Many have discussed and debated consumer welfare standard (“CWT”). The CWT is the normative economic standard based on Marshall’s consumer surplus theory that many advocate should guide antitrust policy and goal selection.

In our recent paper with Gabriel Lozada, we have categorized the problems with the consumer welfare theory into three general groups: (1) The theory is narrow because it eliminates traditional antitrust goals and populist antitrust goals a priori; (2) Its policy prescriptions are biased in favor of big business and the wealthy, and (3) It suffers from serious internal inconsistencies that have caused most welfare economists to abandon the approach. In this post, we summarize the first categorical problem with the CWT: Only factors that affect surplus matter.

Antitrust goals

According to CWT advocates, if something can’t be measured using economic surplus, it can’t be a goal of antitrust policy. When Judge Bork and other Chicago School advocates rebranded Alfred Marshall’s consumer surplus theory as the CWT, they were motivated by a desire to purge what they referred to as “value judgments” from antitrust policy. These “value judgments” were the traditional antitrust goals of promotion of political democracy and protection of small business that prominently appear in the legislative history of the antitrust statutes and have been recognized by many pre-Rehnquist Court Supreme Court opinions. As an example, Justice Warren wrote in Brown Shoe that “Congress was desirous of preventing the formation of further oligopolies with their attendant adverse effects upon local control of industry and upon small business.” Yet CWT advocates dismiss such concern.

Marshall’s theory served this purpose because it defined economic welfare as economic surplus, the difference between demand and price. Consumers have economic surplus, as does labor (the difference between the actual wage and the reservation wage), as do intermediate sellers. CWT advocates argue that if a policy goal can’t be measured using economic surplus, it is not “objective,” “scientific,” “economically viable,” or whatever methodological adjective they wish to use. Those arguments demonstrate that the choice of CWT advocates is a value-laden policy choice, not one founded in science.

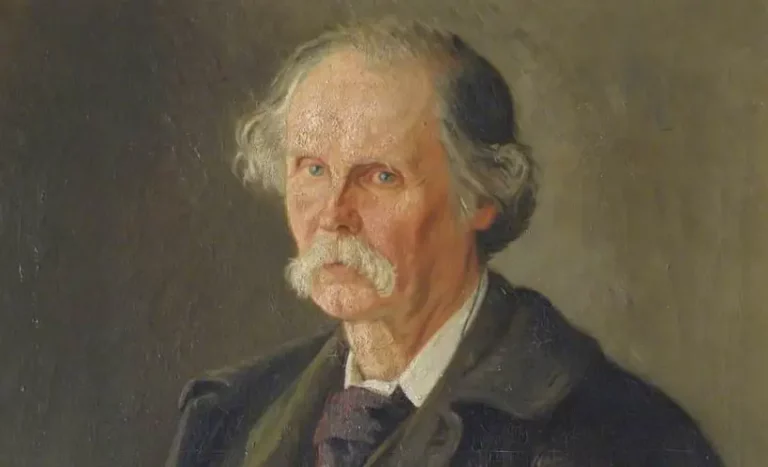

What would Marshall think?

The Chicago School application of Marshall’s theory is not supported by Marshall or modern welfare economics. Marshall himself recognized that welfare was much broader than economic welfare. Marshall and Pigou merely used the term “economic welfare” to distinguish the measurable aspect of total welfare using Marshall’s approach from the rest of total welfare. Indeed, neither economist ever advocated that only what was measurable was a proper goal for government policy. In his day, Marshall supported many policy initiatives that were not strictly measurable using the surplus approach.

Today, major programs initiated by welfare economists are measuring many aspects of welfare that are not directly captured by economic surplus, such as the impact of democracy, health, inequality, sustainability and others, and no welfare economists believe that welfare is limited to economic surplus or is captured by growth of output or GDP. For example, the U.N., the World Bank, the OECD, and many countries have initiated projects to better measure welfare.

There is no economic reason to discard the long standing traditional antitrust goal of dispersion of economic and political power. Stephen Martin has recently made this case. Both Senator Sherman and Senator Hoar, important drafters of the Sherman Act, expressed concern that monopolies would undermine democracy. Members of Congress repeated those concerns when they passed the Clayton Act and the FTC Act. Concerns about democracy were prominent in passage of the Celler-Kefauver Act. These concerns were echoed by Supreme Court Justices. Well, until relatively recently.

Research by welfare economists shows that democracy is a major factor in human well-being and quality of life. Bruno Frey summarizes the literature on democracy and well-being in his book Happiness: A Revolution in Economics, concluding that:

Overall, these results suggest that individuals living in countries with more extensive democratic institutions feel happier with their lives according to their own evaluation than individuals in more authoritarian countries. These results are not prompted by directly asking whether individuals would be happier living in a democracy. Rather, the subjective, self-reported evaluation of well-being has been gathered, independent of the objective political conditions. Moreover, many other influences on happiness are controlled for, and a certain amount of trust can therefore be placed in the results.

Political democracy was an originating Congressional goal. Political democracy matters for human welfare. Can competition policy impact political democracy? This seems likely given the importance of antitrust policy to media markets and high-tech ecosystems. Does it really make sense that because political democracy is not measured by economic surplus, it is not a “scientific” or “objective” goal? Not to us.

An indefensible standard

CWT isn’t a defensible standard, and its entrenchment bars discussion of more useful alternatives. The CWT approach of limiting antitrust goals to those that are measurable using the surplus approach to welfare (an approach deemed unreliable by most welfare economics) is simply not defensible. If competition policy can have a positive impact on a factor that has been shown to have major welfare implications, certainly Marshall’s 1890 theory should not be an impediment to addressing such a goal.

In sum, the CWT is not a tenable approach as an antitrust standard. It does not focus or advance reasonable debate on whether an antitrust goal should be adopted. It is merely a tool to a priori eliminate from the debate all but a very limited range of objectives, but without any principled reason for the limitation. The fact that it eliminated a priori the goals that motivated Congress to adopt the antitrust statutes in the first place should have been a sufficient red flag to render the CWT a non-starter as the foundation of antitrust policy.

Unfortunately, this was not the case.