These past few months have had more than their share of decade-long weeks. Not even three months in, the second Trump administration has already totally shattered norms and scrambled the playing field, challenging everything we thought we knew about the government’s role in the economy. We thought that Congress had the power of the purse, but now that’s become a question seeking an answer. We thought that even the president had to follow instructions from the courts, but now everyone is left to wonder if that is still the case. Once sacred norms atrophy daily.

Yet one thing the Trump administration has cast into doubt that gets little air time is the usefulness of neoclassical economic theory in explaining the economy.

The classical school of economics generally describes the theory of the first cohort of economists in our modern understanding of the discipline—though it was still radically different from the modern iteration, much more intertwined with studies of politics and philosophy. Most famous among these early economists is Adam Smith himself. Other notable figures include David Ricardo, Thomas Robert Malthus, James Mill, and James’ (more well-known) son John Stuart Mill. Most of modern economic theory descends from this small group of English and Scottish political economists.

It bears mentioning that this is not because classical economists were the first to rigorously investigate the economy, but rather because they crystallized it into a concrete area of study, whereas previously it was considered part of moral philosophy and political philosophy and history and in the study of the classics and on and on. Indeed, most of the classical economists were also philosophers—the key concept of utilitarianism is a philosophical foundation of most economic thought.

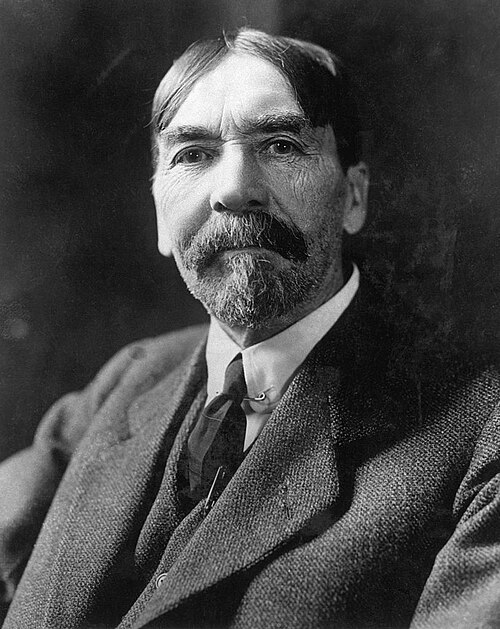

The neoclassical school, on the other hand, was a category originally used by Thorstein Veblen to group the Austrian school of thought with the “marginalists,” whose work centered around the insights to be gained by examining effects at the, you guessed it, margins. The term was later adopted and expanded by other economists.

Over the course of the twentieth century, much of the original canon of Austrian economics, and a number of significant theoretical advancements like F.A. Hayek’s theory of prices as purveyors of information, were absorbed into the mainstream. At the same time, the demand-side economic theory of John Maynard Keynes became so accepted that—from World War II through the dawn of Reaganomics—a common refrain was that “we are all Keynesians now.” This synthesis left “neoclassical economics” as a stand-in for all of the core ideas of the discipline.

Nowadays, neoclassical economics is usually used simply to mean “mainstream” or “orthodox” economics, as opposed to heterodox schools of thought like institutional economics (of which Veblen is often considered a founder), Marxian or Marxist economics, or Modern Monetary Theory. Although it is arguably too broad of a term to be of much use, there are enough basic intellectual throughlines that we can at least gesture at a “neoclassical” school of thought.

Neoclassical economics models and theories are premised on a handful of key assumptions. They will vary slightly depending on who exactly you ask, but generally include:

- Economic actors (usually meaning either people or firms) make rational decisions to optimize an objective.

- Individuals seek to maximize their utility, within the constraints of their situations. Firms seek to maximize their profit, subject to the bounds of their constraints.

- Each actor makes decisions independently.

- Everyone involved has full information about the economic interaction.

These assumptions are obviously not universally true and most economists don’t believe them to be. Rather, the idea is that by reducing complexity, one can discern how various changes to a model will shift behavior, economic interactions, and, ultimately, the dynamics of a market. And once that’s done, those same general dynamics should approximate the more complicated real world.

This has always been somewhat dubious and has never been short of critics—the modern Austrian school is partly a heterodox tradition because they were opposed to these formal, more mathematical models. Indeed, most cutting-edge mainstream economics is about relaxing neoclassical assumptions to create a richer picture that better captures human behavior. More so than actual professional economists, reporters and media personalities have embraced oversimplified models as a crutch for economic analysis. For instance, when opposing some modest intervention into a market, the talking heads insist on discussing the “Econ 101” (read: obvious) view.

The irony is that the discipline itself understands the limited use of such simplistic concepts. Econ 101 introduces concepts that are increasingly complexified in further study. Because reporters and talking heads usually didn’t study advanced economics, much of the discourse winds up being unscrupulously grounded in the handful of assumptions outlined above. Nothing has shattered the illusion that we can understand complex situations with basic models like the start of the second Trump administration.

Shaking the Foundations

Trump’s recent implementation and then partial rollback of tariffs is a good case study. Despite being a cornerstone of the president’s 2024 campaign, business leaders were reportedly surprised at the size and scope of Trump’s initial proffer. And investors clearly did not price such a dramatic intervention in trade policy into their expectations, as evidenced by the rapid gyrations of the stock market. It makes sense when you consider that political and business insiders often default to explaining decisionmaking via presumed rationality. The orthodox view was basically that this kind of sweeping and incoherent tariffs wouldn’t happen; because the costs so outweighed the benefits, such an intervention would clearly go against the government’s (ergo the president’s) basic self-interest. (An example of this sort of thinking beyond economics is political science’s rational state theory—a consequence of how neoclassical economics has colonized much of political science.)

Even though the tariffs have quickly been walked back—even if in the coming days, weeks, or months they are totally undone—the key issue is that, under a neoclassical framework, they would not have happened at all.

Now, one could retort that the market reacted exactly as even the most elementary model would predict; uncertainty made the prospects of financial markets less palatable, resulting in a scramble from investors to reduce their risk exposure, triggering a loss in valuation as the demand curve shifted down. True enough. But the fact that this played out so predictably is partially the point. Everyone knew that it would be economically harmful to impose blanket tariffs. It would obviously be antithetical to American financial interests. Yet the administration did it anyway.

There are basically two ways to reconcile the tariffs with a neoclassical model. First, the model could simply do away with the assumption of rationality. This would make it basically impossible, however, to use as a predictive tool (behavior would become too complex to easily anticipate). Second, the model could do away with the assumption that actors (governments, individuals) are optimizing for utility. Perhaps the White House is actually optimizing for profits for aligned businesses or for accumulating political influence. This type of tweaking of the “objective function,” is much more in line with existing economics, but still represents a major break from neoclassical models.

(The fact that this sort of work is ongoing and most economists do not actually adhere to such restrictive assumptions is one good reason why “neoclassical” being used interchangeably with “modern” or “orthodox” can be confusing. Unfortunately, many pundits, journalists, and businesspeople don’t study the discipline far enough to move beyond the oversimplified worldview.)

For the administration to take an action so clearly against the nation’s interest without breaking these assumptions, it would require believing that they have information that drastically changes the calculus. Possible, but unlikely when it comes to trade, where there’s little information opacity compared to, say, intelligence and national security.

Speaking of information, the current administration has scrubbed enormous amounts of data from federal government websites and databases (some data have been made available again after litigation and public pressure). Everything from omitting the role of trans people in Stonewall to removing reams of medical data has happened at a rapid pace. Some of this information may not be immediately relevant to economic decision-making. Other times the path from that data to economic or commercial relevance is a straight line. New pharmaceutical undertakings will suffer a material harm to their research and development with fewer resources from the National Institutes of Health. The poultry industry might well miss CDC data on avian flu.

But even beyond these specific applications, the withdrawal of mass amounts of previously public data fundamentally erodes the idea that economic actors will ever have anything resembling information symmetry. Not to mention how much widespread attacks on the media compound the issue.

One final issue is regulatory uncertainty. Rational, independent decision-making requires some degree of confidence in the laws and institutions governing the market you participate in. The pushing of novel legal theories—including that oral orders from judges are not binding or that the executive branch can eviscerate congressionally mandated departments and programs—makes it nearly impossible to presume that you can accurately predict the benefits or costs of any particular decision. When even gargantuan law firms prefer deference over self-defense, confidence in the rule of law no longer grants the basic trust required in a modern, global economy.

Goodbye to the Neoclassical World

One could argue that the weakening of these norms has nothing to do with economic thought, and that it’s just dirty politics. But markets are political. Institutions create rules governing behavior, including economic behavior. And a stable set of rules is necessary for any of the assumptions undergirding neoclassical models to play out.

To the extent that we ever lived in a neoclassical world, the Trump administration is ensuring that we don’t any longer. We are long overdue for more nuanced economic discourse that doesn’t shy away from its own limitations, and that recognizes when it can and should (perhaps must) be complemented with other types of insights. As the illusion of perfect competition becomes ever more ethereal, the need for more sophisticated economic thinking and debate becomes ever more urgent.