Free trade is under increasing attack by both the progressive left and the populist right. Although the left and the right offer different policy solutions—the progressive left stresses combining industrial policy, antitrust policy, and support for labor with targeted tariffs, while the populist right advocates a wider use of tariffs combined with stricter immigration policy—supporters of both of these groups no longer adhere to the neoliberal free trade approach advocated by most economists. Are both of these voices misinformed about economics?

We argue that it is neoliberal economists who are wrong about the economics of trade. Economics textbooks and popular work by economists typically hide the unrealistic assumptions that are required to conclude that free trade as practiced by the United States is a beneficial policy overall, meaning that it is welfare-improving.

The Case for Free Trade: Comparative Advantage

The basis for the economic claim that free trade is beneficial is the early 19th century British political economist David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. The basic logic is that it is always more efficient for each party engaged in trade to specialize in what they do best. Per this logic, even if your spouse can earn more money than you can and they can perform better childcare, if you are better at childcare than at earning money, the childcare should be assigned to you. Likewise, if each nation specializes in what they do best, and then trades with other nations for other goods, everyone benefits.

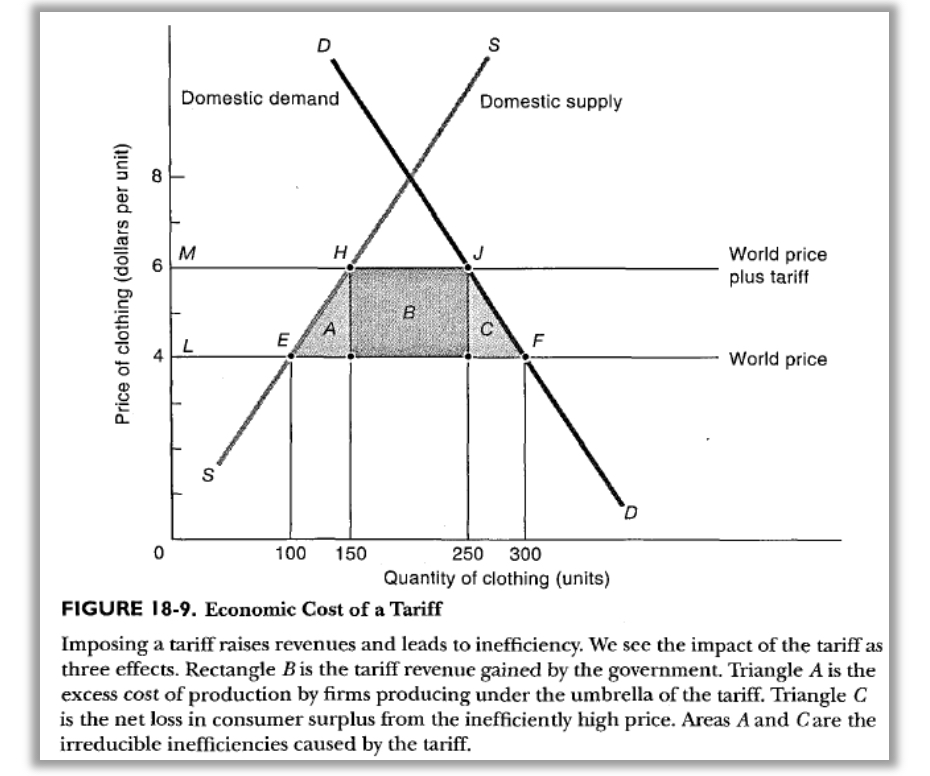

In the classic textbook treatment, the benefits of comparative advantage are expressed in diagrammatic form. For example, the famous textbook of Samuelson and Nordhaus (2010) uses the following graph to prove the loss in social surplus caused by tariffs.

In this graph, imposition of the tariff causes the domestic price level to rise from 4 to 6 (from the line to the line ). This price increase causes domestic consumption to fall from 300 to 250 units, which in turn causes consumer surplus to fall by area C. Interpret the “world price” horizontal line LF as the foreign supply curve and the foreign marginal cost curve, and interpret the “domestic supply” line SEHS as the domestic supply curve and the domestic marginal cost curve. The tariff causes domestic production to rise from 100 to 150 units, and area A is the increase in production costs caused by this shift from low-cost foreign producers to higher-cost domestic producers. The sum of A and C is the loss of social surplus caused by the tariff.

This demonstration has held great sway among economists. In covering the January 2025 meeting of the American Economic Association, the New York Times reported that “free trade is perhaps the closest thing to a universally held value among economists.” To back this up, the article cited a 2016 survey by the University of Chicago’s Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets of their panel of prominent academic economists from top universities, in which 39 out of 39 strongly disagreed or disagreed that “Adding new or higher import duties on products such as air conditioners, cars, and cookies—to encourage producers to make them in the U.S. —would be a good idea.” There was another survey performed by the Clark Center in 2018, in which 40 out of 40 of the panel disagreed that “Imposing new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans’ welfare.” For a more general question asked in 2012, “Free trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment,” the votes were 35 strongly agree or agree, two were uncertain, and none disagreed.

The economic argument depicted by the diagram is unassailable, but only if several unsurfaced assumptions hold. Although many economists highly value logical argument, they are at the same time remarkably tolerant of unrealistic assumptions of the sort we are about to discuss.

The Failed Assumptions of the Free Trade Model

There are five assumptions (two explicit and three implicit) needed to support the free-trade argument as depicted in the diagram above.

The first explicit assumption is that there is full employment in the domestic economy. It is assumed that when workers are displaced by imports, they can easily become re-employed at the same wages. If this is not the case, then removal of a tariff causes a loss of social surplus (a loss of economic rent) in the domestic labor market, which the analysis based on the above figure misses because it only depicts the output market.

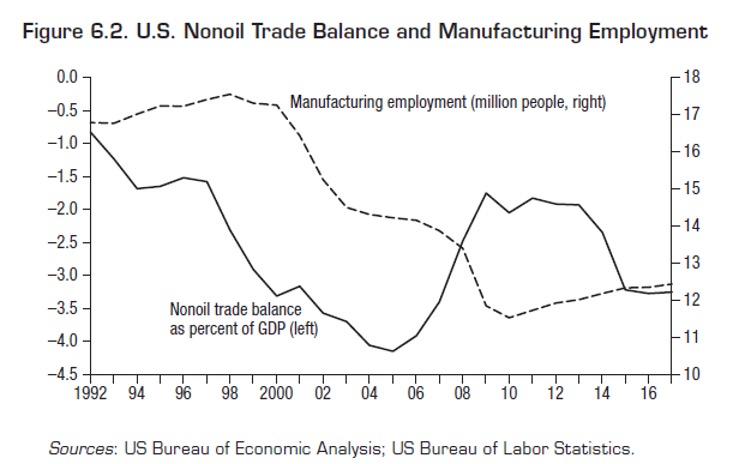

Yet the assumption of full employment does not hold empirically. On the contrary, here is a revealing graph from an article by Paul Krugman (2019).

Trade job loss has been 74 percent in manufacturing, which is one of the few sectors where non-college-degree-holding males could earn a good living. Contrary to free trade theory, the U.S. lost jobs, primarily in high tech, computer parts, electronics, and durable goods manufacturing. Between 2001 and 2018, EPI estimates that the U.S. lost 1,132,500 jobs to Chinese imports but only gained 175,800 jobs to exporting industries to China.

In their work on the China Syndrome, Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013) show that the impact on labor comes “less from its economy-wide impacts than from its disruptive effects on particular regions.” These disruptions would not have occurred if full employment, and frictionless re-employment, characterized the economy.

The second explicit assumption that undergirds the free trade theory is that there are no externalities. Pisano and Shih (2012) analyze the total impact of the loss of manufacturing jobs in particular regions. The impact can be enormous, stretching far beyond a manufacturing plant. Entire towns or cities can be hollowed out. A plant closure can destroy numerous small businesses, the tax base, and many complementary businesses. In addition, workers in the nontraded sector are hurt by an increased labor supply, and their bargaining power is undermined. None of these changes in social surplus are captured in the Samuelson and Nordhaus figure above.

Besides these two explicit assumptions, policy analysts who advocate free trade often make three more implicit assumptions, as enumerated by Fletcher (2011). These are also flawed.

The first implicit assumption is that comparative advantage results in short-run efficiencies that cause long term growth and development. The problem with this idea in practice is that comparative advantage is a static theory. The inside joke among economists is that each country should do what it is best at doing, and what underdeveloped countries are best at is underdevelopment.

The evidence is strongly contrary to this assumption. Indeed, no country has successfully developed under free trade. In his book Kicking Away the Ladder, Ha-Joon Chang reviews the development history of every developed country and shows that every one of them used significant tariffs as part of its development strategy. Joe Studwell, in How Asia Works, shows that all of the Asian Tiger countries used trade protection with government industrial policy to develop. So free trade is not a development strategy. It is a static policy that can impede development.

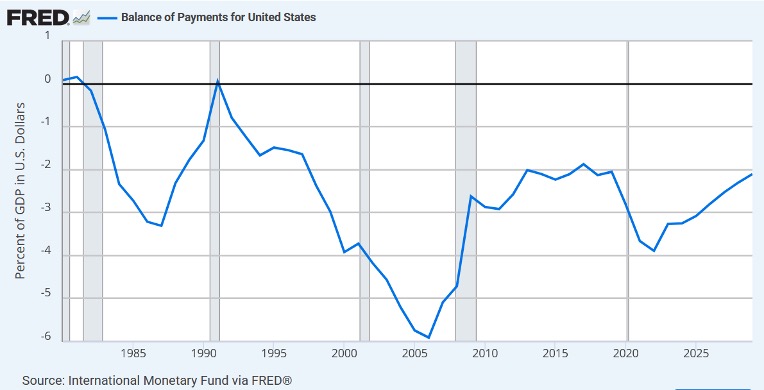

The second implicit assumption that undergirds free trade theory is that freely-floating currencies will keep trade balanced, limiting imports and ensuring that benefits exceed loses. This is not true, as trade with the U.S. has not been balanced for many decades per the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

After the U.S. liberalized capital markets in the 1980s, trade deficits were supported by capital movements into the United States. Foreigners have used their dollars to purchase U.S. securities and real estate, which does not increase U.S. productivity because it generates no new capital formation (at least directly).

The third implicit assumption is that the U.S. provides adequate compensation for job losses caused by international trade. On the contrary, Lori Kletzer (2001) analyzed the U.S. policy response to trade-induced job losses and found it to be woefully inadequate. By contrast, countries that have strong labor support policies (like strong social safety nets) are generally much better able to garner the benefit from international trade without suffering social and political costs from it.

In the absence of these five assumptions, the free trade argument is completely undermined.

And if these five weren’t enough, there is another, more basic assumption underlying the free trade argument that needs to be debunked—namely, the assumption that social surplus areas of the sort used in the graphic presentation of the free trade argument are a correct measure of welfare. For more on that, see our papers with Darren Bush.

Our position is not that free trade is never the correct policy. Comparative advantage exists; even permanent comparative advantage exists. But analysis of free trade policies should occur in a real-world framework, not one that makes important assumptions which do not hold, even approximately, in the real world.