On Wednesday, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) provisionally concluded that Microsoft’s proposed acquisition of Activision could result in higher prices, fewer choices, or less innovation for UK gamers. It also released a set of proposed remedies to address the likely anticompetitive harms, including a mandatory divestiture of (1) Activision’s business associated with its popular Call of Duty franchise; (2) the entirety of the Activision segment; or (3) the entirety of both the Activision segment and the Blizzard segment, which would also cover the World of Warcraft franchise.

Assuming Microsoft won’t go for any structural remedy, the deal is likely on ice, and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) would not have to bring any enforcement action against Microsoft. Although this is likely the right outcome from a competition perspective, the antitrust geeks (myself included) will suffer dearly from not getting to observe the theatrics around a hearing and the associated written decisions.

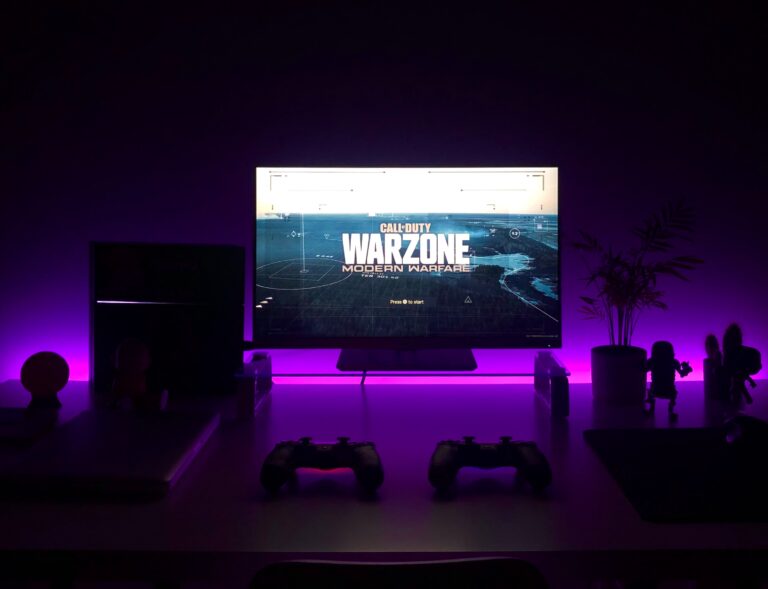

Setting aside Microsoft’s significant holdings in gaming studios, Microsoft’s attempted purchase of Activision can be understood as a vertical merger, in the sense that Microsoft sells its Xbox gaming platform (the downstream division) to consumers, in competition against Sony’s PlayStation and Nintendo’s Switch—and Activision supplies compelling games (the upstream division) for the various gaming platforms. The Xbox platform can be understood either as Microsoft’s traditional gaming console or as its nascent cloud-based Xbox Game Pass platform.

Challenges of vertical mergers have not been successful of late, prompting many scholars to call for new vertical merger guidelines. Among the suggested remedies would be a “dominant platform presumption,” advocated by antitrust law professor Steve Salop, which would shift the burden of proof to the acquiring firm whenever it was deemed a dominant platform.

It’s All About the Departure Rate

Input foreclosure is the term used by economists to describe how a vertically integrated firm—think post-merger Microsoft—might withhold a key input from distribution rivals, thereby impairing the rivals’ ability to compete for customers. When the theory of harm is input foreclosure, proof of anticompetitive effects largely turns on how special or “must-have” the potentially withheld input is for downstream rivals. Economists define the “departure rate” as the share of the rival’s customers who would defect if they could not access the withheld input. Under these models, anticompetitive effects also require that the downstream firm possess a significant market share.

In the Justice Department’s attempt to block AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner in 2018, the agency’s economic expert leaned on an estimated departure rate generated by a third-party consultant. That third-party consultant originally produced results consistent with a low departure rate, suggesting that losing CNN would not cause too much customer defection, only to be changed to a high departure rate before being handed to the economic expert for incorporation into his work. Regardless of how the work was performed, it strained credulity that CNN was considered a must-have input by cable distribution rivals and their customers. Moreover, AT&T’s (local) share of the distribution market, even in its limited footprint, was not substantial.

In contrast, Microsoft wields a commanding share of gaming platforms, by some estimates as high as 60 to 70 percent of global cloud gaming, but only 25 percent of gaming consoles per Ampere Analytics. Call of Duty is considered a must-have input among gaming platforms, based in part on CMA’s analysis of internal “data on how Microsoft measures the value of customers in the ordinary course of business.” For modeling purposes, it still would be incumbent on the agency’s economist to measure the departure rate, and here it might be difficult to find a natural experiment—for example, where a platform temporarily lost access to Call of Duty—to exploit. As part of its investigation, CMA “commission[ed] an independent survey of UK gamers,” which could have been used to asked Call of Duty users whether they might leave a platform if they couldn’t access their favorite game. CMA noted that Microsoft has already employed a strategy “of buying gaming studios and making their content exclusive to Microsoft’s platforms … following several previous acquisitions of games studios.”

Microsoft has made commitments to Sony and Nintendo to continue releasing its new Call of Duty games for ten years. Yet such commitments are hard to enforce, and could be undermined through trickery. For example, Microsoft could offer access only at some unreasonable price, or only under unreasonable conditions in which (say) the rival platform also agreed to purchase a set of boring games, alongside Call of Duty, at a supracompetitive price. Without a regulator to oversee access, the commitment could be ephemeral, much like T-Mobile’s access commitment to Dish, to remedy T-Mobile’s acquisition of Sprint, which is widely recognized as a farce. Despite its disfavor of behavioral remedies, CMA noted in its notice of possible remedies that it would nevertheless “consider a behavioural access remedy as a possible remedy,” yet concludes that the agency is “of the initial view that any behavioural remedy in this case is likely to present material effectiveness risks.”

Microsoft reportedly entered into a neutrality agreement with organized labor, under which Microsoft would not impair progress towards unionization of Activision employees. Whatever benefits such an agreement might generate for workers, those benefits could not be used to offset the harms suffered by consumers in the product markets under Philadelphia National Bank. Unfortunately, the treatment of offsets is not as clear under monopolization law.

What Goes Around Comes Around

If CMA’s actions ultimately stop the Microsoft-Activision merger, the relatively weaker merger enforcement in the United States would get a pass. U.S. antitrust agencies are readying a revised and more stringent set of merger guidelines, which would bring U.S. standards in line with European authorities. In the meantime, the global reach of the dominant tech platforms—and thus exposure to foreign antitrust regimes—might ironically protect U.S. consumers from the platforms’ most audacious lockups.