This piece originally appeared in ProMarket but was subsequently retracted, with the following blurb (agreed-upon language between ProMarket’s Luigi Zingales and the authors):

“ProMarket published the article “The Antitrust Output Goal Cannot Measure Welfare.” The main claim of the article was that “a shift out in a production possibility frontier does not necessarily increase welfare, as assessed by a social welfare function.” The published version was unclear on whether the theorem contained in the article was a statement about an equilibrium outcome or a mere existence claim, regardless of the possibility that this outcome might occur in equilibrium. When we asked the authors to clarify, they stated that their claim regarded only the existence of such points, not their occurrence in equilibrium. After this clarification, ProMarket decided that the article was uninteresting and withdrew its publication.”

The source of the complaint that caused the retraction was, according to Zingales, a ProMarket Advisory Board member. The authors had no contact with that person, nor do we know who it is. We would have welcomed published scholarly debate versus retraction compelled by an anonymous Board Member.

We reproduce the piece in its entirety here. In addition, we provide our proposed revision to the piece, which we wrote to clear up the confusion that it was claimed was created by the first piece. We will let our readers be the judge of the piece’s interest. Of course, if you have any criticisms, we welcome professional scholarly debate.

(By the way, given that the piece never mentions supply or demand or prices, it is a mystery to us why any competent economist could have thought it was about “equilibrium.” But perhaps “equilibrium” was a pretext for removing the article for other reasons.)

The Antitrust Output Goal Cannot Measure Welfare (ORIGINAL POST)

Many antitrust scholars and practitioners use output to measure welfare. Darren Bush, Gabriel A. Lozada, and Mark Glick write that this association fails on theoretical grounds and that ideas of welfare require a much more sophisticated understanding.

By Darren Bush, Gabriel A. Lozada, and Mark Glick

Debate seems to have pivoted in the discourse on consumer welfare theory to the question of whether welfare can be indirectly measured based upon output. The tamest of these claims is not that output measures welfare, but that generally, output increases are associated with increases in economic welfare.

This claim, even at its tamest, is false. For one, welfare depends on more than just output, and increasing output may detrimentally affect some of the other factors which welfare depends on. For example, increasing output may cause working conditions to deteriorate; may cause competing firms to close, resulting in increased unemployment, regional deindustrialization, and fewer avenues for small business formation; may increase pollution; may increase the political power of the growing firm, resulting in more public policy controversies and, yes, more lawsuits being decided in its interest; and may adversely affect suppliers.

Even if we completely ignore those realities, it is still possible for an increase in output to reduce welfare. These two short proofs show that even in the complete absence of these other effects—that is, even if we assume that people obtain welfare exclusively by receiving commodities, which they always want more of—increasing output may reduce welfare.

We will first prove that it is possible for an increase in output to reduce welfare under the assumption that welfare is assessed by a social planner. Then we will prove it assuming no social planner, so that welfare is assessed strictly via individuals’ utility levels.

The Social Planner Proof

Here we show that a shift out in a production possibility frontier does not necessarily increase welfare, as assessed by a social welfare function.

Suppose in the figure below that the original production possibility frontier is PPF0 and

the new production possibility frontier is PPF1. Let USWF be the original level of social welfare, so that the curve in the diagram labeled USWF is the social indifference curve when the technology is represented by PPF0. This implies that when the technology is at PPF0, society chooses the socially optimal point, I, on PPF0. Next, suppose there is an increase in potential output, to PPF1. If society moves to a point on PPF1 which is above and to the left of point A, or is below and to the right of point B, then society will be worse off on PPF1 than it was on PPF0. Even though output increased, depending on the social indifference curve and the composition of the new output, there can be lower social welfare.

The Individual Utility Proof

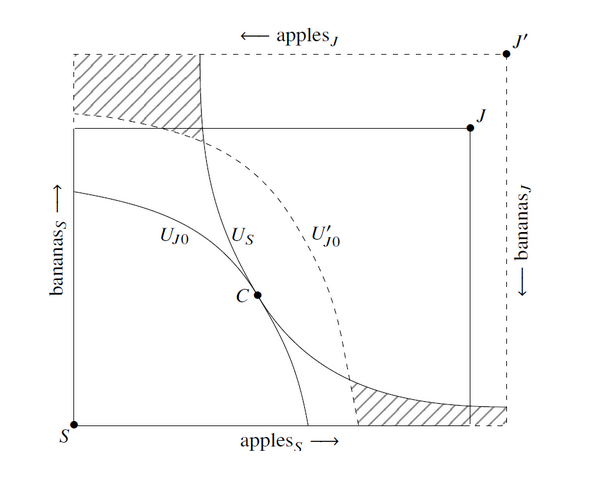

Next, we continue to assume that only consumption of commodities determines welfare, and we show that when output increases every individual can be worse off. Consider the figure below, which represents an initial Edgeworth Box having solid borders, and a new, expanded Edgeworth Box, with dashed borders. The expanded Edgeworth Box represents an increase in output for both apples and bananas, the two goods in this economy.

The original, smaller Edgeworth Box has an origin for Jones labeled J and an origin for Smith labeled S. In this smaller Edgeworth Box, suppose the initial position is at C. The indifference curve UJ0 represents Jones’s initial level of utility with the smaller Edgeworth Box, and the indifference curve US represents Smith’s initial level of utility with the smaller Box. In the larger Edgeworth Box, Jones’s origin shifts from J to J’, and his UJ0 indifference curve correspondingly shifts to UJ0′. Smiths’ US indifference curve does not shift. The hatched areas in the graph are all the allocations in the bigger Edgeworth Box which are worse for both Smith and Jones compared to the original allocation in the smaller Edgeworth Box.

In other words, despite the fact that output has increased, if the new allocation is in the hatched area, then Smith and Jones both prefer the world where output is lower. We get this result because welfare is affected by allocation and distribution as well as by the sheer amount of output, and more output, if mis-allocated or poorly distributed, can decrease welfare.

GDP also does not measure aggregate Welfare

The argument that “output” alone measures welfare sometimes refers not to literal output, as in the two examples above, but to a reified notion of “output.” A good example is GDP. GDP is the aggregated monetary value of all final goods and services, weighted using current prices. Welfare economists, beginning with Richard Easterlin, have understood that GDP does not accurately measure economic well-being. Since prices are used for the aggregation, GDP incorporates the effects of income distribution, but in a way which hides this dependence, making GDP seem value-free although it is not. In addition, using GDP as a measure of welfare deliberately ignores many important welfare effects while only taking into account output. As Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy put it:

GDP takes a positive count of the cars we produce but does not account for the emissions they generate; it adds the value of the sugar-laced beverages we sell but fails to subtract the health problems they cause; it includes the value of building new cities but does not discount for the vital forests they replace. As Robert Kennedy put it in his famous election speech in 1968, “it [GDP] measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

Any industry-specific measure of price-weighted “output” or firm-specific measure of price-weighted “output” is similarly flawed.

For these reasons, few, if any, welfare economists would today use GNP alone to assess a nation’s welfare, preferring instead to use a collection of “social indicators.”

Conclusion

Output should not be the sole criterion for antitrust policy. We can do a better job of using competition policy to increase human welfare without this dogma. In this article, we showed that we cannot be certain that output increases welfare even in a purely hypothetical world where welfare depends solely on the output of commodities. In the real world, where welfare depends on a multitude of factors besides output—many of which can be addressed by competition policy—the case against a unilateral output goal is much stronger.

Addendum

The Original Sling posting inadvertently left off the two proposed graphs that we drew as we sought to remedy the Anonymous Board Member’s confusion about “equilibrium.” We now add the graphs we proposed. The explanation of the graphs was similar, and the discussion of GNP was identical to the original version.

The Proof if there is a Social Welfare Function (Revised Graph)

The Individual Utility Proof (Revised Graph)