.”

Instead, there should be complete separation of the fulfillment services from the Superstore. In a prior piece for The Sling, we discussed two potential remedies for antitrust bottlenecks—the Condo and the Coop. In what follows, we explain that the Condo approach is a potential remedy for the Amazon platform bottleneck and the Coop approach a good remedy for the fulfillment center system. Our proposed remedy has the merit of allowing for market mechanisms to function to bypass the need for continued oversight after structural remedies are deployed.

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

Structural remedies to monopolization have, in the past, created worry about continued judicial oversight and regulation. “No one wants to be Judge Greene.” He spent the bulk of his remaining years on the bench having his docket monopolized by disputes arising from the breakup of AT&T. Breakup had also been sought in the case of Microsoft. But the D.C. Circuit, citing improper communications with the press prior to issuance of Judge Jackson’s opinion and his failure to hold a remedy hearing prior to ordering divestiture of Microsoft’s operating system from the rest of the company, remanded the case for determination of remedy to Judge Kollar-Kotelly.

By that juncture of the proceeding, a new Presidential administration brought a sea change by opposing structural remedies not only in this case but generally. Such an anti-structural policy conflicts with the pro-structural policy set forth in Standard Oil and American Tobacco—that the remedy for unlawful monopolization should be restructuring the enterprises to eliminate the monopoly itself. The manifest problem with the AT&T structural remedy and the potential problem with the proposed remedy in Microsoft is that neither removed the core monopoly power that existed, thus retaining incentives to engage in anticompetitive conduct and generating continued disputes.

The virtue of the structural approaches we propose is that once established, they should require minimal judicial oversight. The ownership structures would create incentives to develop and operate the bottlenecks in ways that do not create preferences or other anticompetitive conduct. With an additional bar to re-acquisition of critical assets, such remedies are sustainable and would maximize the value of the bottlenecks to all stakeholders.

Turn Amazon’s Superstore into a Condo

The condominium model is one in which the users would “own” their specific units as well as collectively “owning” the entire facility. But a distinct entity would provide the administration of the core facility. Examples of such structures include the current rights to capacity on natural gas pipelines, rights to space on container ships, and administration for standard essential patents and for pooled copyrights. These examples all involve situations in which participants have a right to use some capacity or right but the administration of the system rests with a distinct party whose incentive is to maximize the value of the facility to all users. In a full condominium analogy, the owners of the units would have the right to terminate the manager and replace it. Thus, as long as there are several potential managers, the market would set the price for the managerial service.

A condominium mode requires the easy separability of management of the bottleneck from the uses being made of it. The manager would coordinate the uses and maintain the overall facility while the owners of access rights can use the facility as needed.

Another feature of this model is that when the rights of use/access are constrained, they can be tradable; much as a condo owner may elect to rent the condo to someone who values it more. Scarcity in a bottleneck creates the potential for discriminatory exploitation whenever a single monopolist holds those rights. Distributing access rights to many owners removes the incentive for discriminatory or exclusionary conduct, and the owner has only the opportunity to earn rents (high prices) from the sale or lease of its capacity entitlement. Thus, dispersion of interests results in a clear change in the incentives of a rights holder. This in turn means that the kinds of disputes seen in AT&T’s breakup are largely or entirely eliminated.

The FTC suggests skullduggery in the operation of the Amazon Superstore. Namely, degrading suggestions via self-preferencing:

Amazon further degrades the quality of its search results by buying organic content under recommendation widgets, such as the “expert recommendation” widget, which display Amazon’s private label products over other products sold on Amazon.

Moreover, in a highly redacted area of the complaint, the FTC alleges that Amazon has the ability to “profitably worsen its services.”

The FTC also alleges that Amazon bars customers from “multihoming:”

[Multihoming is] simultaneously offering their goods across multiple online sales channels. Multihoming can be an especially critical mechanism of competition in online markets, enabling rivals to overcome the barriers to entry and expansion that scale economies and network effects can create. Multihoming is one way that sellers can reduce their dependence on a single sales channel.

If the Superstore were a condo, the vendors would be free to decide how much to focus on this platform in comparison to other platforms. Merchants would also be freed from the MFN, as the condo owner would not attempt to ban merchants from steering customers to a lower-cost platform.

Condominiumization of the Amazon Superstore would go a long way to reducing what Cory Doctorow might call the “enshittification” of the Amazon Superstore. Given its dominance over merchants, it would probably be necessary to divest and rebrand the “Amazon basics” business. Each participating vendor (retailer or direct selling manufacturer) would share in the ownership of the platform and would have its own place to promote its line of goods or services.

The most challenging issue is how to handle product placement on the overall platform. Given the administrator’s role as the agent of the owners, the administrator should seek to offer a range of options. Or leave it to owners themselves to create joint ventures to promote products. Alternatively, specific premium placement could go to those vendors that value the placement the most, rather than based on who owns the platform. The revenue would in turn be shared among the owners of the condo. Thus, the platform administrator would have as its goal maximizing the value of the platform to all stakeholders. This would also potentially resolve some of the advertising issues. According to the Complaint,

Amazon charges sellers for advertising services. While Amazon also charges sellers other fees, these four types constitute over [redacted] % of the revenue Amazon takes in from sellers. As a practical matter, most sellers must pay these four fees to make a significant volume of sales on Amazon.

Condo ownership would mean that the platform constituents would be able to choose which services they purchase from the platform, thereby escaping the harms of Amazon’s tie-in. Constituents could more efficiently deploy advertising resources because they would not be locked-into or compelled to buy from the platform.

Optimization would include information necessary for customer decision-making. One of the other charges in the Complaint was the deliberate concealment of meaningful product reviews:

Rather than competing to secure recommendations based on quality, Amazon intentionally warped its own algorithms to hide helpful, objective, expert reviews from its shoppers. One Amazon executive reportedly said that “[f]or a lot of people on the team, it was not an Amazonian thing to do,” explaining that “[j]ust putting our badges on those products when we didn’t necessarily earn them seemed a little bit against the customer, as well as anti-competitive.”

Making the platform go condo does not necessarily mean that all goods are treated equally by customers. That is the nature of competition. It would mean that in terms of customer information, however, a condominiumized platform would enable sellers to have equal and nondiscriminatory access to the platform and to be able to promote themselves based upon their non-compelled expenditures.

Turn Amazon’s Fulfillment Center in a Coop

The Coop model envisions shared user ownership, management, and operation of the bottleneck. Such transformation of ownership should change the incentives governing the operation and potential expansion of the bottleneck.

The individual owner-user stands to gain little by trying to impose a monopoly price on users including itself or by restricting access to the bottleneck by new entrants. So long as there are many owners, the primary objective should be to manage the entity so that it operates efficiently and with as much capacity as possible.

This approach is for enterprises that require substantial continued engagement of the participants in the governance of the enterprise. With such shared governance, the enterprise will be developed and operated with the objective of serving the interest of all participants.

The more the bottleneck interacts directly with other aspects of the users’ or suppliers’ activity, the more those parties will benefit from active involvement in the decisions about the nature and scope of the activity. Historically, cooperative grain elevators and creameries provided responses to bottlenecks in agriculture. Contemporary examples could include a computer operating system, an electric transmission system, or social media platform. In each, there are a myriad of choices to be made about design or location or both. Different stakeholders will have different needs and desires. Hence, the challenge is to find a workable balance of interests. That maximizes the overall value of the system for its participants rather than serving only the interests of a single owner.

This method requires that no party or group dominates the decision processes, and all parties recognize their mutual need to make the bottleneck as effective as possible for all users. Enhancing use is a shared goal, and the competing experiences and needs should be negotiated without unilateral action that could devalue the collective enterprise.

As explained above, Amazon tie-in effectively requires that all vendors using its platform must also use Amazon’s fulfillment services. Yet distribution is distinct from online selling. Hence, the distribution system should be structurally separated from the online superstore. Indeed, vendors using the platform condo may not wish to participate in the distribution system regardless of access. Conversely, vendors not using the condo platform might value the fulfillments services for orders received on their platforms. Still other vendors might find multi-homing to be the best option for sales. As the Complaint points out, multi-homing may give rise to other benefits if not locked into Amazon Distribution:

Sellers could multihome more cheaply and easily by using an independent fulfillment provider- a provider not tied to any one marketplace to fulfill orders across multiple marketplaces. Permitting independent fulfillment providers to compete for any order on or off Amazon would enable them to gain scale and lower their costs to sellers. That, in turn, would make independent providers even more attractive to sellers seeking a single, universal provider. All of this would make it easier for sellers to offer items across a variety of outlets, fostering competition and reducing sellers’ dependence on Amazon.

The FTC Complaint alleges that Amazon has monopoly power in its fulfillment services. This is a nationwide complex of specialized warehouses and delivery services. The FTC is apparently asserting that this system has such economies of scale and scope that it occupies a monopoly bottleneck for the distribution of many kinds of consumer goods. If a single firm controlled this monopoly, it would have incentives to engage in exploitative and exclusionary conduct. Our proposed remedy to this is a cooperative model. Then, the goal of the owners is to minimize the costs of providing the necessary service. These users would need to be more directly involved in the operation of the distribution system as a whole to ensure its development and operation as an efficient distribution network.

Indeed, its users might not be exclusively users of the condominiumized platform. Like other cooperatives, the proposal is that those who want to use the service would join and then participate in the management of the service. Separating distribution from the selling platform would also enhance competition between sellers who opt to use the cooperative distribution and those that do not. For those that join the distribution cooperative, the ability to engage in the tailoring of those distribution services without the anticompetitive constraints created by its former owner (Amazon) would likely result in reduced delivery costs.

Separation of Fulfillment from Superstore Is Essential for Both Models

We propose some remedies to the problems articulated in the FTC’s Amazon Complaint—at least the redacted version. Thus, we end with some caveats.

First, we do not have access to the unredacted Complaint. Thus, to the extent that additional information might make either of our remedies improbable, we certainly do not have access to that information as of now.

Second, these condo and cooperative proposals go hand in hand with other structural remedies. There should be separation of the Fulfillment services from the Superstore and Amazon Brands might have to be divested or restructured. Moreover, their recombination should be permanently prohibited. These are necessary conditions for both remedies to function properly.

Third, in both the condo and coop model, governance structures must be in place to assure that both fulfillment services and the Superstore are not recaptured by a dominant player. In most instances, a proper governance structure would bar that. The government should not hesitate to step in should capture be evident.

Peter C. Carstensen is a Professor of Law Emeritus at the Law School of University of Wisconsin-Madison. Darren Bush is Professor of Law at University of Houston Law Center.

“Their goal is simply to mislead, bewilder, confound, and delay and delay and delay until once again we lose our way, and fail to throw off the leash the monopolists have fastened on our neck.” – Barry Lynn

Today, the name Draper is associated with either a fictional adman or a successful real-life venture capital dynasty.

Among the latter, the late Bill Draper was a widely respected early investor in Skype, OpenTable, and other top-tier startups. Less remembered now is the role of the family patriarch—Bill’s father, General William Henry Draper, Junior—in shaping the course of history in postwar Germany and Japan. Well before founding Silicon Valley’s first venture capital firm in 1959, the ür-Draper had made a name for himself in other powerful circles. A graduate of New York University with both a bachelor’s and a master’s in economics, Draper’s early career alternated between stints in investment banking and military service. During World War II, his experience spanned the gamut from developing military procurement policies to commanding an infantry. Socially savvy and obsessively hard-working, Draper was tapped to lead the “economic side of the occupation,” known as the Economics Division, well before Germany officially surrendered in May 1945.

The structure of the military government was cobbled together that summer and fall. Meanwhile, Washington hammered out the principles of occupation policy. Because Germany had surrendered unconditionally, the Allies had “supreme authority” to govern and reform their respective zones. Despite sharp rifts between U.S. agencies about whether Germany deserved a “soft” or a “hard” peace, some goals remained consistent after FDR’s death in April 1945. Notably, there was consensus that Germany’s political and economic systems would both have to be reformed to prevent war and promote democracy.

President Truman personally embraced such principles, which were spelled out in an order from the Joint Chiefs of Staff dictating the mission of the military governor, as well as in the August 1945 Potsdam Agreement between the Allies. The latter document instructed that “[a]t the earliest practicable date, the German economy shall be decentralized for the purpose of eliminating the present excessive concentration of economic power as exemplified in particular by cartels, syndicates, trusts and other monopolistic arrangements.” This policy was undergirded by years of Congressional hearings on how German industry had assisted Hitler’s consolidation of power and path to war.

So how did Draper approach building his Economics Division in light of these mandates? He entrusted an executive from (then monopoly) AT&T to hire men from their network of New York bankers and big business executives. An ominous start, running counter to the antimonopoly mission. There does not appear to have been any effort to recruit staff with more diverse business experience. Draper himself was still technically on leave from Dillon, Read, & Company—an investment bank that, in the decades after World War I, had underwritten over $100 million in German industrial bonds. Those bonds had enabled a German steel firm to buy out its competitors to become the largest steel combine in Germany—and then, the ringmaster of an international cartel.

When the military government’s organizational chart was finalized in the fall of 1945, the Economics Division had swallowed up several other sister proto-divisions, including the group that was investigating cartels and monopolies. This essentially inverted the structure of U.S. domestic enforcement: it was as if economists ran the Federal Trade Commission. Draper later denied engineering this chain of command, which indeed may have been prompted by other factors, including the inconvenient tendency of early decentralization leaders to make press leaks about the military government’s failure to remove some prominent Nazis from positions of power. And at first, Draper was not focused on what the group was doing—he initially viewed their work as tackling “just one of a great many problems.”

Archival footage of the early days

After Senate scrutiny jump-started recruitment of trustbusters en masse, the consequences of depriving the group of Division status became more apparent. The longest-serving leader of the “Decartelization Branch,” James Stewart Martin, had spent much of the war in an “economic warfare” unit investigating warmongering German firms. His team quickly dove into expanding this research and developing legal cases that would be ready to launch once the military government enacted the equivalent of an antitrust law.

Draper believed in bright line rules when it came to cartel agreements: they “should be eliminated, made illegal and prohibited.” Military government eventually passed a law which announced that participation in any international cartel “is hereby declared illegal and is prohibited,” and a year later issued regulations requiring firms to send “notices of termination” informing counterparties that cartel terms were illegal. But Draper viewed “deconcentration” (breaking up combines) differently. He later proclaimed agreement with the general policy, but carefully qualified his statements with loose caveats about not “breaking down the economic situation.” According to members of the Decartelization Branch, Draper and his men thought deconcentration would threaten Germany’s ability to ramp up production enough to sustain itself through exports—even though staffers repeatedly explained that deconcentration would increase output. (The Division’s incessant questioning of the premises of the official U.S. policy may not have been driven by corruption, but also does not appear to have been grounded in evidence, just ideological instincts borne from their professional circles.)

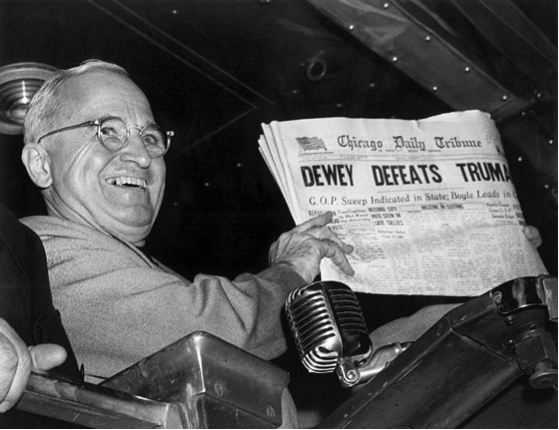

Draper and his men increasingly wielded their veto power to thwart deconcentration efforts. According to Martin, Draper personally teamed up with an intransigent counterpart on the British side to undermine the official U.S. position, successfully delaying negotiation of the law for a year and a half and ultimately weakening the final product. Draper allegedly insisted that accused German firms should be given procedural rights that exceeded those given to domestic companies under U.S. antitrust law—an extraordinary position to take in the context of a hyper-concentrated economy lead by firms that had proactively plotted how they would commandeer rivals in conquered nations. (The timeline allotted for objections and appeals would, coincidentally, postpone final adjudication until after the next U.S. Presidential election, when members of the Economics Division might expect headlines to read “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN.”).

How that gamble turned out (hint: man on left is not Dewey)

There are rarely controls in public policy, but it is telling that the successes in decentralizing Germany’s economy occurred in areas beyond Draper’s veto power—that is, outside of the Decartelization Branch. One signature accomplishment of military government was breaking up the notorious chemical combine I.G. Farben. The United States had captured Farben’s seven-story headquarters in April 1945, and the deputy military governor personally focused on ensuring that a law authorizing the seizure and dissolution of Farben was enacted by all of the Allies by the end of that year. Draper seems to have essentially regarded Farben as the spoils of war, acknowledging that policy considerations other than any potential impact on production or German recovery took precedence in that decision. In any event, the officers in charge of overseeing Farben’s break up reported directly to the military governor, not to Draper. Although Farben was not dispersed to the extent originally envisioned, the military government followed through on reversing the merger that had cemented Farben’s monopoly by spinning off three large successors and a dozen smaller businesses. Another telling accomplishment was the reorganization of the banks into a Federal Reserve-like system. That was handled by the Finance Division, which had co-equal status with Draper’s Economics Division.

Farben and the banks were undoubtedly among the most important targets for decentralizing Germany’s economy, but were likely not the only worthy targets. Wartime investigations concluded that fewer than 100 men controlled over two-thirds of Germany’s industrial system by sitting on the boards of Germany’s Big Six Banks along with 70 industrial combines and holding companies. Although some major industries, such as steel and coal, were located in the British zone, over two dozen firms were based in the U.S. zone. The failure of the military government to launch any actions against any other combines after two years of occupation suggests that something other than good faith disagreements about particular procedures or particular companies was afoot.

There is much, much more to this story: a “factfinding” mission by U.S. industrialists, a cameo by ex-President Herbert Hoover, an untimely marriage, lies, press leaks, Congressional hearings, an internal Army investigation, righteous resignations, early retirements, and more. Not to mention that time Draper swooped into postwar Japan to copy-paste his preferred economic prescriptions over General MacArthur’s reform program there.

Of course, it would be a stretch to conclude that the Decartelization Branch failed to implement a robust antimonopoly program because of one man alone. Others have suggested that even an unhobbled program would have been doomed sooner or later by bickering Allies, changing control of Congress, and the beginning of the Cold War two years into the occupation. Or, perhaps, by the inherent irony of a centralized military tasked with decentralizing a society.

Yet these explanations divert attention from the key ingredients of the pivotal “first 100 days” of any endeavor: institutional structure and selection of mission-aligned leadership. Different choices at that crucial stage might have yielded some tangible early successes and built momentum that could have weathered later headwinds. Taking this possibility seriously underscores why, in modern times, President Biden’s establishment of the competition council and appointment of “Wu, Khan, and Kanter” were so essential—and why ongoing missed opportunities in the administration are so troubling. Elevating amoral excellence and reputed raw managerial ability over other leadership qualifications has consequences. The story of the Decartelization Branch also provides deeper context for understanding how trustbusters approached their work upon returning to the Department of Justice, and for the political will that drove adoption of the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950.

The saga of the Decartelization Branch will be explored in detail in a forthcoming Substack series. This is, for the most part, not a new story, but it is apparently not well-known in antitrust circles; some of the most extensive accounts were written by historians who came across the saga in the course of researching bigger questions, such as the genesis of the Cold War and the rise and fall of international cartels. Perhaps most importantly, the series will be accompanied by new scans of primary sources, to facilitate renewed scholarship into this era.

Laurel Kilgour is a startup attorney in private practice, and also teaches policy courses. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the author’s employers or clients. This is not legal advice about any particular legal situation. To the extent any states might consider this attorney advertising, those states sure have some weird and counterintuitive definitions of attorney advertising.

As the DOJ’s antitrust case against Google begins, all eyes are focused on whether Google violated antitrust law by, among other things, entering into exclusionary agreements with equipment makers like Apple and Samsung or web browsers like Mozilla. Per the District Court’s Memorandum Opinion, released August 4, “These agreements make Google the default search engine on a range of products in exchange for a share of the advertising revenue generated by searches run on Google.” The DOJ alleges that Google unlawfully monopolizes the search advertising market.

Aside from matters relating to antitrust liability, an equally important question is what remedy, if any, would work to restore competition in search advertising in particular and online advertising generally?

Developments in the UK might shed some light. The UK Treasury commissioned a report to make recommendations on changes to competition law and policy, which aimed to “help unlock the opportunities of the digital economy.” The report found that Big Tech’s monopolizing of data and control over open web interoperability could undermine innovation and economic growth. Big Tech platforms now have all the data in their hands, block interoperability with other sources, and will capture more of it, through their huge customer-facing machines, and so can be expected to dominate the data needed for the AI Period, enabling them to hold back competition and economic growth.

The dominant digital platforms currently provide services to billions of end users. Each of us has either an Apple or Android device in our pocket. These devices operate as part of integrated distribution platforms: anything anyone wants to obtain from the web goes through the device, its browser (often Google’s search engine), and the platform before accessing the Open Web, if not staying on an app on an apps store within the walls of the garden.

Every interaction with every platform product generates data, refreshed billions of times a day from multiple touch points providing insight into buying intent and able to predict people’s behavior and trends.

All this data is used to generate alphanumeric codes that match data contained in databases (aka “Match Keys”), which are used to help computers interoperate and serve relevant ads to match users’ interests. These were for many years used by all from the widely distributed Double Click ID. They were shared across the web and were used as the main source of data by competing publishers and advertisers. After Google bought Double Click and grew big enough to “tip” the market, however, Google withdrew access to its Match Keys for its own benefit.

The interoperability that is a feature of the underlying internet architecture has gradually been eroded. Facebook collected its own data from user’s “Likes” and community groups and also withdrew access for independent publishers to its Match Key data, and recently Apple has restricted access to Match Key data that is useful for ads for all publishers, except Google has a special deal on search and search data. As revealed in U.S. vs Google, Apple is paid over $10 billion a year by Google so that Google can provide its search product to Apple users and gather all their search history data that it can then use for advertising. The data generated by end user interactions with websites is now captured and kept within each Big Tech walled garden.

If the Match Keys were shared with rival publishers for use in their independent supply channel and used by them for their own ad-funded businesses, interoperability would be improved and effective competition could be generated with the tech platforms. Competition probably won’t exist otherwise.

Both Google and Apple currently impose restrictions on access to data and interoperability. Cookie files also contain Match Keys that help maintain computer sessions and “state” so that different computers can talk to each other and help remember previous visits to websites and enable e-commerce. Cookies do not themselves contain personal data and are much less valuable than the Match Keys that were developed by Double Click or ID for advertisers, but they do provide something of a substitute source of data about users’ intent to purchase for independent publishers.

Google and Apple are in the process of blocking access to Match Keys in all forms to prevent competitors from obtaining relevant data about users needs and wants. They also prevent the use of the Open Web and limit the inter-operation of their apps stores with Open Web products, such as progressive web apps.

The UK’s Treasury Report refers to interoperability 8 times and the need for open standards as a remedy 43 times; the Bill refers to interoperability and we are expecting further debate about the issue as the Bill passes through Parliament.

A Brief History of Computing and Communications

The solution to monopolization, or lack of competition, is the generation of competition and more open markets. For that to happen in digital worlds, access to data and interoperability is needed. Each previous period of monopolization involved intervention to open-up computer and communications interfaces via antitrust cases and policy that opened market and liberalized trade. We have learned that the authorities need to police standards for interoperability and open interfaces to ensure the playing field is level and innovation can take place unimpeded.

IBM’s activity involved bundling computers and peripherals and the case was eventually solved by unbundling and unblocking interfaces needed by competitors to interoperate with other systems. Microsoft did the same, blocking third parties from interoperating via blocking access to interfaces with its operating system. Again, it was resolved by opening-up interfaces to promote interoperability and competition between products that could then be available over platforms.

When Tim Berners Lee created the World Wide Web in the early 1990s, it took place nearly ten years after the U.S. courts imposed a break-up of AT&T and after the liberalization of telecommunications data transmission markets in the United States and the European Union. That liberalization was enabled by open interfaces and published standards. To ensure that new entrants could provide services to business customers, a type of data portability was mandated, enabling numbers held in incumbent telecoms’ databases to be transferred for use by new telecoms suppliers. The combination of interconnection and data portability neutralized the barrier to entry created by the network effect arising from the monopoly control over number data.

The opening of telecoms and data markets in the early 1990s ushered in an explosion of innovation. To this day, if computers operate to the Hyper Text Transfer Protocol then they can talk to other computers. In the early 1990s, a level playing field was created for decentralized competition among millions of businesses.

These major waves of digital innovation perhaps all have a common cause. Because computing and communications both have high fixed costs and low variable or incremental costs, and messaging and other systems benefit from network effects, markets may “tip” to a single provider. Competition in computing and communications then depends on interoperability remedies. Open, publicly available interfaces in published standards allow computers and communications systems to interoperate; and open decentralized market structures mean that data can’t easily be monopolized.

It’s All About the Match Keys

The dominant digital platforms currently capture data and prevent interoperability for commercial gain. The market is concentrated with each platform building their own walled gardens and restricting data sharing and communication across. Try cross-posting among different platforms as an example of a current interoperability restriction. Think about why messaging is restricted within each messaging app, rather than being possible across different systems as happens with email. Each platform restricts interoperability preventing third-party businesses from offering their products to users captured in their walled gardens.

For competition to operate in online advertising markets, a similar remedy to data portability in the telecom space is needed. Only, with respect to advertising, the data that needs to be accessed is Match Key data, not telephone numbers.

The history of anticompetitive abuse and remedies is a checkered one. Microsoft was prohibited from discriminating against rivals and had to put up a choice screen in the EU Microsoft case. It didn’t work out well. Google was similarly prohibited by the EU in Google search (Shopping) from (1) discriminating against rivals in its search engine results pages, (2) entering exclusive agreements with handset suppliers that discriminated against rivals, and (3) showing only Google products straight out of the box in the EU Android case. The remedies did not look at the monopolization of data and its use in advertising. Little has changed and competitors claim that the remedies are ineffective.

Many in the advertising publishing and ad tech markets recall that the market worked pretty well before Google acquired Double Click. Google uses multiple data sources as the basis for its Match Keys and an access and interoperability remedy might be more effective, proportionate and less disruptive.

Perhaps if the DOJ’s case examines why Google collects search data from its search engine, its use of search histories, browser histories and data from all interactions with all products for its Match Key for advertising, the court will better appreciate the importance of data for competitors and how to remedy that position for advertising-funded online publishing.

Following Europe’s Lead

The EU position is developing. Under the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), which now supplements EU antitrust law as applied in the Google Search and Android Decisions, it is recognized that people want to be able to provide products and services across different platforms or cross-post or communicate with people connected to each social network or messaging app. In response, the EU has imposed obligations on Big Tech platforms in Articles 5(4) and 6(7) that provide for interoperability and require gatekeepers to allow open access to the web.

Similarly, Section 20.3 (e) of the UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC) refers to interoperability and may be the subject of forthcoming debate as the bill passes further through Parliament. Unlike U.S. jurisprudence with its recent fixation on consumer welfare, the objective of the Competition and Markets Authority is imposed by the law. The obligation to “promote competition for the benefit of consumers” is contained in EA 2013 s 25(3). This can be expressly related to intervention opening up access to the source of the current data monopolies: the Match Keys could be shared, meaning all publishers could get access to IDs for advertising (i.e., operating systems generated IDs such as Apple’s IDFA or Google’s Google ID or MAID).

In all jurisdictions it will be important for remedies to stimulate innovation, and to ensure that competition is promoted between all products that can be sold online, rather than between integrated distribution systems. Moreover, data portability needs to apply with reference to use of open and interoperable Match Keys that can be used for advertising, and that way address the data monopolization risk. As with the DMA, the DMCC should contain an obligation for gatekeepers to ensure fair reasonable and nondiscriminatory access, and treat advertisers in a similar way to that through which interoperability and data potability addressed monopoly benefits in previous computer, telecoms, and messaging cases.

Tim Cowen is the Chair of the Antitrust Practice at the London-based law firm of Preiskel & Co LLP.

This piece originally appeared in ProMarket but was subsequently retracted, with the following blurb (agreed-upon language between ProMarket’s Luigi Zingales and the authors):

“ProMarket published the article “The Antitrust Output Goal Cannot Measure Welfare.” The main claim of the article was that “a shift out in a production possibility frontier does not necessarily increase welfare, as assessed by a social welfare function.” The published version was unclear on whether the theorem contained in the article was a statement about an equilibrium outcome or a mere existence claim, regardless of the possibility that this outcome might occur in equilibrium. When we asked the authors to clarify, they stated that their claim regarded only the existence of such points, not their occurrence in equilibrium. After this clarification, ProMarket decided that the article was uninteresting and withdrew its publication.”

The source of the complaint that caused the retraction was, according to Zingales, a ProMarket Advisory Board member. The authors had no contact with that person, nor do we know who it is. We would have welcomed published scholarly debate versus retraction compelled by an anonymous Board Member.

We reproduce the piece in its entirety here. In addition, we provide our proposed revision to the piece, which we wrote to clear up the confusion that it was claimed was created by the first piece. We will let our readers be the judge of the piece’s interest. Of course, if you have any criticisms, we welcome professional scholarly debate.

(By the way, given that the piece never mentions supply or demand or prices, it is a mystery to us why any competent economist could have thought it was about “equilibrium.” But perhaps “equilibrium” was a pretext for removing the article for other reasons.)

The Antitrust Output Goal Cannot Measure Welfare (ORIGINAL POST)

Many antitrust scholars and practitioners use output to measure welfare. Darren Bush, Gabriel A. Lozada, and Mark Glick write that this association fails on theoretical grounds and that ideas of welfare require a much more sophisticated understanding.

By Darren Bush, Gabriel A. Lozada, and Mark Glick

Debate seems to have pivoted in the discourse on consumer welfare theory to the question of whether welfare can be indirectly measured based upon output. The tamest of these claims is not that output measures welfare, but that generally, output increases are associated with increases in economic welfare.

This claim, even at its tamest, is false. For one, welfare depends on more than just output, and increasing output may detrimentally affect some of the other factors which welfare depends on. For example, increasing output may cause working conditions to deteriorate; may cause competing firms to close, resulting in increased unemployment, regional deindustrialization, and fewer avenues for small business formation; may increase pollution; may increase the political power of the growing firm, resulting in more public policy controversies and, yes, more lawsuits being decided in its interest; and may adversely affect suppliers.

Even if we completely ignore those realities, it is still possible for an increase in output to reduce welfare. These two short proofs show that even in the complete absence of these other effects—that is, even if we assume that people obtain welfare exclusively by receiving commodities, which they always want more of—increasing output may reduce welfare.

We will first prove that it is possible for an increase in output to reduce welfare under the assumption that welfare is assessed by a social planner. Then we will prove it assuming no social planner, so that welfare is assessed strictly via individuals’ utility levels.

The Social Planner Proof

Here we show that a shift out in a production possibility frontier does not necessarily increase welfare, as assessed by a social welfare function.

Suppose in the figure below that the original production possibility frontier is PPF0 and

the new production possibility frontier is PPF1. Let USWF be the original level of social welfare, so that the curve in the diagram labeled USWF is the social indifference curve when the technology is represented by PPF0. This implies that when the technology is at PPF0, society chooses the socially optimal point, I, on PPF0. Next, suppose there is an increase in potential output, to PPF1. If society moves to a point on PPF1 which is above and to the left of point A, or is below and to the right of point B, then society will be worse off on PPF1 than it was on PPF0. Even though output increased, depending on the social indifference curve and the composition of the new output, there can be lower social welfare.

The Individual Utility Proof

Next, we continue to assume that only consumption of commodities determines welfare, and we show that when output increases every individual can be worse off. Consider the figure below, which represents an initial Edgeworth Box having solid borders, and a new, expanded Edgeworth Box, with dashed borders. The expanded Edgeworth Box represents an increase in output for both apples and bananas, the two goods in this economy.

The original, smaller Edgeworth Box has an origin for Jones labeled J and an origin for Smith labeled S. In this smaller Edgeworth Box, suppose the initial position is at C. The indifference curve UJ0 represents Jones’s initial level of utility with the smaller Edgeworth Box, and the indifference curve US represents Smith’s initial level of utility with the smaller Box. In the larger Edgeworth Box, Jones’s origin shifts from J to J’, and his UJ0 indifference curve correspondingly shifts to UJ0′. Smiths’ US indifference curve does not shift. The hatched areas in the graph are all the allocations in the bigger Edgeworth Box which are worse for both Smith and Jones compared to the original allocation in the smaller Edgeworth Box.

In other words, despite the fact that output has increased, if the new allocation is in the hatched area, then Smith and Jones both prefer the world where output is lower. We get this result because welfare is affected by allocation and distribution as well as by the sheer amount of output, and more output, if mis-allocated or poorly distributed, can decrease welfare.

GDP also does not measure aggregate Welfare

The argument that “output” alone measures welfare sometimes refers not to literal output, as in the two examples above, but to a reified notion of “output.” A good example is GDP. GDP is the aggregated monetary value of all final goods and services, weighted using current prices. Welfare economists, beginning with Richard Easterlin, have understood that GDP does not accurately measure economic well-being. Since prices are used for the aggregation, GDP incorporates the effects of income distribution, but in a way which hides this dependence, making GDP seem value-free although it is not. In addition, using GDP as a measure of welfare deliberately ignores many important welfare effects while only taking into account output. As Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy put it:

GDP takes a positive count of the cars we produce but does not account for the emissions they generate; it adds the value of the sugar-laced beverages we sell but fails to subtract the health problems they cause; it includes the value of building new cities but does not discount for the vital forests they replace. As Robert Kennedy put it in his famous election speech in 1968, “it [GDP] measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

Any industry-specific measure of price-weighted “output” or firm-specific measure of price-weighted “output” is similarly flawed.

For these reasons, few, if any, welfare economists would today use GNP alone to assess a nation’s welfare, preferring instead to use a collection of “social indicators.”

Conclusion

Output should not be the sole criterion for antitrust policy. We can do a better job of using competition policy to increase human welfare without this dogma. In this article, we showed that we cannot be certain that output increases welfare even in a purely hypothetical world where welfare depends solely on the output of commodities. In the real world, where welfare depends on a multitude of factors besides output—many of which can be addressed by competition policy—the case against a unilateral output goal is much stronger.

Addendum

The Original Sling posting inadvertently left off the two proposed graphs that we drew as we sought to remedy the Anonymous Board Member’s confusion about “equilibrium.” We now add the graphs we proposed. The explanation of the graphs was similar, and the discussion of GNP was identical to the original version.

The Proof if there is a Social Welfare Function (Revised Graph)

The Individual Utility Proof (Revised Graph)

Over the past two years, heterodox economic theory has burst into the public eye more than ever as conventional macroeconomic models have failed to explain the economy we’ve been living in since 2020. In particular, theories around consolidation and corporate power as factors in macroeconomic trends–from neo-Brandeisian antitrust policy to theories of profit seeking as a driver of inflation–have exploded onto the scene. While “heterodox economics” isn’t really a singular thing–it’s more a banner term for anything that breaks from the well established schools of thought–the ideas it represents challenge decades of consensus within macro- and financial economics. This development, of course, has left the proponents of the traditional models rather perturbed.

One of the heterodox ideas that has seen the most media attention is the idea of sellers’ inflation: the theory that inflation can, at least partially, be a result of companies using economic shocks as smokescreens to exercise their market power and raise the prices they charge. The name most associated with this theory is Isabella Weber, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, but there are certainly other economists who support this theory (and many more who support elements of it but are holding out for more empirical evidence before jumping into the rather fraught public debate.)

Conventional economists have been bristling about sellers’ inflation being presented as an alternative to the more staid explanation of a wage-price spiral (we’ll come back to that), but in recent months there have been extremely aggressive (and often condescending, self-important, and factually incorrect) attacks on the idea and its proponents. Despite this, sellers’ inflation really is not that far from a lot of long standing economic theory, and the idea is grounded in key assumptions about firm behavior that are deeply held across most economic models.

My goal here is threefold: first, to explain what the sellers’ inflation and conventional models actually are; second, to break down the most common lines of attack against sellers’ inflation; third, to demonstrate that, whatever its shortcomings, sellers’ inflation is better supported than the traditional wage-price spiral. Many even seem to recognize this, shifting to an explanation of corporations just reacting to increased demand. As we’ll see, that explanation is even weaker.

What Is Sellers’ Inflation?

The Basic Story

As briefly mentioned above, sellers’ inflation is the idea that, in significantly concentrated sectors of the economy, coordinated price hikes can be a significant driver of inflation. While the concept’s opponents generally prefer to call it “greedflation,” largely as a way of making it seem less intellectually serious, the experts actually advancing the theory never use that term for a very simple reason: it doesn’t really have anything to do with variance in how greedy corporations are. It does rely on corporations being “greedy,” but so do all mainstream economic theories of corporate behavior. Economic models around firm behavior practically always assume companies to be profit maximizing, conduct which can easily be described as greedy. As we’ll see, this is just one of many points in which sellers’ inflation is actually very much aligned with prevailing economic theory.

Under the sellers’ inflation model, inflation begins with a series of shocks to the macroeconomy: a global pandemic causes an economic crash. Governments respond with massive fiscal stimulus, but the economy experiences huge supply chain disruptions that are further worsened with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. All of these events caused inflation to increase either by decreasing supply or increasing demand. The stimulus checks increased demand by boosting consumers’ spending power–exactly what it was supposed to do. Both strained supply chains and the sanctions cutting Russia off from global trade restricted supply. Contrary to what some opponents of sellers’ inflation will say, the theory does not deny the stimulus being inflationary (though some individual proponents might). Rather, sellers’ inflation is an explanation for the sustained inflation we saw over the past two years. Those shocks led to a mismatch between demand and supply for consumer goods, but something kept inflation high even after the effects of those shocks should have waned.

The culprit is corporate power. With such a whirlwind of economic shocks, consumers are less able to tell when prices are rising to offset increases in the cost of production versus when prices are being raised purely to boost profit. This, too, is not at odds with conventional macro wisdom. Every basic model of supply and demand tells us that when supply dwindles and demand soars, the price level will rise. Sellers’ inflation is an explanation of how and why prices rise and why prices will increase more in an economy with fewer firms and less competition.

Sellers’ inflation is really just a specific application of the theory of rent-seeking, which has been largely accepted since it was introduced by David Ricardo, a contemporary of the father of modern economics, Adam Smith. (Indeed, this point, which I raised nearly a year and a half ago in Common Dreams, was recently explored in a new paper from scholars at the University of London.) As anyone who has ever watched a crime show could tell you, when you want to solve a whodunnit, you need to look at motive, means, and opportunity. The greed (which, again, is at the same level it always is) is the motive. Corporations will always seek to charge as high of a price as they can without being dangerously undercut by competitors. Sellers’ inflation doesn’t posit a massive increase in corporate greed, but a unique economic environment that allows firms to act upon the greed they have possessed.

Concentration is the means; when the market is in the hands of only one or a few firms, it becomes easier to raise prices for a couple of reasons. First, large firms have price-setting power, meaning they control enough of the sector that they are able to at least partially set the going rate for what they sell. Second, when there’s only a few firms in a sector, wink-wink-nudge-nudge pricing coordination is much easier. Just throw in some vague but loaded phrases in press releases or earnings calls that you know your competition will read and see if they take the same tack. For simplicity, imagine an industry dominated by two firms, A and B. At any given point, both are choosing between holding prices steady and raising them (assume lowering prices is off the table because it’s unprofitable, let’s keep it simple.) This sets up the classic game-theoretical model of the prisoner’s dilemma:

| A Maintains Price | A Raises Price | |

| B Maintains Price | →, → | ↓, ↑ |

| B Raises Price | ↑, ↓ | ↑, ↑ |

In the chart above, the red arrows represent the change in A’s profit and the blue represent the change in B’s. If both hold the price steady, nothing changes, we’re at an equilibrium. If one and only one firm raises prices without the other, the price-hiker will lose money as price-conscious consumers switch to their competitor, who will now see higher profits. This makes the companies averse to raising prices on their own. But, if both raise their prices, both will be able to increase their profits. That’s why collusion happens. But, wait, isn’t that illegal? Yes, yes it is. But it is nigh on impossible to police implicit collusion, especially when there is a seemingly plausible alternative explanation for price hikes.

As James Galbraith wrote, in stable periods, firms prefer the safer equilibrium of holding prices relatively stable. As he explains: