Last week, I had the honor of presenting a paper, co-authored with Jacob Linger and Ted Tatos, on the causes of rental inflation to competition authorities from around the world at the OECD competition conference in Paris. Many factors contribute to rising rents, but one factor hasn’t received much attention: the consolidation of properties by developers within neighborhoods. I’m hoping to change that.

Softening the Beachheads

Before telling you my theory on the nexus between competition and inflation, let me say what it is not: It is not that concentration changed suddenly in 2021, causing an uptick in prices. That’s a straw man invented by Larry Summers and other members of his neoliberal cabal. The real nexus rests with the ability of market concentration to facilitate price coordination, and a small bout of inflation can grease the skids even further.

In December 2021, I was in a courtroom in San Francisco watching a videotape of a Japanese executive whose company was embroiled in a price-fixing conspiracy. And the CEO told the jury that his cartel functioned most efficiently during times of inflation. I nearly fell out of my wooden bench.

He offered two theories, which I have translated into Economese. The first is what I call “Softening the Beachheads,” an unfortunate war analogy. Consumer resistance to price hikes may soften with inflation because there is now a pretext for the price increase. The second is what economists will recognize as a “focal point”—inflation solves coordination problem by providing a floor for future price increases.

Notice that neither theory requires any increase in concentration. The driving force lies with the interaction of inflation with the existing high level of concentration, exacerbated by existing coordination among firms.

The Rental Inflation Problem

Although general inflation began to fall below nine percent in the United States in August 2022, the CPI for “Shelter,” comprised of “Rent of primary residencies” plus “Owners equivalent rents of residences,” continued rising, reaching levels above nine percent. Shelter contributes 32 percent to the total CPI and about 40 percent of core inflation. With the exception of the onset of Covid, housing inflation has generally tracked overall inflation. In 2022, rents were up almost 15 percent in the Miami/Atlanta metro area and by 21 percent in Phoenix. Per Zillow research, renters face growing housing affordability hurdles in the United States; renters in Miami, for example, need to work 96 hours at the average wage to pay the typical rent.

Given its outsized importance, if we could solve the rental inflation problem, we could go a long way to solving the problem of inflation generally. To use a simple analogy, if there was a fire alarm going off in your house, you would want to know the source. Is it coming from upstairs? And once you know the room, you might be able to put out the fire there. You wouldn’t want to apply some generalized treatment, like bulldozing the house.

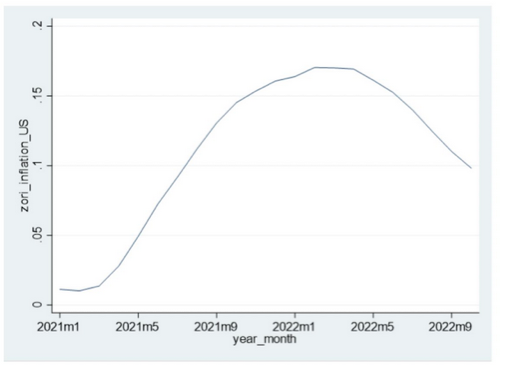

Some might mistakenly consider the story of rental inflation to be in the rear-view mirror because the Zillow Observed Rental Index (ZORI) has been falling in the last half of 2022.

National ZORI Index (Percentage Change from Last 12 Months)

As the figure shows, even by October 2022, the ZORI was still above ten percent, which exceeds the general CPI. More importantly, because the ZORI is a measure of asking rents, the index will display a more pronounced inflation decline compared to the average rents across all rented units, including those already paying rents at prior agreed-upon rates. In other words, we’re not out of the woods.

Economists Have Their Stories

Economists offer myriad competing narratives. The neoliberal crowd tends to look for stories that absolve the companies actually setting prices. Krugman speculates that the demand for remote working from home, initiated by Covid, caused consumers to demand larger household footprints. This isn’t a very a compelling hypothesis, as it wouldn’t explain across-the-board rental inflation, including on smaller, one-bedroom units. A Redfin economist blames migration from the Coastal cities to the Sun Belt, again initiated by Covid. Again, not entirely persuasive, as it fails it to explain rising rents outside the Sun Belt. And the business press, including the speciously liberal New York Times, harps on the claim that higher prices, including for rents, are caused by higher costs; never mind the marginal cost of leasing the last unit of a multi-family residence is close to zero.

Or maybe, just maybe, the companies setting rents are to blame. I realize this is novel stuff, particularly among economists conditioned to reflexively defend market outcomes as efficient regardless of the mechanism behind them. In ten U.S. cities, including Atlanta, Jacksonville, Tampa and Orlando, institutional investors, defined as entities owning over 100 properties nationwide, had previously acquired at least 15 percent of all single-family rental units. This suggests a possible nexus between concentration (in levels) and rental inflation.

Proving the Nexus

We are not the first to examine the nexus between rental pricing and concentration. If you read our paper, you can learn about these studies in our literature review. I’ll call your attention to just one—a Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis paper finding a connection between institution ownership and rent to income ratios in a metropolitan statistical area. They find that purchases by institutional investors, as measured by the share of properties owned by all institutional investors collectively in a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), increase (1) the price-to-income ratio, especially in the bottom price-tier, the entry point for first-time buyers, and (2) the rent-to-income ratio generally, especially where the housing supply elasticity is high. By treating all institutional investors in the aggregate and thus as if it were owned a single entity, however, the St. Louis Fed study may have overlooked the incremental explanatory power of clustering properties by a single institutional owner in a given neighborhood. Put differently, an MSA with (say) ten percent institutional ownership, split equally across ten owners, could exhibit different pricing dynamics than an MSA with ten percent institutional ownership split equally across just two owners.

To address this evidentiary gap, we used Florida property tax roll data to construct the footprint of property owners in each neighborhood or census tract. We did this for two separate market distinctions: (1) All non-owner-occupied housing properties, and (2) all multifamily properties. This is an animated map of the South Shore neighborhood of River View from 2015 to 222. You can see how these five owners have built up a cluster of properties over time. And that cluster gives them pricing power, both unilaterally and collectively.

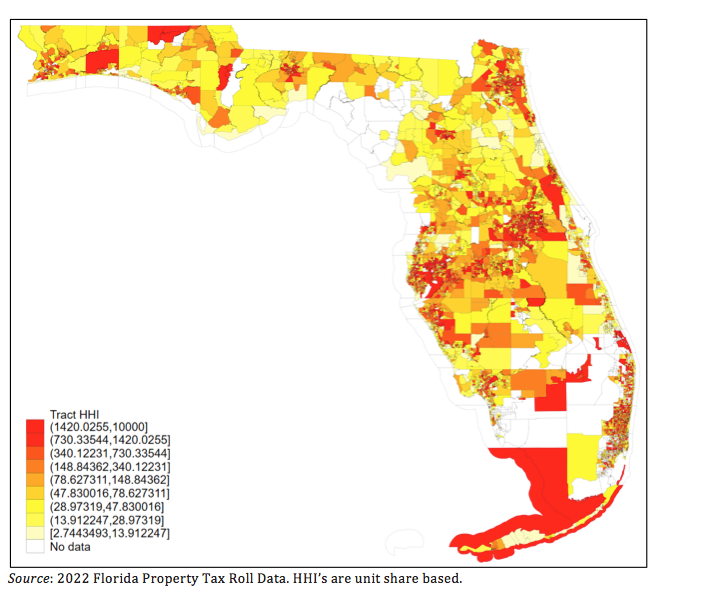

We calculate the Herfindahl Hirschman Index (HHI) among property owners in a given Census Tract as the primary explanatory variable of interest. This approach assumes that the Census Tract approximates the area over which renters perceive rental units to act as reasonably close economic substitutes (or in antitrust parlance, a relevant geographic market). We believe this is the case as renters choose where to live based on neighborhood attributes, and neighborhoods can exhibit wide variation within a specific county or city. Yet there is not a consistent geographic mapping of neighborhoods within the social sciences, and Census tracts are often instead used as a proxy. For each of these markets, we estimate the tract-level HHI by summing the squared unit market share values within the tract. The figure below presents a map of tract-level HHIs in 2022 based on unit shares of non-owner-occupied housing properties. Lower HHI areas are colored lighter yellow, while higher HHIs areas appear in dark red. We lacked ownership data for those areas that appear whited out.

Florida Census Tract HHIs in 2022

Source: 2022 Florida Property Tax Roll Data. HHI’s are unit share based.

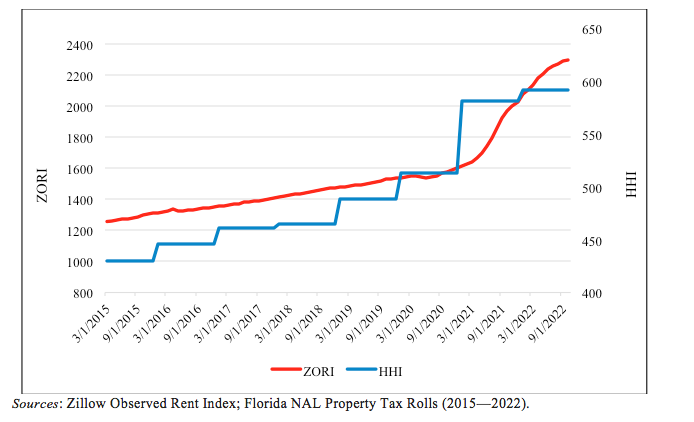

For rents, we utilized the Zillow Observed Rent Index (ZORI), which indexes the mean of the middle 30% of asking rents by month. The figure below plots the relationship between our measures of rents and rental ownership across time for all non-owner-occupied rental markets. Both rents and concentration levels have seen a steady uptick, with an increasing inflationary trend over the last two years.

Florida Monthly Average ZORI and HHI by Census Tract (2015—2022)

Sources: Zillow Observed Rent Index; Florida NAL Property Tax Rolls (2015—2022).

You can see how the ZORI seems to track the average HHI across all Florida neighborhoods. To be fair, this relationship would not explain rental inflation, but instead would suggest that higher concentration is associated with higher rents. There does appear to be a jump, however, in the average HHI at the beginning of 2021, which could be an inflation story—though not the one we’re telling.

To investigate this relationship further, we build a regression model that sought to relate concentration with both rent levels and rental inflation, controlling for other things that drive rents, such as migration. I’ll leave it to the reader to go check out our results. (And for the R-squared nuts on Twitter, you’ll have to come up with a better rejoinder this time!) Our main findings are that both rent and rental inflation in Florida are statistically and economically significantly correlated with the level of concentration within a neighborhood or census tract.

Surrendering to the Chicago School

We are keenly aware of the controversy in industrial organization of using HHI as an explanatory variable in a price regression. (Not much has been written on inflation regressions, but we expect the same critique.) We think the lesson from Whinston and other pioneers in this area is to look for instruments or proxies for HHI, rather than abandoning the exercise altogether. Indeed, we think it was a colossal mistake of liberal economists to offer this concession to Demsetz and the Chicago School, which was set on undermining the structural presumption. And indeed they won and antitrust enforcement was largely feckless over the last 40 years. If you want to learn about our instruments, and how they withstand various tests, you can read the paper.

With regard to policy implications, raising interest rates puts home ownership out of reach of millions of families, driving them to the rental markets, which bids up rental rates, which is one of the primary drivers of inflation. Let that sink in! Our results suggest a different course for arresting rental inflation—namely, for cities or states (or both) to impose an ownership limit on the amount properties an individual owner could control in a given neighborhood. Antitrust enforcement could serve as a check against inflation over the long term, to the extent it is used to fight concentration in rental markets and through the economy writ large; but given antitrust’s glacial pace, the best course now for arresting rental inflation requires going outside of antitrust.